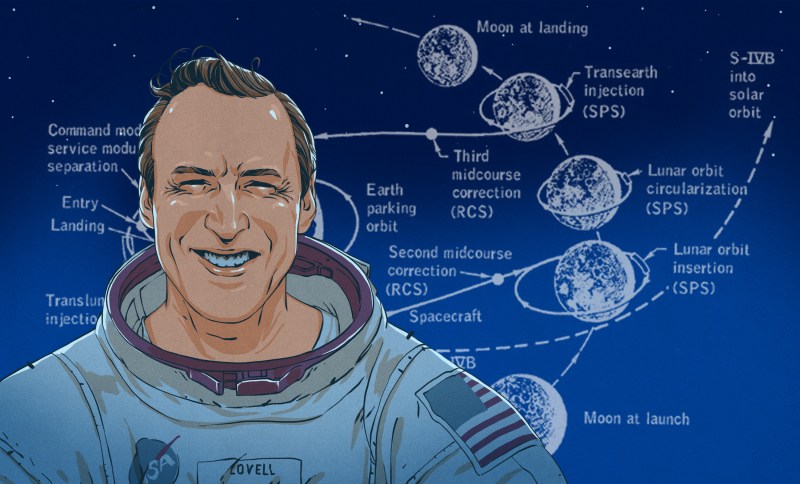

Many people have looked Death in the eye sockets and survived to tell others about it, but few situations speak as much to the imagination as situations where there’s absolutely zero prospect of rescuers swooping in. Top among these is the harrowing tale of the Apollo 13 moon mission and its crew – commanded by James “Jim” Lovell – as they found themselves stranded in space far away from Earth in a crippled spacecraft, facing near-certain doom.

Lovell and his crew came away from that experience in one piece, with millions tuning into the live broadcast on April 17 of 1970 as the capsule managed to land safely back on Earth, defying all odds. Like so many NASA astronauts, Lovell was a test pilot. He graduated from the US Naval Academy in Maryland, serving in the US Navy as a mechanical engineer, flight instructor and more, before being selected as NASA astronaut.

On August 7, 2025, Lovell died at the age of 97 at his home in Illinois, after a dizzying career that saw a Moon walk swapped for an in-space rescue mission like never seen before.

Joining The Navy

James Arthur Lovell Jr. was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on March 25, 1928. He was the sole child, with his father dying in a car accident when he was five years old. After this he and his mother lived with a relative in Indiana, before moving to Wisconsin where Lovell attended Juneau High School. He attained the Boy Scouts’ highest rank of Eagle Scout, while also displaying an avid interest in rocketry including the building of flying models.

After graduating from high school, Lovell studied engineering under the US Navy’s Flying Midshipman program from 1946 to 1948, which focused on training new naval aviators. This was a sponsored program by the US Navy, with the student required to enlist as Apprentice Seaman and to serve in the Navy for five years, including one year of active duty.

As this program was being rolled back in the wake of the end of WW2, Lovell saw himself and others like him pressured to transfer out, with Lovell applying at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. Here he would continue his engineering studies, graduating with a Bachelor of Science degree in the Spring of 1952.

After graduation he was commissioned as an ensign in the US Navy, got selected for naval aviation training and was later assigned to the Essex-class aircraft carrier USS Shangri-La during the 1950s where he flew many missions, racking up a reported total of 107 carrier landings. Once back ashore he became a flight instructor for Navy pilots.

To Space And Beyond

With NASA selecting its future astronauts from the military’s test pilots for a variety of reasons, it was only a matter of time before Lovell would be in the running for the first group of astronauts considering his performance in the Navy. Although he got put on the list of potential astronauts for Project Mercury, he narrowly missed joining the Mercury Seven. After applying for the second group, however, he ended up being selected for Mercury’s successor project: Project Gemini.

Lovell would fly on two Gemini missions, Gemini 7 and Gemini 12, with the latter seeing Lovell being joined by Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin as the pilot. Before embarking on Gemini 7, Lovell and his fellow astronaut Frank F. Borman were given the advice by Pete Conrad – who had previously spent eight days on Gemini 5 – to take books along for the ride. Considering that Gemini 7 was an endurance mission lasting nearly two weeks, this turned out to be very good advice, indeed.

