As the Industrial Age took the world by storm, city centers became burgeoning hubs of commerce and activity. New offices and apartments were built higher and higher as density increased and skylines grew ever upwards. One could live and work at height, but this created a simple inconvenience—if you wanted to send any mail, you had to go all the way down to ground level.

In true American fashion, this minor inconvenience would not be allowed to stand. A simple invention would solve the problem, only to later fall out of vogue as technology and safety standards moved on. Today, we explore the rise and fall of the humble mail chute.

Going Down

Born in 1848 in Albany, New York, James Goold Cutler would come to build his life in the state. He lived and worked in the growing state, and as an architect, he soon came to identify an obvious problem. For those occupying higher floors in taller buildings, the simple act of sending a piece of mail could quickly become a tedious exercise. One would have to make their way all the way to a street level post box, which grew increasingly tiresome as buildings grew ever taller.

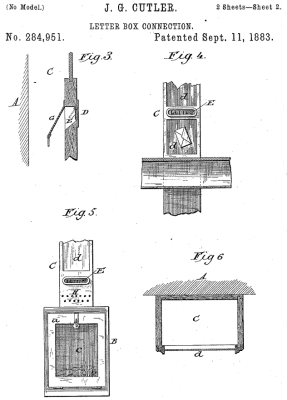

Cutler saw that there was an obvious solution—install a vertical chute running through the building’s core, add mail slots on each floor, and let gravity do the work. It then became as simple as dropping a letter in, and down it would go to a collection box at the bottom, where postal workers could retrieve it during their regular rounds. Cutler filed a patent for this simple design in 1883. He was sure to include a critical security feature—a hand guard behind each floor’s mail chute. This was intended to stop those on lower levels reaching into the chute to steal the mail passing by from above. Installations in taller buildings were also to be fitted with an “elastic cushion” in the bottom to “prevent injury to the mail” from higher drop heights.

One year later, the first installation went live in the Elwood Building, built in Rochester, New York to Cutler’s own design. The chute proved fit for purpose in the seven-story building, but there was a problem. The collection box at the bottom of Cutler’s chute was seen by the postal authorities as a mailbox. Federal mail laws were taken quite seriously, then as now, and they stated that mailboxes could only be installed in public buildings such as hotels, railway stations, or government facilities. The Elwood was a private building, and thus postal carriers refused to service the collection box.

It consists of a chute running down through each story to a mail box on the ground floor, where the postman can come and take up the entire mail of the tenants of the building. A patent was easily secured, for nobody else had before thought of nailing four boards together and calling it a great thing.

Letters could be dropped in the apertures on the fourth and fifth floors and they always fell down to the ground floor all right, but there they stated. The postman would not touch them. The trouble with the mail chute was the law which says that mail boxes shall be put only in Government and public buildings.

–The Sun, New York, 20 Dec 1886

Cutler’s brilliantly simple invention seemed dashed at the first hurdle. However, rationality soon prevailed. Postal laws were revised in 1893, and mail chutes were placed under the authority of the US Post Office Department. This had important security implications. Only post-office approved technicians would be allowed to clear mail clogs and repair and maintain the chutes, to ensure the safety and integrity of the mail.

With the legal issues solved, the mail chute soared in popularity. As skyscrapers became ever more popular at the dawn of the 20th century, so did the mail chute, with over 1,600 installed by 1905. The Cutler Manufacturing Company had been the sole manufacturer reaping the benefits of this boom up until 1904, when the US Post Office looked to permit competition in the market. However, Cutler’s patent held fast, with his company merging with some rivals and suing others to dominate the market. The company also began selling around the world, with London’s famous Savoy Hotel installing a Cutler chute in 1904. By 1961, the company held 70 percent of the mail chute market, despite Cutler’s passing and the expiry of the patent many years prior.

The value of the mail chute was obvious, but its success was not to last. Many companies began implementing dedicated mail rooms, which provided both delivery and pickup services across the floors of larger buildings. This required more manual handling, but avoided issues with clogs and lost mail and better suited bigger operations. As postal volumes increased, the chutes became seen as a liability more than a convenience when it came to important correspondence. Larger oversized envelopes proved a particular problem, with most chutes only designed to handle smaller envelopes. A particularly famous event in 1986 saw 40,000 pieces of mail stuck in a monster jam at the McGraw-Hill building, which took 23 mailbags to clear. It wasn’t unusual for a piece of mail to get lost in a chute, only to turn up many decades later, undelivered.

The final death knell for the mail chute, though, was a safety matter. Come 1997, the National Fire Protection Association outright banned the installation of new mail chutes in new and existing buildings. The reasoning was simple. A mail chute was a single continuous cavity between many floors of a building, which could easily spread smoke and even flames, just like a chimney.

Despite falling out of favor, however, some functional mail chutes do persist to this day. Real examples can still be spotted in places like the Empire State Building and New York’s Grand Central station. Whether in use or deactivated, many still remain in older buildings as a visible piece of mail history.

Better building design standards and the unstoppable rise of email mean that the mail chute is ultimately a piece of history rather than a convenience of our modern age. Still, it’s neat to think that once upon a time, you could climb to the very highest floors of an office building and drop your important letters all the way to the bottom without having to use the elevator or stairs.

Collage of mail chutes from Wikimedia Commons, Mark Turnauckas, and Britta Gustafson.

Good read. Thank you.

There’s one in my building where I work. Mighty handy, but I get the plenum issue. Too bad really.

My office has one too, still being used. The building is from the 1930s.

These days I’d imagine a bit of fairly simple fire-stopping or a few baffles would solve that well enough.

this was quite the HACK for back in the DAY.

yep back in the day where the first technology to start the process was a fancy reservoir fountain pen in hand, dropped into a fancy futuristic letter sending tunnel, transported by hand and foot or horse or horsepower, then received to be opened by an ornate Japanese letter opener engineered in miniature of the famous samurai sword makers. “to my dearest betty…”

or maybe it started with a ballpoint pen, tossed into a hole on the 3rd floor, crumpled into a mail bag, and eventually opened with a fingernail. “to whom it may concern…”

Back in the ’90s, my employers 35-story downtown Chicago building repurposed their mIl chutes as a fiber raceway for intranet traffic. They left the ornate art-deco covers but sealed the mail slots and painted the backside of the glass black.

Guess the idea of clear chutes never occurred. Anyway next story should be pneumatic tubes since mail and them kind of go together.

All the mail chutes I have seen have a glass (originally – probably something newer now) front panel. This is to help locate blockages.

A (circa 1932) building I used to work in had wire reinforced glass, running the full length of the visible front of the chutes.

Clear chutes? Mail chutes had glass windows on each floor and you could watch the letters fall past. I remmeber seeing them in action circa 1963 in office buildings in downtown Dallas – I was alittle kid and seeing the letters fall by seemed exciting.

So is an elevator shaft. Or a stairwell. Stairwells can be closed off with firedoors at intervals, but not elevator shafts.

The codes with which I’m familiar require elevator doors to take fire safety into account. The most lax code required every elevator door except the ground floor to have a smoke seal. The most strict code required every door to be at least 1 hour rated and have a smoke seal, and to sometimes have an additional slam door with its own rating.

I would love to have some of those doors! I have no idea what I would do with them, though.

Cool read. I had one, but for trash ;)

Gasp… It was YOU!

That chute was SUPPOSED to be for LAUNDRY!

The length Americans will go to avoid physical exercise….

It’s amazing how many people will take a 30 minute walk to a mailbox to avoid doing work…