It is well known that pictographic languages that use Hanzi, like Mandarin, are difficult to work with for computer input and output devices. After all, each character is a tiny picture that represents an entire word, not just a sound. But did you ever wonder how China used telegraphy? We’ll admit, we had not thought about that until we ran into [Julesy]’s video on the subject that you can watch below.

There are about 50,000 symbols, so having a bunch of dots and dashes wasn’t really practical. Even if you designed it, who could learn it? Turns out, like most languages, you only need about 10,000 words to communicate. A telegraph company in Denmark hired an astronomer who knew some Chinese and tasked him with developing the code. In a straightforward way, he decided to encode each word from a dictionary of up to 10,000 with a unique four-digit number.

A French expat took the prototype code list and expanded it to 6,899 words, producing “the new telegraph codebook.” The numbers were just randomly assigned. Imagine if you wanted to say “The dog is hungry” by writing “4949 1022 3348 9429.” Not to mention, as [Julesy] points out, the numbers were long driving up the cost of telegrams.

It took a Chinese delegate of what would eventually become the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to come up with a method by which four-digit codes would count as a single Chinese character. So, for example, 1367 0604 6643 0932 were four Chinese characters meaning: “Problem at home. Return immediately.”

Languages like Mandarin make typewriters tough, but not impossible. IBM’s had 5,400 characters and also used a four-digit code. Sadly, though, they were not the same codes, so knowing Chinese Morse wouldn’t help you get a job as a typist.

A few years ago I was reading about alternate number systems. Humans , of course, are typically base-10 machines (no doubt because of 10 fingers) while computers are base-2, where the digits zero and one are conveniently represented by voltage-on and voltage-off. But what are the relative merits of x-symbols vs y- digits?

If you have a small symbol set (like binary) then the number of digits you need to express a given quantity goes up. Conversely, you can reduce the number of digits needed by increasing the number of symbols, but now you have a potentially cumbersome symbol set. It strikes me that these same principles probably apply to alphabets, and that pictographic systems like Chinese correlate to the latter case.

If I recall, mathematics say the most efficient balance between symbol set size and number of digits is Euler’s number… implying a symbol set of three. Indeed base-3 computing hardware would seem to promise improvements in power consumption and performance… but I wonder if similar math/logic applies to written language.

Culturally interesting perhaps, but 10’s of thousands of pictographs is not a practical way to navigate the modern world. My question is, what size would the most efficient alphabet be?

Ternary is fun, but seximal is the future!

I wonder if that article might be related to the crypto challenge in the next badge for HAD conference.

I don’t know why but the reply button to the main thread sometimes place the comment beneath another.

Is it not written, “Hexapodia is the key insight”?

I regularly use binary (computer stuff), octal, hex, decimal of course, base 12 (hours, time, eggs haha), and sexegesimal (time again, celestial nav hobby). Alternate base systems are more common than you’d imagine.

Time and eggs don’t use base-12, they use the same character set as base-10. You would need dedicated symbols to represent 11 and 12 for it to be in base-12. If you do in fact have distinct characters for your egg-counting, please share; that sounds fascinating.

is “⏰” symbolic enough?

That is wrong. Binary is base 2. Where is the dedicated symbol for 2? Base 10 is base 10. Where is the dedicated symbol for 10? ||. There, dedicated symbol for 11. Or you could use the letter “A” or more appropriately “L”. There is no rule against it. Don’t conflate how one thinks with how one writes.

“If you have a small symbol set (like binary) then the number of digits you need to express a given quantity goes up.”

Are you suggesting that using a larger base number system would make these morse messages shorter?

Not really. You would write it with fewer characters but you are still limited to just a dit or a dah in your actual sending so each of those characters would require more dits and dahs to be complete.

I guess you could say it’s still just base 2 at the hardware layer.

UTF8 already has a set of numbers allocated for Chinese, Korean, etc. Why invent yet another table?

A few years ago I was reading about alternate number systems. Humans , of course, are typically base-10 machines (no doubt because of 10 fingers) while computers are base-2, where the digits zero and one are conveniently represented by voltage-on and voltage-off. But what are the relative merits of x-symbols vs y- digits?

If you have a small symbol set (like binary) then the number of digits you need to express a given quantity goes up. Conversely, you can reduce the number of digits needed by increasing the number of symbols, but now you have a potentially cumbersome symbol set. It strikes me that these same principles probably apply to alphabets, and that pictographic systems like Chinese correlate to the latter case.

If I recall, mathematics say the most efficient balance between symbol set size and number of digits is Euler’s number… implying a symbol set of three. Indeed base-3 computing hardware would seem to promise improvements in power consumption and performance… but I wonder if similar math/logic applies to written language.

Culturally interesting perhaps, but 10’s of thousands of pictographs is not a practical way to navigate the modern world. My question is, what size would the most efficient alphabet be?

