As a Hackaday writer, I see a lot of web pages, social media posts, videos, and other tips as part of my feed. The best ones I try to bring you here, assuming of course that one of my ever-vigilant colleagues hasn’t beaten me to it. Along the way I see the tropes of changing content creator fashion; those ridiculous pea-sized hand held microphones, or how all of a sudden everything has to be found in the woods. Some of them make me laugh, but there’s one I see a lot which has made me increasingly annoyed over the years. I’m talking of course about the craftsman myth.

No. The Last True Nuts And Bolts Are Not Being Made In Japan

If you don’t recognise the craftsman myth immediately, I’m sure you’ll be familiar with it even if you don’t realise it yet. It goes something like this: somewhere in Japan (or somewhere else perceived as old-timey in online audience terms like Appalachia, but it’s usually Japan), there’s a bloke in a tin shed who makes nuts and bolts.

But he’s not just any bloke in a tin shed who makes nuts and bolts, he’s a special master craftsman who makes nuts and bolts like no other. He’s about 120 years old and the last of a long line of nut and bolt makers entrusted with the secrets of nut and bolt making, father to son, since the 8th century. His tools are also mystical, passed down through the generations since they were forged by other mystical craftsmen centuries ago, and his forge is like no other, its hand-cranked bellows bring to life a fire using only the finest cedar driftwood charcoal. The charcoal is also made by a 120 year old master charcoal maker Japanese bloke whose line stretches back to the n’th century, yadda yadda. And when Takahashi-san finally shuffles off this mortal coil, that’s it for nuts and bolts, because the other nuts and bolts simply can’t compare to these special ones.

Purple prose aside, this type of media annoys me, because while Takahashi-san and his brother craftsmen in Appalachia and anywhere else in the world possess amazing skills and should without question be celebrated, the videos are not about that. Instead they’re using them as a cipher for pushing the line that The World Ain’t What It Used To Be, and along the way they spread the myth that either there are no blokes in tin sheds left wherever you live, or if there are, their skills are of no significance. Perhaps the saddest part of the whole thing is that there are truly disappearing crafts which should be highlighted, but they probably don’t generate half the YouTube clicks so we don’t see much of them.

Celebrate your Local Craftsmen

My dad was a craftsman in a tin shed, just like the ones in the videos but in central southern England. Partly as a result of this I have known and dealt with a lot of blokes in tin sheds throughout my lifetime, and I am certain I would feel right at home standing in that Japanese one.

Part of coming to terms with the disturbed legacy of my own dysfunctional family has come in evaluating what from them I recognise as part of me and what I don’t, and it’s in my dad’s workshop that I realise what made me. Like all of us, he instinctively made things, usually with great success but let’s face it, like all of us too, sometimes where just buying the damn thing would have made more sense. He had truly elite skills in his craft that I will never equal, just as in my line I have mastered construction techniques which weren’t even conceived when he took his apprenticeship.

But here’s the point, my dad was not unique, and all the other blokes in tin sheds were not necessarily the same age as he was. Indeed one of the loose community of blacksmiths around where I grew up was someone who was in another year at the same school as me when I was a teenager. Even the crafts weren’t all of the mystical tools variety, I am immediately thinking of the tin shed full of CNC machine tools, or the bloke running an injection moulding operation. Believe me, both of those last two are invaluable craftsmen to know when you need their services, but they don’t fit the myth, do they? They’re not exotic.

So by all means watch those YouTube videos showing faraway folks in tin sheds and their craft, you’ll see some amazing work. But please don’t buy the mystique, or the premise that they automatically represent a disappearing world. Your part of the world will have blokes in tin sheds doing things just as impressive and useful, whether they be hand-forging steel on the anvil or working it using cutting-edge technology, and we should be seeking them out rather than lamenting a probably made-up tale from the other side of the world.

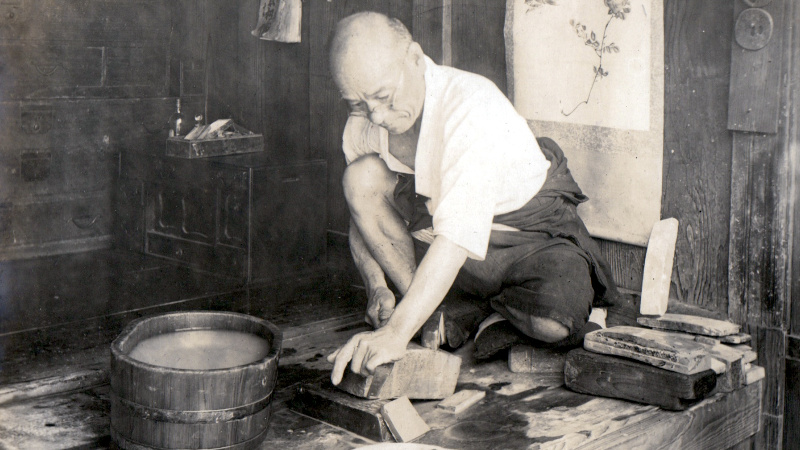

Early 20th century Japanese craftsman: Elstner Hilton, CC BY 2.0 .

