Today, we think nothing of sticking thousands of pages of documents on a tiny SD card, or just pushing it out to some cloud service. But for decades, this wasn’t possible. Yet companies still generated huge piles of paper. What could be done? The short answer is: microfilm.

However, the long answer is quite a bit more complicated. Microfilm is, technically, a common case of the more generic microform. A microform is a photographically reduced document on film. A bunch of pages on a reel of film is microfilm. If it is on a flat card — usually the size of an index card — that’s microfiche. On top of that, there were a few other incidental formats. Aperture cards were computer punch cards with a bit of microfilm included. Microcards were like microfiche, but printed on cardboard instead of film.

In its heyday, people used specialized cameras, some made to read fanfold computer printer paper, to create microfilm. There were also computer output devices that could create microfilm directly.

How Did That Happen?

Although microfilm really caught on in the mid-20th century, it is much older than that. John Benjamin Dancer appears to have been the first to reduce documents by about 160:1 using daguerreotypes in 1839. He also used wet collodion plates later, but didn’t see any real point to the work.

However, two astronomers, James Glaisher and John Herschel, did see the value of the technology in the early 1850s. By 1870, carrier pigeons were carrying newspaper pages by microfilm into blockaded Paris during the Franco-Prussian War’s Siege of Paris, thanks to René Dagron. During the relatively short conflict, about 115,000 messages had flown by pigeon.

However, two astronomers, James Glaisher and John Herschel, did see the value of the technology in the early 1850s. By 1870, carrier pigeons were carrying newspaper pages by microfilm into blockaded Paris during the Franco-Prussian War’s Siege of Paris, thanks to René Dagron. During the relatively short conflict, about 115,000 messages had flown by pigeon.

The technology languished for a while, although Reginald A. Fessenden did suggest in 1896 that engineering documents would be a good thing to microfilm, proposing 150 million words in a square inch of film. In fact, nearly a century later, many electronic vendors made their databooks and application notes available on microfiche.

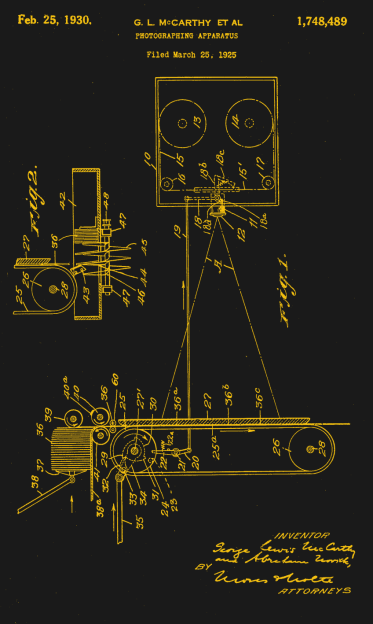

However, it would be 1920 before we see “modern” microfilm usage. The Checkograph, a device patented in 1925 by George McCarthy (with a US Patent in 1930), let banks store cancelled checks on film. Kodak acquired the device in 1928 and rebranded it Recordak.

As you might expect, big libraries jumped right in. Starting in the late 1920s, libraries including the British Library and the Library of Congress adopted microforms. Kodak started filming The New York Times for distribution, while Harvard University Library started filming foreign newspapers in 1938.

While most uses of microfilm are made to save storage space, it can also help save space for carrying mail, as the military did during World War II.

Alternatives

There were many less-than-successful attempts to bring microfilm into the hands of readers. Retired Navy Admiral Bradley Allen Fiske created the Fiske-O-Scope. The earliest designs had two eyepieces, but they eventually evolved into a single-eye viewing scope. A roller shifted the eyepiece along the reading material, which, initially, were long sheets of paper. Eventually, the Fiske-O-Scope changed to film.

You can see the Admiral using his device, along with some reading material in the accompanying figure. Although the experience of reading with the Fiske-O-Scope may have left something to be desired, the concept itself was clearly well ahead of its time. Ultimately, it promised to let the user carry their personal library around with them — an idea that arguably wouldn’t truly be realized until the birth of the modern e-reader.

Like many great ideas, there wasn’t a single point where the perfect machine appeared. It was more of a slow ooze. There was clearly a need to compress stored documents. It just needed the right equipment.

Equipment and Film

Early microforms were projected with conventional equipment like a magic lantern or eyeballed with a magnifier. However, modern readers generally project onto the rear of a glass screen. More expensive ones could even print what was on the screen using a photocopier-like mechanism.

The University of Arizona has a video showing how to use a classic reader, which you can watch below. Their fancy reader can handle both microfilm and microfiche.

The Hoover Institution Library has a moderately recent video about using their super-modern microfilm reader if you would like to have a peek at how to use one. Note this one uses a computer, so the experience isn’t as authentic as using an old 1960s reader.

Film reels tend to be either 16 mm or 35 mm, and some machines could do either. Typically, 35 mm microfilm was the order of the day for large-format scans. Letter-sized material commonly went on 16 mm film. Sometimes the film was on an open reel. Other times, it would be in a cartridge. There were M-type cartridges and ANSI cartridges (and probably others).

Either way, the film could have a single image per frame (simplex) or two images, such as the front and back of a document, per frame. That’s a duplex microfilm.

Some systems used “blips” at the edge of the film to mark when an image starts so that all the pages don’t have to be the same size. Nice machines could count the blips so if someone told you look on “roll 295, frame 952,” you could load the right roll, set the counter to 952, and let the machine fast forward, counting blips, until the counter went to zero and the machine stopped.

Super fancy machines used a double blip to mark the start of a document. This allows you to refer to “roll 295, document 3, frame 80” or — more commonly — to tell the machine to skip to the next document.

