These days, most of the media we consume is digital. We still watch movies and TV shows, but they’re all packaged in digital files that cram in many millions of pixels and as many audio channels as we could possibly desire.

Back in the day, though, engineering limitations meant that media on film or tape were limited to analog stereo audio at best. And yet, the masterminds at Dolby were able to create a surround sound format that could operate within those very limitations, turning two channels in to four. What started out as a cinematic format would bring surround sound to the home—all the way back in 1982!

From The Silver Screen

Dolby’s surround sound efforts were not initially aimed at the home, but at the cinema. Classically, movies were distributed on 35 mm film with a mono soundtrack encoded optically alongside the image frames themselves, with an upper frequency limit usually topping out at around 12 kHz. By the latter half of the 20th century, this was considered quite poor compared to the much richer stereo sound that filmgoers would otherwise be used to from media such as vinyl records or tape systems. A great deal of research and development was pursued by the industry, with all manner of alternative formats envisaged to make stereo sound viable for movie theatres.

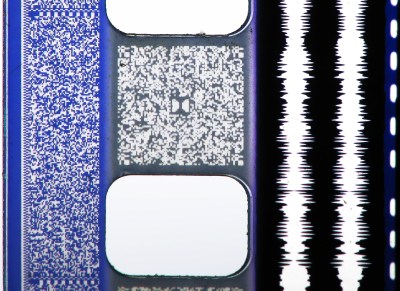

Dolby’s solution was to team up with Kodak, finding a way to squeeze two optical audio tracks into the space where there was only one previously. Dolby’s well-developed noise reduction techniques came in handy in this regard, making the most of the lesser dynamic range available in the compressed space. In 1976, the technology became known as Dolby Stereo, or Dolby SVA, for Stereo Variable Area—the latter referring to the fact that the sound amplitude was encoded by variations in the area of transparency in the film’s audio track.

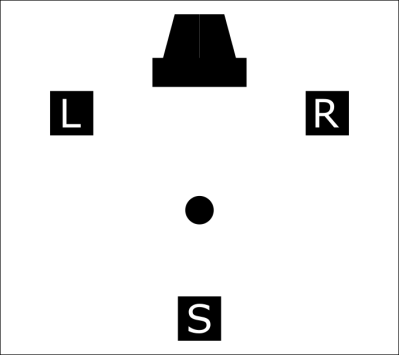

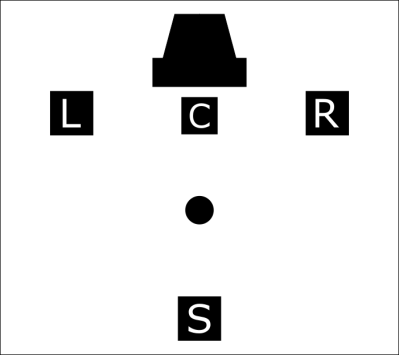

Dolby had successfully figured out how to distribute full stereo audio with 35 mm film prints. However, the work didn’t stop there. By applying similar techniques to those used in the burgeoning quadrophonic sound market, Dolby was able to create a rudimentary analog surround sound system. This was achieved with the use of a phase-matrix system, which could encode four channels into two stereo channels—left, right, center, and surround, with the latter sitting behind the viewer. A decoder would then split them back out to four channels for playback. This was achieved in a way that allowed the same stereo audio to be played back on regular stereo or mono systems without adding noticeable interference or noise.

In Dolby’s system, when producing the stereo soundtrack for a film print, the encoder would deliver audio for the left speaker directly to the left channel (L), and audio for the right speaker directly to the right channel (R). The center (C) speaker audio would be fed to both left and right channels equally, albeit attenuated by 3 dB. As for the surround (S) speaker audio, this would be attenuated by 3 dB, bandpassed from 100 Hz to 7 kHz, and then routed to the left and right channels, but with a phase shift of +90 degrees and -90 degrees, respectively. This method meant systems with only stereo or mono playback could play the same audio seamlessly as a two-channel or single-channel mix without issue. The surround content would cancel out, and the viewer would just get a regular stereo or mono output.