There has never been a better time to tinker for the sake of the craft. The economy of it keeps changing but the access to new and old tools and materials and techniques is amazing.

Anyways this just reminds me, the off-topic rambler … when i was about 12, my dad bought a big sheet of bluecore foam and cut it up and started gluing it together. And he refused to tell us what it was supposed to be. I had the impression he was embarrassed about how much of a failure it was. It looked kind of like a canoe but it had some asymmetries that made that seem unlikely, and also of course it never could have worked structurally as a canoe so we always wondered, what was he thinking? Now i’m grown and i decided to try cornering him on it now that we’re a little closer to peers…and he just straight up said “i don’t remember doing anything like that.” But one way or the other, the failed project sat in its corner of the basement through all my teenage years. Just can’t believe he’s gonna play it like this.

Maybe he was annoyed by the symmetry of all boats and was trying to break through that convention :)

Trivia time: Venetian Gondolas are not symmetric by design. They are curved from bow to stern.

Long ago, blue foam canoes shaped.oddly were VARIEZE fuselages

I wonder when we will have the last “3D printer master” who so expertly sets up the machine as to print a piece of plastic in one go without wasting any filament, and they build all their models using the free unlicensed version of SketchUp 7.0 without so much as boolean operations to join solids, triangle by triangle, face by face.

“…triangle by triangle…

That would be an STL mystical craftsman.

A 3D printer master would be some guy keeping his Ender 3 running 30 years from now in the future, all stock.

I keep three 21 year old 3d systems printers running on cannibalized parts, transplanted materials, and sheer willpower.

Dang, disqualified myself by uprgading my tevo tarantula.

To be fair, I don’t have as much expectation that it will be a good idea to use the current crop of internet connected 3D printers for as long as my Ender 3 Pro has been in operation. It’s broadly stock, other than a new extruder arm and, recently a full metal hot end (simply to get around the Bowden being a consumable heat break).

It now resides in a corner of a warehouse, merrily turning out fun little items for curious coworkers.

Why use SketchUp? He should be writing G-code directly.

I used to work with a guy who would write documents for printing directly in Postscript, and then ftp them to the printer. Including graphical elements like flow charts.

He was a bit… odd.

tbf PS is not much different from LaTex. It’s like laughing at Donald Knuth because he can do math but he’s too old and frail to install solar panels on the roof of his house.

That Japanese craftsman makes his nuts and bolts out of steel folded 1000 times. /s

Layers != folds.

1000 folds equals 2 to the power of 1000. 2^10 = 1024 ~ 10^3, so 2^1000~10^300 which is 1 followed by 300 zeroes. I cannot compute right now, but each layer (if they are possible abd separable from neighbour layers) has the thickness smaller than if a single atom, maybe thinner than an electron.

The ancient craftsmen mastered even that without creating a black hole, and went far beyond!

https://www.xkcd.com/3033/

Hey, that´s why he is called a master craftsman. The apprentices couldn´t forge anything thinner than a micrometer …

Kids these days, smh my head

That’s (part of) the joke.

Let’s be real here: the reason japanese swordsmiths had to do all that folding stuff because they had really shitty metallurgy technology. European swords were far better, but otaku run around pretending like katanas can cut through trees…

Let’s also be real that the reason there were all the requirements around swordsmanship – endless hours of repeating the same motions, and so on – wasn’t because it was especially hard, but to make sure only either the rich, or people sponsored by the rich, could afford it. And all that pomp and circumstance and rules around battle? Just to keep peasants (who were in much better physical condition than the very physically inactive ruling elite) from running around slicing up samurai after a few weeks of training or less. Nah, see, you gotta have RULES around how you can fight with a sword!

Ditto for the swords. They have so many labor put into them to make them absurdly expensive, such that no lower-class person could possibly afford to purchase one, and if they were found with one, it could be confiscated on the excuse/assumption it was stolen. Katanas taking hundreds or thousands of man-hours was an economic way of restricting access to weapons by the ruling class.

