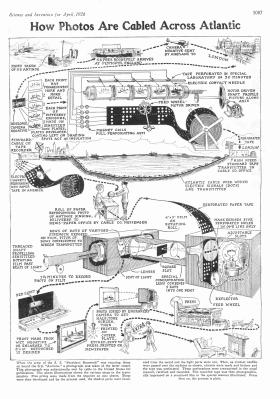

Of course, the answer is analog fax. But think about it. How would you create an analog fax machine in 1926? The graphic is quite telling. (Click on it to enlarge, you won’t be disappointed.)

If you are like us, when you first saw it you thought: “Oh, sure, paper tape.” But a little more reflection makes you realize that solves nothing. How do you actually scan the photo onto the paper tape, and how can you reconstitute it on the other side? The paper tape is clearly digital, right? How do you do an analog-to-digital converter in 1926?

It Really is a Wire PHOTO

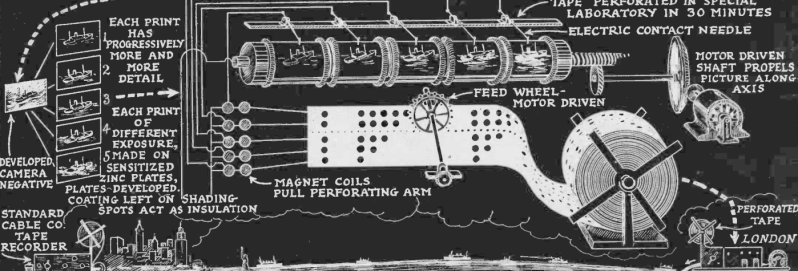

The graphic is amazingly technical in its description. Getting the negative from Plymouth to London is a short plane hop. From there, a photographer creates five prints on specially-coated zinc plates. Where the emulsion stays, the plate won’t conduct electricity. Where the developer removes it, electricity will flow.

Why five? Well, each print is successively darker. All five get mounted to a drum with five brushes making contact with the plate. Guess how many holes are in the paper tape? If you guessed five, gold star for you.

As you can see in the graphic, each brush drives a punch solenoid. It literally converts the brightness of the image into a digital code because the photographer made five prints, each one darker than the last. So something totally covered on all five plates gets no holes. Something totally uncovered gets five holes. Everything else gets something in between. This isn’t a five-bit converter. You can only get 00000, 00001, 00011, 00111, 011111, and 11111 out of the machine, for six levels of brightness.

Decoding

The decoding is also clever. A light passes through the five holes, and optics collimates the light into a single beam. That’s it. If there are no holes in the tape, the beam is dark. The more holes, the brighter it gets. The light hits a film, and then it is back to a darkroom on the other side of the ocean.

The rest of the process is nothing more than the usual way a picture gets printed in a newspaper.

If you want to see the graphic in context, you can grab a copy of the whole magazine (another Hugo Gernsback rag) at the excellent World Radio History site. You’ll also see that you could buy a rebuilt typewriter for $3 and that the magazine was interested if the spirits of the dead can find each other in the afterlife. Note this was the April issue. Be sure to check out the soldering iron described on page 1114. You’ll also see on that page that Big Mouth Bill Bass isn’t the recent fad you thought it was.

We are always fascinated by what smart people would develop if they had no better options. It is easy to think that the old days were full of stone knives and bear skins, but human ingenuity is seemingly boundless. If you want to see really old fax technology, it goes back much further than you would think.

OK, I get it. The bandwidth required to send the photo would be more than the cable could handle, so they “downsample” it onto the paper tape, which can then be sent slowly. Clever.

I think this misses the point. There is probably no in intentional “down sampling” here. A copper cable in 1920 had comparable “bandwidth” to one in 2025. The technological feat here is the scanning technology that turned a photo into 0s and 1s that could be sent with copper wires at all.

In late 1920’s the max speed of transmission over transatlantic cable was around 400 words per minute. Go too fast and signal gets too distorted to be decoded.

Very big rabbit hole here with the Hugo link. This was in the player piano era.

“Photo copied by engravers’ camera to get half-tone screen.” Y’know, I always wondered how they did that. Looks like Wikipedia has the answer. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halftone

Fascinating!

Not just a fishy trophy loudspeaker in that 1926 zine but a candlestick made of a chicken foot. Love that DIY stuff magazines had then. What a rabbit hole!

Still quite a bit of functional schematics in those old mags too, provided you can find modern equivalents for obsolete bits.

Ok, perhaps a mundane question but on the paper tape there are 5 parallel holes. When the message was sent across the wire were these – let’s call them bits – sent serially or were the groups of 5 “bits” somehow encoded? I assume there was one wire so there must have been some strategy to take the data off the paper tape send it over the one wire then decode it?

It probably uses the Baudot start stop system, is invented in the 1870’s. Bits are serially sent.

Sounds very plausible thank you for the reply

Looks like a standard 5 bit BAUDOT teletype, so the bits are sent serially like “modern” serial ports.

Thanks Bill sounds very reasonable

Absolutely fascinating article! And the story of the rescue of the S.S. Antinoe is a wonderful read itself: https://www.marinersmuseum.org/2018/04/death-rides-the-storm-the-story-of-one-amazing-rescue/

Three years later, the same captain who rescued the S.S. Antinoe rescued another ship, the S.S. Florida: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Fried. Quite a career!