The four-day Gemini 12 mission would be the last mission in the project, taking place during November of 1966. During this mission Aldrin demonstrated a number of extra-vehicular activities (EVAs), showing that humans could perform activities outside of the spacecraft, thus clearing the way for Project Apollo.

Lucky Apollo 13

Although Lovell is generally associated with Apollo 13, his third spaceflight was on Apollo 8 which launched on December 21st of 1968. This was the first manned Apollo mission to make it to the Moon following Apollo 7 which stayed in Earth’s orbit. During Apollo 8 the crew of three – Borman, Lovell and Anders – completed ten orbits around Earth’s companion, making it the first time that humans had laid eyes on the far side of the Moon and were able to observe an Earthrise.

With the Apollo program in constant flux, Apollo 8’s mission profile was changed from a more conservative Earth orbit-bound test with the – much delayed lunar module (LM) – to the very ambitious orbiting of the Moon. This put the Apollo program back on track, however, as it skipped a few intermediate steps. After Apollo 9 demonstrated the full lunar EVA suit in space as well as docking with the LM in Earth orbit, Apollo 10 was the wet dress rehearsal for the first true Moon landing with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin taking the honors.

After Apollo 12 delivered its second batch of astronauts to the lunar surface, it was finally time for Lovell as the commander and Fred Haise as the LM pilot to add their footprints to the lunar regolith as part of the Apollo 13 mission. After two successful Moon landings, when Apollo 13 took off from the landing pad on April 11, 1970, it seemed that this was going to be mostly a routine mission.

After making it about 330,000 km from Earth, the Apollo 13 crew was going through their well-practiced schedule, with only one active issue bothering them and ground control in Houston. This issue involved the pressure sensor in one of the service module (SM) oxygen tanks. Ground control requested that the crew try activating the stirring fans in the oxygen tanks to see whether de-stratifying the contents of the affected oxygen tank might fix the odd readings.

Ninety-five seconds after Command Module (CM) pilot John Swigert activated these fans the three astronauts heard a loud bang, accompanied by electrical power fluctuations and the attitude control thrusters automatically engaging. After briefly losing communications with Earth, Swigert called back to Houston with the now famous “Houston, we have had a problem.” phrase.

As indicated by the resulting investigations, one of the oxygen tanks (Oxygen Tank 2) that fed the fuel cells for power generation had turned into a bomb owing to manufacturing and handling defects years prior. The resulting explosion also caused the loss of Oxygen Tank 1 and ultimately put all of the CM’s fuel cells out of commission. With the CM’s batteries rapidly draining, the Apollo 13 astronauts only had minutes to put a plan together with Houston to use the LM as their lifeboat and to devise a way to plan a course back to Earth after a fly-by of the Moon.

As these immediate concerns were addressed and Apollo 13 found itself on a course that should take it safely back to Earth, two new issues cropped up. The first was that of potable water, as normally the CM’s fuel cells would create all the water that they’d need during the mission. With the CM and its fuel cells out of commission, they had to strictly ration their limited supply, all the way down to 200 mL per person per day.

The other issue concerned the carbon dioxide levels. Although the LM carried sufficient oxygen, CO2 scrubbers were required to keep the levels of this gas at healthy levels, even as the crew kept adding to it with their breathing. The lithium hydroxide pellet-based scrubbers in the CM and LM were up to their individual tasks, but the LM was equipped only for the 45 hours that two astronauts would spend on the lunar surface, not keep three astronauts alive for the time that it’d take to travel back to Earth.

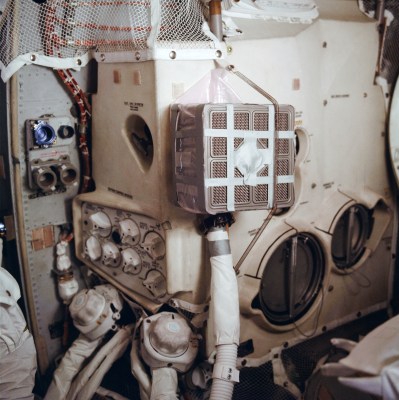

Annoyingly, the CM and LM scrubber canisters had different dimensions that prevented the astronauts from simply availing themselves of the CM scrubbers. This was fortunately nothing that some solid arts and crafts experience can’t fix, and the CM canisters were made to work using plastic manual covers, duct tape, and whatever else was needed to bridge the gaps.