It’s even been proven via high speed cameras that the supposedly difficult rolled-up-mat-cutting challenge can be done by a novice if they’re simply coached to move the katana correctly, in a sawing motion as the blade contacts the rolled mats. It’s not about strength or years of training to give you mystical samurai abilities and mental focus and blah blah blah.

Katanas taking several hundred man hours to make was a result of low quality ore requiring extensive forging, done without the benefit of powered tools.

Sure you can teach someone to properly move a sword to slice a tatami mat in a short period of time. And anyone can wildly swing a sharp piece of steel at a bunch of unarmed or poorly armed people and do a fair bit of damage.

Just because you can teach a few basic punches to a person in an afternoon doesnt mean theyre ready to spar with a professional boxer.

Years of training is about creating muscle memory to move correctly and instinctively under a wide array of situations and conditions so when you come across someone else with a sharp piece of steel you dont end up sliced and diced.

They were mostly training a ritual. If you do this move, then your opponent does that move, and you follow with… etc. The first one to miss a step would lose. It’s like playing knick-knack paddywhack. In some senses it’s about making a big show fight, to give each party the opportunity to yield after a suitable time without losing face.

This was exploited by at least one famous guy, who won his battles by breaking all the rules. He would arrive massively late to the battle when everyone else was already leaving, or appear in women’s clothing, fight with a spoon and a pot for weapons etc. just to confuse and piss off his opponents to the point that they would lose their composure and forget what they were doing. Then he would just stab them to death.

Nobody told him that the whole thing was just about posing between nobility and the rich, so he took it seriously and actually killed quite a few people.

Miyamoto Mushashi, if anyone wants to look into this more.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miyamoto_Musashi

Yeah for sure.

It was all just rich guys dancing for face.

Someone should have told the 30000+ samurai who died in the Battle of Sekigahara that they just needed to bow and curtsy and concede defeat.

I heard on reddit that european honor dueling was the same. Just two rich twats dancing in a field till one cried and went home to mommy. And in the old west they intentionally shot over each others heads so they would look cool to all the saloon girls. No one ever got hurt /s

It was. Especially for pistol dueling, the chances of actually hitting your opponent was minimal. Some people died, but mostly it was about showing up and not being a wuss, so both sides can save face.

Example: “… Fournier, taking out his subsequent rage on the messenger, challenged Dupont to a duel. This sparked a succession of encounters, waged with sword and pistol, that spanned decades.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Fournier-Sarlov%C3%A8ze

Dupont and Fournier dueled over 30 times over the years, and finally just agreed to let the matter go. The question is how did two officers of Napoleon not manage to kill each other? Either both of them were absolutely terrible with sword and pistol, or neither of them actually tried to.

It is estimated that for European sword dueling over 20% of combatants were killed with barely half escaping uninjured. Pistol dueling was far safer with only ~7% of duels resulting in death.

Youre assertion that these sorts of engagements were purely ego shows is ludicrous.

yep you found AN example of two dudes beefing that didnt follow through….

Alexander Pushkin: The famous poet was mortally wounded in a duel with French officer Georges d'Anthès in 1837 and died two days later. D'Anthès was accused of cheating in the duel and later married Pushkin's sister-in-law.Sir John Townshend:

He was killed by Sir Matthew Browne in a duel on Hounslow Heath in 1603. Townshend died the following day from the wounds he sustained.

Ben Jonson:

The Elizabethan playwright killed actor Gabriel Spencer in a duel in 1598. Spencer was killed, and Jonson was sentenced to hang but escaped execution by pleading “benefit of clergy”.

Francis Talbot, 11th Earl of Shrewsbury:

He was killed by the Duke of Buckingham in a duel in 1668.

Sir Henry Hobart:

The English politician was killed by Oliver Le Neve in a duel on Cawston Heath, Norfolk in 1698.

Armand d'Athos:

He was killed in a duel in 1643 and is said to have been the inspiration for a character in Alexandre Dumas's novel The Three Musketeers.

Gaston Deferre and René Ribiere:

While not a death, this duel in 1967 between two French politicians was one of the last duels to take place in France. Deferre was declared the winner after hitting Ribiere twice on the forearm with a rapier.

Felice Cavallotti: An Italian politician, he was killed in a duel with Count Ferruccio Macola in 1898 after insulting him.

And thats just a few of the more famous results. But go ahead and cherry pick another example to support your idiocy.

It’s good then that I didn’t actually say so.

Point being, even with swords 80% of the fights ended when the opponent got injured or yielded. That’s your statistics. That’s not even counting how many duels never took place.