This method created a stereo recording which could then be decoded back into four channels, albeit not completely discretely—you weren’t getting four distinct channels, so much as two distinct channels with a center and surround channel derived from them with limited separation. In particular, the center channel was often used to deliver dialogue as if it was coming straight out of the screen, while the surround channel was used for more diffuse effects.

Dolby’s cinema audio decoders worked by using some basic logic circuitry to give priority to the channels that had the highest signal level by attenuating the others slightly, which created some additional separation. A time delay of up to 100 ms was also used on the surround channel installed behind the viewer. This ensured that sound leakage from the the left and right channels didn’t confuse the viewer by appearing to come from behind, thanks to the precedence effect—where the human auditory system perceives direction of a sound based on the first arriving waveform.

Bringing It Home

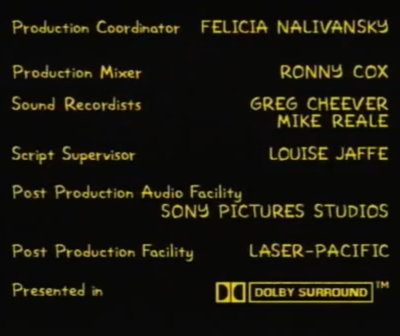

Dolby’s system was designed for cinema use, but it was by no means limited to such facilities. By 1982, with VHS and Betamax video cassettes started offering Hi-Fi stereo sound, it became entirely possible to deliver the same experience to home viewers in exactly the same way. This actually eased production of home releases for movie studios, which could simply reuse their existing stereo mixdown from the theatrical release. This technology was marketed as Dolby Surround. It came with some simplifications, using only passive decoding and most notably eliminating the center channel. This allowed home decoders to be cheaper, instead just turning the stereo audio into left, right, and a rear surround channel. The latter channel was still limited to 7 kHz, and was recovered by taking the difference of the left and right channels. This only provided separation of as little as 3dB between the surround and other channels.

Things would improve just a few years later in 1987, with the advent of Dolby Pro Logic decoders. These used so-called “steering logic” that was more similar to the decoders used in original theatre implementations. This involved decoding the stereo tracks into four channels, and monitoring the dominant prevailing direction of the sound. Based on this, the amplifiers for each of the four channels (L,R, C, S) would be varied to create greater separation of up to 30 dB between channels. For example, if the sound was loudest on the left channel, the other channels might have their output lowered to emphasize the effect. This method involved careful control of the amplifiers to ensure total output levels remained relatively constant to avoid audible discontinuities. Dolby would continue to iterate on the system, later developing Pro Logic II decoding in 2000. This was designed to scale Dolby Surround content to suit 5.1 channel systems that were becoming popular with the rise of DVD and more advanced home theatre systems. Pro Logic IIx would follow soon after, doing the same but with 6.1 and 7.1 systems.

Dolby’s engineering trick was intended to make multi-channel surround sound possible in an economically and technically viable way, for both cinemas and home viewers alike. It largely succeeded, particularly because of its all-around compatibility. Movie studios and TV stations were able to sell or broadcast Dolby Surround content perfectly easily without impacting the larger install base of viewers that only had mono or stereo speaker setups. The only requirement was to spend some extra time finessing the mix at the encoding stage, something most were already doing for theatrical releases anyway. Many people never realized that their VHS tapes or Laserdiscs had surround sound capability, because they never invested in a decoder and a multi-speaker setup at home. A huge range of home media came complete with surround content from the 1980s onwards, but a lot of consumers didn’t notice.

Matrix decoding systems like Dolby Surround eventually fell out of style as technology moved on. With the advent of the DVD and other more contemporary digital formats, it became very simple to simply include extra audio channels in the media itself. There was no need to try and mix four down to two channels and then expand them back out—you could just include four, five, or even more audio channels right in the original content. This had the benefit of providing complete channel separation. There was no decoding process that would leave your surround channels with content from other channels in them.

Dolby Surround is one of those fun technologies from yesteryear. It reminds us that a bit of maths and creativity can enable impressive feats amidst even quite restrictive technological limitations. We might not have to work that way anymore, but it’s always instructive to learn these lessons from our recent past.