With all the essentials dealt with as well as possible considering the circumstances, the three astronauts set in for a very long and very cold wait. As most systems were shut down to preserve every bit of energy, there was little any of them could do against the cold of space itself seeping into the LM, even as moisture condensed on all surfaces.

Before nearing Earth, Lovell and his crew were tasked with configuring the LM’s navigation computer in preparation for final approach, as well as starting the CM up from its cold shutdown. With every step of this re-entry and required separation of the SM, CM, and ultimately the LM being completely unlike the normal procedure that they had trained for, there existed significant uncertainty about how well it all would work.

Fortunately, everything went off relatively without any issues, and on April 17, 1970, all three Apollo 13 astronauts made a soft splashdown on Earth. This would also be Lovell’s fourth and final spaceflight.

Retirement

Lovell would retire from the Navy and the space program on March 1, 1973. For decades afterwards, he’d serve as CEO, president, and similar roles for a range of companies before retiring in 1991, only staying on the board of directors for a number of corporations, including the Astronautics Corporation of America. With the fame that Apollo 13 had brought him and his two fellow astronauts, none of them ever fully left the public eye.

A number of films and documentaries were made about the Apollo 13 mission, which was termed a ‘successful failure’. Lovell would make a number of cameos, with the 1995 film Apollo 13, based on Lovell’s book Lost Moon, being one of the most notable examples.

With Lovell’s death, Fred Haise is now the last remaining member of Apollo 13 to still be alive, after Jack Swigert died from cancer in 1982.

Although a lot has been said already about Apollo 13 nearly ending in tragedy, including its inauspicious number in many Western cultures, it’s impossible to deny that this mission’s crew were among the luckiest imaginable. In the dark and cold of Space, trapped between Earth and the Moon, they found themselves among the best friends imaginable to together solve a puzzle, even as their own lives were on the line.

If the oxygen tank had exploded on the return trip from the Moon, all astronauts would have likely perished. Similarly, if any of the other events during the mission had played out slightly differently, or if another emergency had occurred on top of the existing ones, things might have turned out very differently.

If there’s anything to be learned from Lovell’s life, it is probably that ‘luck’ is relative, and that team work goes a very long way.

Surely the ultimate hack!

Especially when it is a matter of life or death… And no store to pick up things you need… Or a shop with tools, or …

…Or literally anything for hundreds of thousands of kilometers in any direction. Just what you got in your tin can, make it work or everyone including you croaks. Talk about pressure!

I only wish to add: listen to the BBC World Service’s podcast “13 minutes to the moon”, the first season covers the manned space flight program up to Apollo 10, the second season is Apollo 13.

Listen to it, there are brilliant interviews with some of the people involved, including James Lovell. Remember the men and women involved in that program and their contributions in space as well as on the ground.

Agreed. It’s a very good podcast. The 3rd season is about half released right now and covers the Space Shuttle.

This is a prime example of why I never unsubscribe from a good podcast. You never know when it might come back.

This man really had a fuguri-hard attitude to life. Shame he’s gone.

” including its auspicious number in many Western cultures” needs an edit.

Having personally met Jim Lovel in 1995, and having a while to converse with him, I found that he was soft spoken with consumate humility. Irespective of his larger than life reeputatiion,

But someone tell me how he can 97 when he died cause it’s clearly stated that at the age of 5 he joined navy in 1928. So he was 5yrs old in 1928 he was born in 1923 logically so he would be 102 yrs old possibly but idk, I’m confused.

You guys tell me if I’m wrong somewhere.

James Arthur Lovell Jr. was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on March 25, 1928. Which means he was 97 when he died August 7, 2025. When Lovell was 5, in 1933, his father died. He was 17 at the end of WWII.

It is important to remember that while they were lucky they also had thousands of hours of training and simulations. Without the training their luck would have quickly run out.

They also credited the grounding of the original CM pilot as a factor in their survival. Apparently he had the best knowledge of how all the systems interacted. Unlikely that others could have figured out the restart sequence in time.

Saw the movie about that in cinema as a kid and loved it.

“If the oxygen tank had exploded on the return trip from the Moon, all astronauts would have likely perished.”

Can anyone explain this?

The lunar module would have been jettisoned before leaving lunar orbit. They wouldn’t have had any access to the then depleted power of the LM, nor the LM’s scrubbers.