Dueling wasn’t about killing people, it was about politics. If somebody insulted your person, just letting it go was equal to admitting to it. You had to challenge the person to maintain honor, and if they didn’t show up you’d be vindicated by default – which is what usually happened. Someone slanders you, you call them out for it, and they shut up.

If they did show up, most of the time there would be a ritualistic fight that ends with the opponent admitting “I’m wrong, sorry”, or the person demanding “satisfaction” getting a cut through and saying “You’re injured, I’m satisfied.” and the fight ends there. That’s because neither party usually wanted to risk death over a simple disagreement or insult, but since the matter became public they at least had to show up.

Some people didn’t get the point though and fought all the way to death. Like the Musashi guy, whose point in dueling was simply to kill the opponent, and why he ignored all the conventions and rules around dueling that were in place so people could let it slide and live another day.

1 in 5 resulting in death is a pretty far cry from “just about posing between nobility and the rich,”

Discounting accidents and assassinations, nobody died from dueling unless they had a death wish or they were stupid. Between gentlemen, you could always admit defeat and walk away. That was the system – that’s why there was a whole code and ritual to it.

The fact that some did or didn’t follow the rules doesn’t change the point.

Duelling changed a lot over the years. Earlier duels were much more bloody, and even a minor injury had a serious risk of going septic and killing you. It wasn’t uncommon for the winner to die within a week or so, and death rates over 100% were recorded (bystanders or seconds killed). They could be impromptu rather than formal. And certainly weren’t limited to nobles.

Later duels were more formalised, often to first blood, or would be resolved before the duel occurred.

Duels between nobles in armour were far less lethal.

But duels occurred for many reasons – formal “honour” reasons, less formal being offended/wronged and wanting revenge, and judicial duels – being the big ones I believe. All were handled differently I believe.

The church eventually outlawed duelling, though enforcement varied, and illegal duels persisted.

Wasn’t it by folding hundred times and forging, that the damascus steel was made?

(as a side note, years back, while volunteering at a local museum, I had a chance to hold one of the museum pieces, no, not damascus steel, but one of very, very interesting blades that flexed, yes, like a spring. I asked if it was fake or some kind of stage prop, no, I’ve been told, it is an old blade with a history to tell, and been passed around through generations; the handle was redone many times for different kinds of hands, and you can tell that it changed owners and been places. The origins were unclear, most likely, turkish-made, but it was definitely one of these kinds, folded many times, forged, etc, and it had distinct patina unlike damascus, just much, much fainter).

Damascus steel was crucible steel, not wrought iron. It was more to do with the particular impurities that they had where the steel came from, although the folding had an effect on evening out the mixture and making it less brittle.

Without the folding, it would still have been hard and springy, but with the added chance of a brittle inclusion or a void that would break the blade.

“Damascus Steel” was imported to Damascus from India, So it was never really an appropriate name to begin with.

Damascus steel is really Wootz steel, a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher-carbon steel, or by ferrite and pearlite banding in lower-carbon steels.

Wootz steel production largely ceased by the mid-19th century, though some traditional blades were still made into the late 19th century. The decline was due to a loss of the original process, economic factors from British rule and competition, and changes in ore composition that made it difficult to forge.

Some gunsmiths during the 18th and 19th century used the term “damascus steel” to describe their pattern-welded gun barrels, but they did not use crucible steel. Pattern-welded steel has been referred to as “Damascus steel” since 1973 when bladesmith William F. Moran unveiled his “Damascus knives” at the Knifemakers’ Guild Show. So its pretty common for people to assume Damascus to be a wrought steel product as almost all contemorary examples are.

To understand what it means, when you take a steel with impurities like carbon, carbides, nickel, tungsten, etc. (as present in the original Wootz steel), and you heat it up to a high temperature just below melting, all the different materials diffuse around and mix. if you then cool it down rapidly, you get a very fine and even grain structure, which is also very hard and brittle.

When you temper the steel, you heat it up again to a moderate temperature. The different elements can still diffuse around but slowly and less vigorously, and they start to clump up and form larger crystals with the impurities moving to the edges between the grains of pure iron, forming the characteristic bands and sheets. Then after an appropriate time, you stop the process by cooling, which locks the pattern in place.

You polish the blade and dip it in acid, and that etching would then reveal the pattern because the impurities would dissolve at a different rate than the grains and bands of pure iron, leaving their imprint on the surface.

This is the main difference between real Damascus steel and folded and pattern welded wrought steel. Back when they understood basically nothing about metallurgy, they simply got lucky to have the right sort of ore to produce the kind of steel.