Microfiche cards varied somewhat, but were normally very close to 4×6 inches. Jacket versions held strips of film, but specially-made microfiche cards might be just a single sheet of film.

Computer Output Microfilm

The easiest way to create microforms, though, was to have the computer do it directly. Early models displayed data on a CRT, so a camera could snap a picture. By 1977, though, you could get machines that used a laser to directly write on the output medium. COM — Computer Output Microfilm (or Microform) — was widely used, although some mainframe computers sent tapes to service companies to actually make the microfilm.

IBM’s second attempt at COM was the IBM 1360, but it ultimately didn’t take off, either. It wasn’t exactly a COM output device but a way to store a whopping 128 GB on photographic film cards. There were only six made.

The biggest producer of COM output devices was probably Stromberg Carlson. Kodak was another big name. The Komstar series was made to connect to IBM computers as if they were actual printers. There was also a model made to connect to a magnetic tape drive. These were made well into the 1990s.

Microfilm Today

Most things today are in digital form and a great deal of old microform records are now in digital form, too. However, there was such a flood of microforms that there are still records that you need to find a reader to see them. The Internet Archive, as you might expect, digitizes a lot of microform documents and, if you are watching at the right time, you can look over their shoulder while they do it.

Of course, in addition to military mail, extreme microfilm works for spies, too. If you find a cache of microfiche cards, you can always build your own reader.

I remember using laser film recorders in high school to output documents at some 6000 dpi onto negatives that would then be contact printed onto plates for the printing press. Absolutely insane the level of resolution technology got to before we were able to produce “good enough” results with now normal digital copiers.

By ca. 1990, PCs running Win3.1/Macs running System 7 could work with images of up to 2048×3072 or 4096×6144 pixels.

CRT monitors capable of 1600×1200 pixel resolution were available, too.

Most PC consumer graphic cards from 1988-1990 could do 1024×768 pixel at 256c.

Trident 8900, PVGA1A/B/C, ET-4000AX, OAK OTI-67 etc.

It was just a matter of enough video RAM (512K, 1MB) and the RAMDAC.

The RAMDAC was socketed, a 256c type by default.

For more than 256c, it had to be replaced.

Drivers for Windows/386, Windows 3, AutoCAD, P-CAD, Wordperfect, GEM, Ventura Publisher, VESA VBE 1.x and so on were on the supplied driver diskettes.

Unfortunately, most users had lost the disks, so they were limited to VGA. So sad.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photo_CD

“They didn’t market it, but a single unit made it to the Social Security Administration.”

Oh great, now the “obsolete” moniker will never leave the agency. From mainframes to COBOL, and now microfilm. Next up, AI on a Babbage engine.

“Next up, AI on a Babbage engine.”

^^– coming soon to Hackaday

Ada Countess of Lovelace actually suggested having an analytical engine compose poetry or write music. Its descendants can now do that, but if she had actually tried running a large language model on the analytical engine, it would still be running today.

If you want to pull up an old newspaper you will still get it as microfiche at your l library…

I remember a repair shop I use to go to had the manuals on microfiche.

Dealership parts departments commonly had the parts diagrams on microfiche too.

I still have a reader and about a thousand microfiche. Don’t know why. But I guess I could demonstrate archaic 20th century parts lookup one day.

Except when you can’t. At least one medium-sized-city library in the United States discarded its local newspaper microfilms. My “gut” says it was a buy-off (or worse, strong-arming) from the newspaper so the paper could control and monetize access to its archives.

Other libraries have lost collections due to fire, flood, or other disasters.

And they don’t want readers to be able to see how their editorial standards have slipped.

Back in the ’80s, part of my job was to pull up loan history information from microfiche.

Those were not the good old days.

Microdots.

“Microfilm is, technically, a common case of the more generic microform. A microform is a photographically reduced document on film.”

Why this sentence is all kinds of topsy-turvy is left an exercise.

Does anyone know how much data (in bytes) a 16mm frame can hold? (maybe in qr code for example)

This brings back memories of my first after-school job in the Babcock & Wilcox computing center in central VA, circa 1980. It was a CDC mainframe shop, and they had a pair of COM machines. They wouldn’t trust or train a high school kid to change out the chemical and film stocks (never mind that I’d probably had more experience handling chemicals than any of them), but I got to sort the output. It was fascinating for a kid, especially a nearsighted one!

REALLY strong smell of vinegar around those machines. I assume part of the process used glacial acetic acid.

I used to work at a bank that used microfilming for customer correspondence. The cameras were about a meter square and 1.5 meters tall. They did fast feed: you could fit about 2,000 documents on a single roll of film.

We had two varieties of microfilm printers, all from Kodak. The older ones were electronic, not computerized, and had large hoppers for toner which we filled from bottles; you can imagine the dust… The newer printers had an IBM PC in the base of the cabinet and were connected to an external printer via token ring. The original design used a 286, i think: I remember when the service reps had to replace the hard drive on one, they brought in the smallest hard drive they could find – I think it was around 15 gb at the time – and formatted it down to ~half a gigabyte.

Still in use when I left the company in 2007; for all I know, they’re still going.

I worked on a microfiche printer back in the 90’s — it was a machine the size of a large copier that spat out laser etched blue 4×6 cards, each with over 100 tiny pages. Insurance companies used them to print backups from tape, then store them in what looked like a shoebox. Lord help you if you dropped the shoebox and spilled it!

I used to handle IBM punch cards in my high school days and we always ran a black magic marker diagonally across the top of the cards after they were packed in a box. That way, if the cards fell out, you could resort them properly by lining up the black spots at the top of each card.