My local theater regularly does classic movie screenings from original 35mm prints, and the all-analog optical sound is surprisingly decent. But they also occasionally get to screen 6-track magnetic sound 70mm prints, that’s a HUGE upgrade. Sounds as good as modern digital surround sound.

I would imagine that any modern film projector would be able to decode the Dolby Surround track (if the film has no SDDS, Dolby Digital or DTS option that is) and play it back on whatever surround sound setup that film projector is connected to.

A decent number of video games in the pre-HDMI era supported analog Dolby Surround encoding. Back in the day I had my GameCube hooked up to a 5.1 surround system, and despite only having the stereo RCA outputs, games like Mario Kart Double Dash had fantastic surround effects and made great use of the rear channels

As a videogame sound designer since 1993, we had a number of techniques for exploiting Dolby Surround. For cinematic cutscenes, we used the Dolby SEU4 and SDU4 units to encode and decode surround to the stereo tracks. For gameplay, the trick was usually to do a phase flip on sounds that were intended for the surround channel. While not a true +/- 90 as the SEU4 would do, the net result of the left and right channels being 180-degrees out of phase was the same. Whether it was the left or the right channel that needed flipping in a particular situation depended on where the sound emitter was in relation to the listener, such as to the left or the right of the player.

On older consoles, such as the GameCube or the PlayStation, often all that was needed to invert the phase was to set a sound’s volume to a negative value. Generally, gain was just a floating point scalar applied to the sample stream, so negative values just inverted the waveform. No complicated DSP was necessary.

Thanks for the inside info!

Yes I remember the first Playstation on my projector and 5.1 system playing Aliens with the face huggers crawling around behind me. And who can forget the New Pants Required moment when you re-open the Main door in Resident Evil.

Reminds me of the DOS era and the Sound Blaster 16’s ASP chip.

It could be used to support QSound in games (TFX by Ocean).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sound_Blaster_16

Other ISA bus soundcards that time had certain 3D sound effects, too.

The PAS16 had one (as mixer setting), as had the Adlib Gold with the optional Surround module.

The latter could be controlled in software, providing a more realistic 3D sound.

It’s not hard to experiment – the equations you need for various matrix surround methods is on Wikipedia. You could just use those to encode your audio to play back in surround or take audio and decode it.

The thing with Dolby Surround is it’s also able to decode a stereo track into surround even if the original tracks were not – the center decoder used audio that was going to come from the center anyways in the stereo image

Quadraphonic sound was already around in the 1970s on vinyl and 8 track tapes.

Indeed, Dolby was quite late to this party. Ambisonics, QS, SQ and other phase encoded matrixing options came decades before, and are still easily decodable.

The point was getting multichannel audio out of only two channels on the existing film and maintaining compatibility with existing audio systems so Dolby was not “late to the party”. Dolby decoding is still a feature on every home theater receiver, quadraphonic not so much. Quad was unsuccessful because you needed all new content and equipment at the same time.

Quad was encoded onto LPs.

Don’t recall the gory details, just the detail that the encoding frequency for quad was some fixed int divider away from the sampling frequency of CDs…

Early CD users were expecting quad CDs, but never happened.