Have they actually worked out what original Damascus steel was? I thought this was all just conjecture since the origins are unclear.

@dan

The article “Experiments to Reproduce the Pattern of Damascus Blades” by J.D. Verhoeven and A.H. Pendray is a scientific paper that details their experimental attempts to recreate the characteristic patterns of ancient wootz Damascus steel. They successfully reproduced several “pattern types” quite similar if not identical to historical samples. In the years that have passed since their paper several more “pattern types” have been reproduced.

Excellent info, thank you all for sharing!

“Made in India” would be interesting historical rabbit hole to follow for sure.

I think craftsmanship is the ability to take skills honed over years of practice and apply them seamlessly to a totally new challenge. Just because work is painstaking doesn’t make it craftsmanlike.

Anecdote…my mom learned how to make rosaries from her mom. They used wire to hold the beads, one piece of wire for each bead, with a hook bent into the ends like a dogbone chain. It was the first and last time she ever used needle-nose pliers and learning the technique was frustrating for her. But one day she decided to show my dad how to do it and she resented how easy it was for him, because of course he’d already put in the hours with the pliers even though he’d never seen a rosary before.

” those ridiculous pea-sized hand held microphones”

….what?

Are you referring to the Rhode bluetooth mini-mics that became all the rage starting a few years ago? Or people misusing lav mics and holding them in their fingers instead of clipping them to their shirt? Or the 70’s gameshow host handheld mic with the skinny neck?

As an audio guy I have no idea what you’re talking about.

I read it as people holding lav mics in their fingers, which I see a LOT.

Must….keep…up……with…pace….of….life. No….time…to….say….”lavalier”.

It’s the lavallier microphone thing. Just clip the damn thing on your clothing, or buy a proper hand held microphone.

It makes me wonder about how people in some countries are called by their last names wich are related with their professions: mason, smith, miller, taylor, wright, baker, carpenter, potter (hey Harry), spencer, etc etc.

People inherited the last names because they inherited the craftmanship. It was a family business after all. For the same reason, the man-centered society required women to adopt the husband’s name, instead of their own.

For me its funny how in Iceland the last name is mostly “the son of …” or “the daughter of …”. In this case marriage does not change the last name. Goodluck searching for relatives.

That’s why the most popular app in Iceland is an app to see if you are a relative. You don’t want to accidentally start a family with your cousin without realizing. They have a small population so that risk exists and not all families are close.

You could allow for migrant workers to come in. There’s millions of Pakistanis eager to make money and share their culture with Europeans.

But then you’d have uhh, millions of Pakistanis. I think the app is good enough.

John Handcock wad a ……?

Not really, as I’ve seen the same myth on more traditionally female crafts too, as they are still ‘the last craftsman’ of this particular traditional legacy sort.

Also in English Craftsman is just somebody who crafts, not really gendered by definition of the word, though now so often CraftsWoman or CraftsPerson would be considered acceptable. Like so many other terms for a profession they just happen to be a worker of the species man/huMAN and the word that encompasses that idea so often is a portmanteau of “job title” and “Human” (though if that was the intention when the job title was created is rather more ambiguous).

Linguistic history that leads to a language like that can I’d suggest justifiably be called sexist, but correctly using the work craftsman in relation to the fairer sex or now any one of the who knows how many rather less biologically correct genders there apparently are that happen to be talented craftsman is not. If anything its elevating them by inclusion with the elite not segregating them – as they are of the level they are worthy of being really called the craftsman, rather than the apprentice, journeyman, bodger etc.

That’s patronizing.

If the species is collectively called “man” in order to say that a “craftsman” is just a crafty member of the species, then logically “human” and “woman” become distinct subcategories. The very language you speak contains the implicit notion that women are not human.

The etymology of “woman” is from the Old English “wifman”, which is the combination of the words “wif” and “man” for “wife” and “human”. The male equivalent to ‘wif’ is ‘wer’, from whence we get words like “werewolf” – literally man-wolf. Linguistic drift (and probably laziness several centuries ago) has caused the meaning of ‘man’ to shift but ‘woman’ to stay the same. I’m all for railing at the patriarchy, but let’s keep our etymology straight.

I think it’s a sign of a civilization’s success and abundance (life has become so easy and one need expend so little effort to provide for basic needs) that people can instead focus on dictating to others what words they are allowed to use in communication.

It’s also sign of its decline.

And to think… I was worried that someone would fail to notice the striking sexist notions in patriachal narratives.

