Learning something on YouTube seems kind of modern. But if you are watching a 1957 instructional film about slide rules, it also seems old-fashioned. But Encyclopædia Britannica has a complete 30-minute training film, which, what it lacks in glitz, it makes up for in mathematical rigor.

We appreciated that it started out talking about numbers and significant figures instead of jumping right into the slide rule. One thing about the slide rule is that you have to sort of understand roughly what the answer is. So, on a rule, 2×3, 20×30, 20×3, and 0.2×300 are all the same operation.

You don’t actually get to the slide rule part for about seven minutes, but it is a good idea to watch the introductory part. The lecturer, [Dr. Havery E. White] shows a fifty-cent plastic rule and some larger ones, including a classroom demonstration model. We were a bit surprised that the prestigious Britannica wouldn’t have a bit better production values, but it is clear. Perhaps we are just spoiled by modern productions.

We love our slide rules. Maybe we are ready for the collapse of civilization and the need for advanced math with no computers. If you prefer reading something more modern, try this post. Our favorites, though, are the cylindrical ones that work the same, but have more digits.

The production values are similar to older instructional films I watched in High School Physics class in the ’70s. A blackboard and talking head were all you needed.

“We were a bit surprised that the prestigious Britannica wouldn’t have a bit better production values, but it is clear. Perhaps we are just spoiled by modern productions.”

Or were spoiled by entertainment masquerading as education.

It’s missing the 1:30 intro, then announcing this week’s sponsor, then just enough runtime to qualify for a midroll ad, then some unrelated faff to do with channel news, reminders to like and subscribe, then a 2 minute teaser for the bonus content only available to paid channel members.

Back then we were interested in information content because it was bloody difficult to get. Nobody gave a damn about how pretty it looked.

Back then the difficulty was getting any information, so the key skill was carefully extracting everything. Nowadays there is a firehouse of data, so the key skill is quickly deciding what to ignore.

That’s the exact opposite.

yep, this was the time where close enough maxed out , today for what would have cost dollars in those times you can get something 5x as precise from Walmart for 99 cents in the school section

5 years ago I bought a 10 digit 4 line tabulating calculator 1.99 at the discount store

scales yes I can see the reason, side rules, its getting to be pretty rare in the useful range

Sorry, mate, I seriously doubt you can still get a slide rule anywhere, let alone at Walmart, let alone one that is precise, llike, at all.

Ah, you were talking about pocket calculators. The cheap, gimmicky ones (business card sized) were a pretty common thing to be thrown at business customers in the 80s. How may digits of precision do you even need in everyday life? I would consider three significant digits and a fourth one “close enough” to be plenty good for most things. Say, you are talking about lengths and want to calculate your bike wheel’s circumference. You measure the dimeter at 705mm. Now you multiply by pi, and the calculator spits out 2214.822820780804233116163585212 mm. Let’s look at the number groups.

822 -> going down to um

820 -> that would be 820nm, which is the wave length of near IR

780 -> subatomic

804 -> atom nucleus size, or thereabouts, and I’ll ignore the rest

It is important to know where to stop with your calculation. And the initial number was probably not exact to three significant digits (also because tyres are squishy).

Is the skill useful? Yes. It helps having a clue about orders of magnitude, the exponent part of the number, and which one to expect. Understanding the maths behind it also helps (well, it helped me). And at some point I realised that most problems I faced at university were either proofs (no calculator required), simple calculations (head or slide rule), or required me to write some code.

Check the Goodwill auction site. Plenty there.

I’ve played around with a few antique slide rules I’ve bought on ebay, etc. But that is usually good for one or two decimal places. I prefer to (play around) with a book of logarithms and my Odhner and Remington Rand, both of which I restored as a side to my antique typewriter restoration hobby.

Did you document the Odhner restoration anywhere? For example, did you use any oil ,and if so, what type?

I have one working Odhner, and one partially working Muldivo Mentor

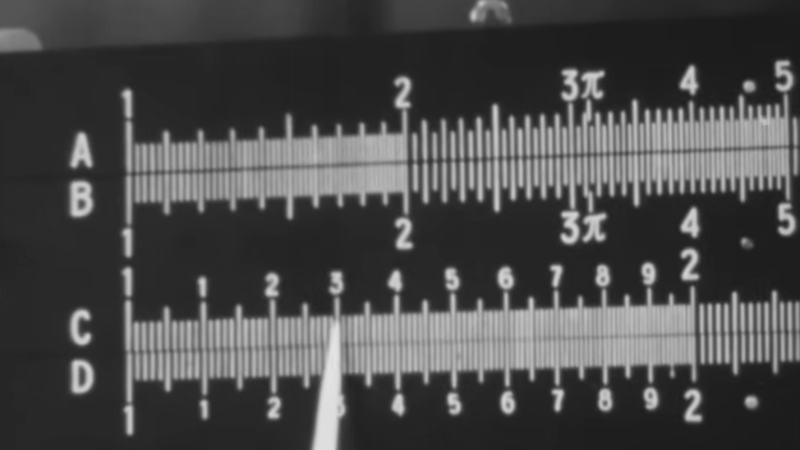

ABCDKLST are the easy scales, the ones everyone uses. I never used the folded scales, though I understand how they work. My hat is off and I will bow deeply to anyone who has routinely used the SH, TH or LL scales. Those are for hard-core calculations.

For anyone interested in slide rules in the UK there is a large collection in The National Museum of Computing on the same site as (but separate from) the Bletchley Park museum.

Yes; their pair of Fuller Calculators inspired me to get some. Many other interesting calculators too.

Everyone should go to TNMoC; the staff and volunteers really know their exhibits. (“Would you like to have a look at the schematics and see how it …..”)

The chaps who gave the talk on the Bombe gave a lot of detail and stayed on after their talk to answer questions. Did you know that when the machine steps the wheels to try another combination, it moves what would be the most significant ‘digit’ on the encoding wheel first. This eliminates a lot of false ‘stops’ quickly.

As an aside, when I was learning about computers in the late 60s, I often wondered why there were no serious history books or articles. The very existence of BP and what it had achieved was still classified, of course.

The work of the devil!