There are a whole bunch of different ways to create 3D scans of objects these days. Researchers at the [UW Graphics Lab] have demonstrated how to use a small, cheap time-of-flight sensor to generate scans effectively.

The key is in how time-of-flight sensors work. They shoot out a distinct pulse of light, and then determine how long that pulse takes to bounce back. This allows them to perform a simple ranging calculation to determine how far they are from a surface or object.

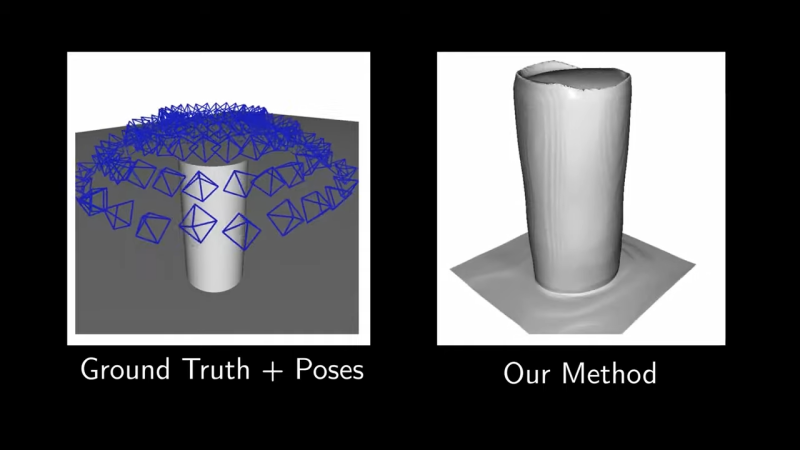

However, in truth, these sensors aren’t measuring distance to a single point. They’re measuring the intensity of the received return pulse over time, called the “transient histogram”, and then processing it. If you use the full mathematical information in the histogram, rather than just the range figures, it’s possible to recreate 3D geometry as seen by the sensor, through the use of some neat mathematics and a neural network. It’s all explained in great detail in the research paper.

The technique isn’t perfect; there are some inconsistencies with what it captures and the true geometry of the objects its looking at. Still, the technique is young, and more work could refine its outputs further.

If you don’t mind getting messy, there are other neat scanning techniques out there—like using a camera and some milk.

I may be speaking out of my ass here but isn’t this a strictly DSP problem? I don’t see any point in including neural networks but then again, I’m not familiar with this.

I also have a Pavlovian response to “AI” at this point, but there is a good reason for neural networks here.

The returned signal is a direct measurement of the scene, but there are many possible scenes that will give the same return. For instance, if you see a peak corresponding to a distance of 120cm, that can only be caused by objects 120cm away, but it could be a single object on the right, or on the left, or two separate objects with half the area each, (or a bigger but less reflective object), etc.

If you have an array of sensors, then you can resolve most of that by math alone, but for good results you need a whole lot of sensors (or positions of the same sensor) and it gets difficult and expensive.

But the idea here is that of all the mathematically possible scenes producing a given return, virtually none are plausible, so you can just guess at a plausible scene and refine your guess until it explains the result. That kind of guessing is the one category of problem where neural networks are actually the best solution. Especially if you know what you’re looking for (like a hand) and just want to know what position it’s in.

I think the thought here is that, if measured from enough different viewpoints, it should be possible to just row-reduce and solve the data for the voxels of the object ala Computed Tomography.

What they’re doing is compressed sensing followed by applying deep learning to the reconstruction problem. Scratch the “low-cost” and “tiny sensor” part and the length scale involved which are more of a means to an end with conceivable experimental validation.

Here’s the acoustic equivalent:

“Compressive 3D ultrasound imaging using a single sensor”

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.1701423

Author of the paper here. Totally correct about compressed sensing. But I’d argue there’s no deep learning being used here. The neural network is just used as a representation of the scene, there is no inductive bias (i.e., the network has not seen any data prior to use for reconstruction).

Yeah, any phone already has better 3d scanning capability than this

Actually doesn’t need to use sensor to reconstruct a object . i see another approach using software and computation on a picture to attempt to reconstruct a object (apple did ) . they use a method (as my Guess) ,first they isolate the object, then break down it , put into Matrix, and replot on their coordinate . due to 1 pixel on a picture also can be 1 pixel on 3D , that mean with several picture from many edge, they can reconstruct a 3D object. Then they can use Ai for that bunch data for better look .

As i remember this paper already exist long time ago . to make the result looking real , they add a sensor for photographic.it help algorithm isolate object better.

This also AI imagine processing for ML . however hardware approach is cheaper ,because memory usage for these algorithm as high as hell .

I see company using laser mixed with a lot of sensor for fine-turning approach .