Maybe in this narrative it is less patriarchal, but conservative and stereotypical, which parallels to Jenny’s notion of resting yet once more the cliche of “The World Ain’t What It Used To Be”.

Sure it is reproducing the narative, with all sexism and gender roles. Does a disservice to all sexes and genders.

I saw youtube advertising the same video that I think inspired Jenny to write this, and was thinking about how the first movies of an nc swiss lathe shooting out a perfect finished bolt five times a second must have seemed like absolute magic in 1948, like the height of craftsmanship.

There was an interesting article in The New Yorker a few years back about how the cost of manufacturing clothes had dropped to nearly zero, so the only difference between a decent t-shirt and a decent t-shirt that shows everyone that you’re willing to spend $50 on a t-shirt is that the latter has a big DKNY logo on it, and that’s what you’re paying for over the $3 in materials, and that’s why IP law exists, and as a result, the people who need to really show off their wealth don’t buy mass market mass produced perfect clothes, they get someone to hand-sew it for them. Surgeon’s scalpels aren’t handmade by some Living National Treasure in Kyoto, they’re mass produced for perfect repeatability, and the people buying knives from the living national treasures are doing so because of desire. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course. What else is life for but getting something you REALLY, REALLY like? But the only place that hours spent in making something is a quality metric is in process-oriented art. (I say that as a person who makes process-oriented art.)

Trying to learn and gain some sense, so you’d be able to differentiate that which is truly desirable and that which is just expensive for the sake of being expensive?

After all, you know what you really like, but why should you like it? There’s two answers. If you can explain it then it must have some utility, and therefore it’s not the true target of your desire. The object itself won’t satisfy you no matter how it’s made or what it costs.

The other answer is, you can’t explain it, which makes such pursuits irrational. You’re just compelled to do it, and while that is unavoidable it cannot be said to be the point or purpose of life. It’s something that happens, like rain. Why do you love that fancy chair? You just do.

There is a difference between a $3 shirt and a $10 shirt though, it can have thicker material and better coloring agent and such things.

But yeah those overcharging fake-fancy ones are silly, especially when you know they buy them in at a tiny fraction of the salesprice. But you do have to take into account the rent and heating lighting and wages that shop have to take care of. And of course in premium locations the rent goes up too.

I’m actually still surprised how some normal shops with very moderate clientele can run a shop every day and pay the wages of the people working there without running a loss.

In those cases, the choice of using less and worse materials, and doing the stitching in a sloppy way is intentional since the increase in cost for doing it properly is negligible. The true cost of both shirts is really under three dollars, but the cheaper shirts are made badly in order to sell you more of them, and to make the more expensive shirt look better in comparison.

Consider, the $15 shoes that are made of plastic coated cardboard are just has difficult to make as shoes made out of real leather or fabric, and the material cost either way is negligible compared to the labor and logistics costs.

They could sell you good shoes at pretty much the same price, so why then do they make shoes out of cardboard? Because they wear down and break faster, so they can sell you more shoes.

They likely are running a loss. Just externalized to the workers who cannot get another, better paying job. There is a reason for the growing household debt and associated negative net worth of the last decile or two.

But unfortunately there can also be no or minimal difference in quality. It’s very hard to get durable well made clothing now.

See also: the fellow (because it always is) sitting in the dirt in or near a shack in southeast Asia or India or Africa (because it always is) with threadbare clothes and no shoes, doing the most despicably dangerous activity that would make an OSHA clipboard wielder scream in horror, with no modern Western tools, and cranking out beautiful trinkets to be peddled on the Western market for pennies. All to appease the mighty Content Gods and their all-powerful Algorithm.

My father was a dental technician, with a title as master craftsman, owning his own workshop, and training apprentices.

I always deeply admired his dedication to a high standard of aesthetics and functionality of work: crowns, bridges, inlays, dentures, handhmilled telescopic crowns, real master works in machinery, and more. When he did his job well, selected the right teeth color, translucence shape of the teeth, and arrangement, you would not recognize them as artificial. He helped so many people to being able to smile again without thinking twice about showing their teeth. Before holidays, he would fix broken dentures, even on weekends and evenings. He would sit in his workshop until after midnight to finish his work, because people waited to being able to eat, speak, smile again.

He passed his knowledge and aim for not less then the best he could give to many young and sometimes not so young apprentices.

Would he still work now, I would have to get a camera and just document for a day what he did. Not unique, but quite worthy being put in front of the curtain.

Neatly forgetting that Japan is one of the last places in the developed world that truly appreciates craftsmanship and expert knowledge of a subject and skill.