Oh, a “shocked face” youtube video. I’m definitely going to not watch it 🙂

But you do see the clickbait title or is that blocked too (that would really help).

about 20 years ago i had the insight that it is very easy to get things in the brain, but very difficult to get them out, so I started looking at all the info around me trying to get in: commercials, billboards, advertising, news, disasters. I stopped watching tv, listening to radio and reading the newspaper. if something important has happened, people around me will inform me. meanwhile i found commercial free radio (soma.fm) and youtube happened.

of course youtube became worse and started showing commercials. then the majority of the content itself went down hill.

now my filter list:

the X best.. (insert number)

X ways…

why…

you will not believe…

the best/worse/fastest/slowest/longest/shortest/cheapest/most expensive/smartest/stupidest…

titels containing: this, they, shocked, brutal, amazing, level (next/another), destroyed, karma, karen, disaster.

A filter plugin ignoring these words or parts of phrases should be possible.

and the list is growing day by day. titles starting with a number were one of the first filters i mentally filtered out a few years ago. lately AI generated content.

Of course shorts are also filtered away by a plugin. but then again, youtube still remains the biggest faeces hole around.

(is this allowed? As an european im not sure what allergic reactions people in the usa have to specific words describing genitalia or stuff the body has to get rid of. must be something to do with that “free speech, but” thing. sorry my ignorance)

but we digress.

the coding way the chinese typewriter used is very smart. but i have no idea how you would use this written language as im only familiar with the 2 times 26 letters from the alphabeth with some extra characters.

yes, for example

danooct1channel10k dictionary, using 10k worth of numbers is still going to be an insanely difficult memory issue for the operator imho.

I’m sure there is a good reason why they didn’t, but my first thought was why not use numbers to represent radicals? Radicals are the simpler characters that make up the more complex ones. When learning to write Chinese, children learn the simple ones, and then how to combine them into the more complex ones.

When entering text on a keyboard, one option is to enter the radical from the top left, then the one form the bottom right, and finally choose the complex character from a shortlist by entering a number. Seems like that would be a much more memorable way to handle Morse code too.

“I’m sure there is a good reason why they didn’t, but my first thought was why not use numbers to represent radicals? Radicals are the simpler characters that make up the more complex ones. When learning to write Chinese, children learn the simple ones, and then how to combine them into the more complex ones.”

Uh, yeah, no. That’s not how it works. Chinese characters are not made by combining radicals. And children learn whole characters first. Radicals are simply classifiers or headings, 部首 (214 for quite a while now but there’s no reason they couldn’t be more or fewer, and have been in the past).

Just to be super clear, characters are not “radical+radical+radical+radical…” = character.

This reminds me of the old telegraph code books.

Its mainly designed for telegraphy

Thousands of years of using such ineffective system of writing makes it nearly impossible to change it for something better. It is also interconnected with speech system, which uses pitch to change meaning.

Hard to solve.

Reminds me of nations which for similar historical reasons keep strange measurement units:) But they minimally united nice part of world with using simple and effective language with plus-minus adequate writing system. Thanks and go on!

It’s FAR from ineffective.

In fact, in some aspects idiograms are MUCH better than sound-glyphs.

Person-mountain-alone-teacher still has meaning, even without context.

Idiograms are incredibly good at convting general ideas and relational mapping.

You know how there is a running joke about how absurdly long Anime titles are?

“That time I fell into a hole and found myself in another world filled with dragons. Now I’m trying to find a way home before I lose my job at the convenience store and my girlfriend leaves me.”

That is a whole lot of ideas to come from a translation of 5-6 characters in the original title…

Chinese can be very semantically dense. In a book I used to have there’s a translation of a poem whose title in English is given as “Poetical Exposition on Literature”. The Chinese title transliterates as five characters: “Wen fu”. In Chinese, it’s just two: 文賦

yeah, this was an interesting insight when I was learning Japanese: because it shares some idiograms with Chinese, I can read a chinese recipe book and at least have some idea of what they’re talking about with absolutely zero idea of how anything is pronounced. I can see new kanji and say no idea what that is but I bet it’s something involving speech or communication, because I recognize the radical. It’s an interesting type of context harvesting.

(Of course English does something similar: you might not know what a rhino is but you have some guess that it might have an interesting nose area.)

1131 1344 7024 1639 1034 1129 1458 3010

In shanghai near the Bund is a great museum called the Shanghai Telecom Museum, on yan’an road. Must see for geeks, theres even a semaphore signal tower near it. While your are at it, visit the gutzlaff signal tower 5mins from there, a semaphore style weather info tower from the early 1900’s.

better question is where is simple (short) sample of dictionary in any language.

esperanto need 3K , simple basic english (using in other place uses english 8K)

meybe we make smalest dictionaty?

We should all switch to esperanto.

It was a thing by the turn of the century, I remember.

Some websites had an Esperanto version at the time.