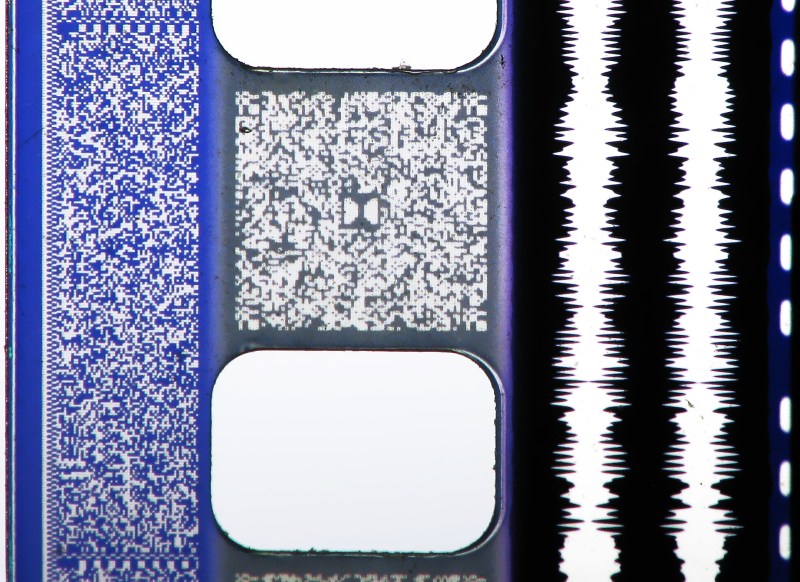

The dashes visible on the far right side of the film frame are the timecode for DTS. They’re used to synchronize a CD-ROM containing six channels of digital audio (5.1) with the film. A single print can support up to six playback formats: three digital – SDDS, Dolby Digital, and DTS, and three analog – mono, stereo, and Dolby Stereo.

One thing interesting about Dolby Digital is how they stamp their logo right between each sprocket hole.

I once heard Perspecta Directional Stereophonic Sound at the futurist Cinema in Birmingham. Can’t remember the film but was very impressed with the system. Were there any speakers in the Cinema or was everything directed to the screen. I’d love to experience it again but I think it’s a forlorn hope.

How hard is it to detect Dolby Surround audio from a stereo track on content? I’m just wondering if I have (encountered) content that could be “3.0” instead of just 2.0 on my surround system.

We used to do this “down-and-dirty” with a crossover network.

For quite some time in the mid 2000s, i’ve had an SQ quadraphonic decoder in the living room audio system. It was also connected to the TV. While SQ quad is not fully compatible with Dolby’s various surround systems, it absolutely did pick up on certain movies’ surround sound. I remember the thing just being on by default, and suddenly when watching a movie the helicopter’s sounds in a movie like Apocalypse Now or something came from behind. That was pretty spectacular when you didn’t expect it.

Long before Dolby, in the 50s, the Cinerama system provided discrete surround sound. In addition to the 3 slaved 35mm film projectors, there was a 4th with 35mm magnetic tape. It was an awesome system, way ahead of its time.

It was New Years Eve 1994 and some lads probaly 18 years old and eventually studying sound engineering arranged a truely Hi-Fi movie screening for a party in our village. It was the original Star Wars Trilogy. I do not remember which video format they used, VHS or Laserdisc or maybe Betamax, but I do remember they had a video projector and 4 channel setup and explained it to me. I was a like 15 at that time and understood the center mix, but the phase shift mix for the back effects was close to magic to me. Now after reading this article, I could explain it by myself, thanks for the great work.

Btw, the sound was not less then amazing to me as was the party!

I still own an NAD AV-716 surround sound receiver (Dolby Surround Pro Logic 4.1). I never upgraded because most of the stereo audio signals are in fact (unofficially) encoded in Dolby Stereo.

The NAD receiver has an analog audio chip decoding stereo into Dolby Surround Pro-Logic.

The NAD receiver in combination with 5.1 THX Teufel speakers is mindblowing. Classical concerts on TV are amazing, you hear every little detail where it supposed the be and that not only in the sweet spot. Heck even outside the surround setup.

All of this discussion reminds me of the short-lived era of quadraphonic sound – just music, with no video needed. I did a lot of experimenting with – and just plain enjoyable listening to – the Dynaquad system: https://obsoletemedia.org/dynaquad/

It wasn’t as impressive as its more advanced competitors, but it could still sound great and it had some serious advantages. First, in its simplest form its only equipment cost was that of two additional speakers. Second, it was capable of making even regular stereo recordings more engaging and exciting. I never evaluated the ‘fidelity’ aspect, but I certainly blissed out to Dark Side of the Moon revolving around the room. Later on I played around with using op amps to create the sum and difference channels, with two stereo amps to drive the four speakers. Now that I’m reminded of it, I may just throw together a couple of op amps and look for extra dimensions in some of my 3TB-or-so of music.

Sadly, very few recordings encoded in Dynaquad were ever pressed. The only one I ever had was The Beach Boys album Surf’s Up – but by the time I got that I no longer had a Dynaquad setup.

We had NICAM stereo on broadcast tv PAL standard for many years in the UK, with similar encoding systems across Europe and IIRC Russia too. My VHS did NICAM decoding for recorded tv programmes. Dolby came in with pre-recorded VHS films.