And one experrt time served bloke in a shed can still fulfill contracts based on utter precision vs cheapest it’ll do.

To the point where diy skills are utterly lacking as culturally its almost wrong to do so.

To what level ?

Compare redbull soapbox entries in Japan to any other country in the world.

They have access to cheap Makita tools, no wonder they’re built better than German ones build with Parkside crap from Lidl.

Talking about cheap, this sounds like cheap excuses.

Maybe it’s more a case that people in Germany with skills don’t bother with redbull soapbox stuff. Maybe it’s a societal thing.

I often see things on the internet, including HaD itself, where you just know there are very skilled and knowledgeable people who could easily do where all the rest of the internet are struggling and groping in the dark. And those people that could do it easily are just not interested in such fun-and-games and they work in businesses or research labs doing advanced stuff that keeps them busy and keep them challenged enough.

Sure, parkside isn’t the absolute best and some things aren’t built right. But my battery powered angle grinders are epic. The upgraded battery powered drill is epic. I got a whole collection of parkside tools and 10 batteries. I’m using parkside tools every single day and I’m happy with it.

I’m going to take issue with that description of Parkside tools. My hackerspace buys them to test if a tool is really heavily used, the idea being to replace them with Makita etc if they break. The surprise is that often they don’t break despite heavy use. They may not be the world’s highest quality tools, but they’re not absolute rubbish and can even be surprisingly good. Harbor Freight, they ain’t.

I’ve been replacing my Makita (low end) with Parkside…..

Same reason I buy angle grinders for $20 a go. In quantity.

They dont last long enough to justify an $80 – it that isn’t going to last 4x times long.

But 4x $20 ones will long out last the $80 AND I’ve got four of them so I’m not switching discs when doing a job, I’m picking up the other one and saving time. And if one dies my project isn’t stalled mid way.

When they die, usually it’s the locking button first, they get converted to other duties – like making a power file, or a drum sander, or xyz.

All those YT vids on using “why has no one thought of that amazing tool” – it’s the graveyard for abused $20 grinders.

It was just a humorous comment, because you know, Japan -> Makita. I didn’t mean anything more beyond that. If they have a jigsaw that can do cuts precise up to ±0,25 mm then “surely” their soapboxes will be better than german ones built with chinese Parkside tool accurate to ±1 mm.

You’ve clearly not watched them then.

hint: they are god damn awful.

Terrible designs, basic, badly built, fall apart.

Usually all using the same basic wheels and materials. No ingenuity.

They focus on “cute” and ignore that it’s supposed to go down a hill.

Parkside tools are no worse than any other rebranded tool and that includes Makita low end tools.

The big difference is Parkside isn’t shafting you on batteries like Makita does (and others) where they brick the BMS due to charging issues where the cells are still recoverable.

Which is why you can buy China copy BMS’s on the usual suspects.

Shameful practises. Parkside dont do that.

Yeah, nah, there is a lot more to Japanese craftsmen than the material aspect that you can observe and you can’t discount that difference. In fact I’d say it was that philosophical/spiritual aspect of their life that gave them the humility to seek perfection in the production of simple things. Japanese life is still deeply seeped in this characteristic of mind. Seriously, you do not know what you do not know. Oddly enough I came to this awareness because I was working in knowledge management for a very large defense contractor. We were trying to capture this craftsman’s spirit because we could see that there was more to what could be found in books and we were seeing a “last generation” of skilled workers fade away. Please take the time to consider what I am pointing out carefully. I do not seek to put people down and say they unworthy, rather I want them to see what it takes so that we can return in part to that greatness.

Great essay!

One skill from the middle of England that is (almost has) disappeared is the artistry that went into making pretty dishes. Royal Dalton and Wedgewood and others don’t get much demand any more for new patterns so the artists they used to employ have pretty much all been let go if they hadn’t already retired.

The skill that these people still have in their hands even though most are over 80 is astonishing. But they aren’t in tin sheds in Japan.

I’ve seen plenty of this sort of gawping content about people in England too (thatchers, makers of lace, Tim Hunkin). It’s not anything about Japan in particular, except that it’s easier to exoticise Japan.

And that’s the thing, this genre is only interested in presenting craftspeople as exotic others – they must belong to some distant culture, or lost past, or hermit lifestyle, because the intended lesson is that you, the viewer, will never make a living this way. It’s capitalist Sunday school, which is why so much of it comes from places like Bloomberg or the FT.

The truth is craftspeople are everywhere, and arise spontaneously in our millions with each new generation. We should celebrate this, and recognize that when a granny makes a crochet blanket, that’s more valuable than what Musk or Ellison do.