Esperanto basically was seen as a new version of Latin language, as a world language.

From a political point of view it would be rather neutral, too.

English is being associated with western society, by contrast.

So it would make sense if a basic set of Esperanto would be thought worldwide in schools, maybe.

It would maybe build bridges about different societies, because it feels more like the true language of a free world.

Neutral? Hardly. Just as English evolved around British, then American/Canadian/Australian values (as it also guided those cultures), Esperanto was mostly based on Latin languages, still solidly rooted in the West, mostly Europe and South America (excluding indigenous languages), and largely excluding the thought patterns in Eastern cultures. Peoples’ thoughts are guided by what is expressible in their native language, and the language is adapted to their thoughts. It is a fool’s errand to come up with a universal human language. Which to be fair, wasn’t the purpose of Esperanto. Its purpose was to be a second language that would be easy for people (who grew up in European cultures) to learn, that others around the world could also learn, acting as an international trade language. The League of Nations, and later the United Nations adopted Esperanto as an intermediate language, so that each interpreter needed to know only their native language and Esperanto.

There is no reason for this to involve Chinese at all. The random number is directly representing a word there is no need to go through an intermediate character.

My Chinese is a little rusty but I’m pretty sure it isn’t one-character-one-word. There are plenty of words that are compound ie two or more characters linked together to make a word but like English here.

It isn’t. Each character changes meaning depending on context.

If you encode the word instead of the character, the same number could mean a number of different Chinese characters depending on what you’re trying to say. It’d mean you have to invent an “intermediary language” between Morse code and Chinese to turn the number into a word and then the word into a character, instead of just mapping numbers to characters and letting the reader decipher the meaning.

Reminds me of some vintage RTTY decoders of the 1970s and 1980s.

They could do Japanese RTTY with JIS encoding. Such as Tono Theta 777.

It mainly were models by Japanese manufacturers. The Japanese were big in amateur radio in late 20th century.

Yeah, Chinese telegraph code. I have a reference book on that. Realistically someone who knows 2,000 characters is literate but they did a thorough job. To speak about 50,000 is blowing smoke because that includes archaic and no longer used characters. 11,000 would be very impressive. My first dictionary which I still use was called the 5,000 Dictionary. Blue paperback. These days Unicode handles it: each character has its own number. Everybody calm the heck down, won’t you?

Lin Yutang invented a Chinese typewriter, I don’t know if that’s the one mentioned in the article.

4 number codes for letters? Sounds like it would be ideal to use with a one time pad.

Hey go after the guy who pissed on your cornflakes, not me.

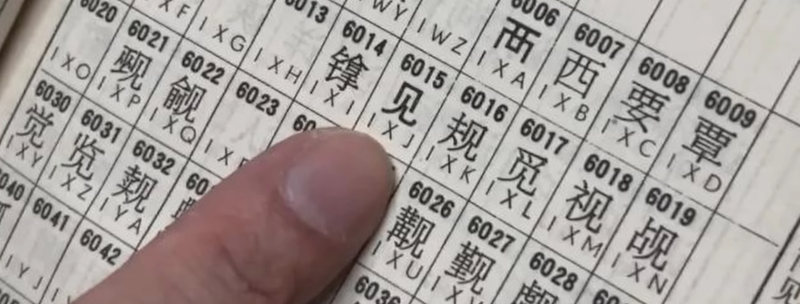

In the title image, it appears that each ideograph has a 4-digit number above and a 3 letter sequence below. Possibly because sending the 3 letters is shorter (but more prone to error) than the 4 digits, which are to some extent self-checking, since the number of dots equals 5 minus the number of dashes.

The three-letter sequences were introduced much later.

We don’t need anywhere CLOSE to 10,000 words to communicate.

1,000 is plenty for most forms of communication, if you are a masochist writing books for masochists…

Randall Munroe of XKCD has a book titled “Thing Explainer” that goes over tons of stuff using only the most common ten-hundred words. And he also explains the Saturn 5 rocket parts in the same style in an infographic titled “Up Goer 5: the only space car to take people to oher worlds”

Try using Pin-Yin.

Three letter codes would have allowed over 17,000 symbols, and since these would be letters, each letter is about 2/3 the length of a numeral, so the saving would be 3/4 * 2/3 = 6/12. Half the time to transmit a character. The person who suggested 4-digit codes not only didn’t know much about Chinese, but also didn’t know much about Morse code.

The language is Chinese. Mandarin is a dialect of the Chinese language. The language is not Mandarin.

I worked on this a few years ago using unicode to hex and back for JS8 with a lookup table. You can find my code here. I know it’s not “native” morse code but you might find it enjoyable or interesting. https://github.com/matthewshoup/Chinese_Unicode_CJK_to_hex_and_back_javascript

I’m not sure why this was necessary. Are those just in the UTF-8 encoding of the codepoints for CJK, or is this some other kind of encoding that the community has agreed on?