I guess you just highlighted the main problem with ‘online’. We have as a society lost the ability (if we ever had it) to network and find people who can help us make what we need.

I’m thinking of some blog posts of a man repairing pre-great-war vehicles and he would make a mold of a part and just send it off to be cast in iron. How would you even begin looking for that online? I mean as a decent service, not a boutique $$$ or £££ thing. Like recurving your truck springs. I know there is a place that will do it for $50 with new bushings installed. But I have no idea where to even start looking for them.

The internet has made it seem like we are a couple clicks away from anything. And if it’s Temu junk or AI slop I guess they are correct. But the solution is not wide-eyed personalities ‘re-discovering’ the way thinga were made for the last 200+ years.

Not sure what the solution is, but I would hazard a guess that Tim Hunkin isn’t far off. If you never have go watch his series “Secret Life of Machines” and then his recent web series where he has updated it with maker stuff like Addressable LEDs!?! Man’s a national treasure (not sure why I typed that, I may have a DNA test that is almost 40% British, but I like my father and mother was born in California. Almost 60% Bavarian too, so you can guess how well I fit in. NorCal BTW, rice fields and orchards).

Also a big fan of Howee’s machine shop, he always has a lot of neat stuff going on.

“The World as it is today”? :)

Isn’t it usually men who make stuff, though? It’s descriptive.

Good question. I’m curious how the world would look like if the roles were switched.

Who knows?

I mean, some fathers are more sensitive and better at raising kids than the mothers, too.

No matter how the experiment would end it would be something to learn from.

https://users.cs.utah.edu/~elb/folklore/mel.html

Sad thing is, that the quality of local “craftsmen” has gone down the drain in such a way, that I (a mere software guy) does better masonry than the “craftsmen”

heh don’t mistake laborers for craftsmen! A lot of construction tasks wind up being done by completely unskilled labor. Unfortunately spread all across the spectrum of bid prices and contractor size, so you can’t just filter out the low bid or jack of all trades. The craftsmen still exist, it’s just easy to find fools instead.

You’ve bascially described the negative space around “this market was taken over by cheap imports from China.”

Why don’t you get screws, springs, or other basic widgets from your local small-shop manufacturer? Because there isn’t one. If there was, you wouldn’t bother to find them or buy goods from them because it’s easier to find something online and have it shipped to your door.

Of course that level of commoditization takes away any choice beyond “pick an item from the menu we give you”, so the entire concept of the widget as an object that can be designed and optimized for a specific purpose becomes ‘stupid’. Standardized parts are based on good design principles that allow general application, and most designs have other paramaters that can flex to accomodate them.

There are rare cases where a widget actually matters though, and you need something beyond ‘standard component made from whatever metallic cheese substance you get in a box from Lowes’. Then you have to find a widget maker.

The companies that crank out shwag will start by asking about MOQs in increments of 10k units, how many you’ll order per year, and how many years the contract will run. If the total isn’t large enough to spin up a new production line, they won’t even answer. So you need a small shop capable of hitting specific design targets.. aka: a craftsman.

Nobody makes a business plan hoping to becoming a niche-market widget supplier, so the craftsman will probably be a generalist who developed a critical mass of reputation for being good at making that kind of widget. They probably have ongoing business with a couple of larger companies that don’t want to develop widget-making as an in-house core competency. That takes time, and a side effect of, “we’ve gotten excellent results from this person for years” is that people get old. Other side effects include accumulation of specialized tooling and experience making mission-critical widgets, which improve the chance of getting more mission-critical widget business.

Add the fact that companies want to hire people with ten years of experience in technologies that were invented three years ago, and the old, established widget maker has natural market advantage over the young newcomer trying to make a name in the field.

The whole reason for going to the specialized widget maker is a need for something you can’t get with the standard materials and processes, so by a strange coincidence, the specialized widget maker invests in materials and processes you won’t find in mass production of parts you wouldn’t buy from them anyway.

Japan has a cultural tradition of respecting quality and expertise which extends to its business practices. Large companies will cultivate keiretsu of small suppliers with overlapping interests, and will assign value to supporting experts and elders. That’s in opposition to the “it’s trash by comparison, but it’s 2% cheaper, and lower spreadsheet number is better spreadsheet number” mindset that dominates the American MBA subspecies.

None of this is magic or mythology. Most of it is good strategic asset management if your requirements extend beyond “what’s the worst product we can sell at the highest margin?”

Can only assume this reflects the author’s search habits. I literally never see this sort of myth.