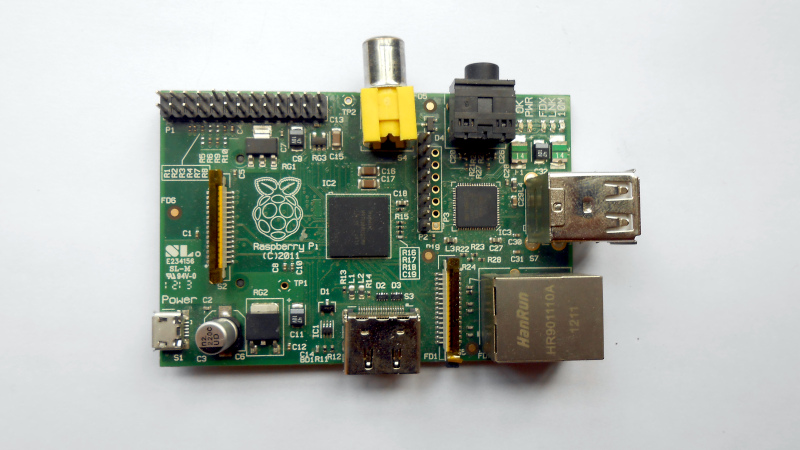

If you’ve ever experimented with a microprocessor at the bare metal level, you’ll know that when it starts up, it will look at its program memory for something to do. On an old 8-bit machine, that program memory was usually an EPROM at the start of its address space, while on a PC, it would be the BIOS or UEFI firmware. This takes care of initialising the environment in both hardware and software, and then loading the program, OS, or whatever the processor does. The Raspberry Pi, though, isn’t like that, and [Patrick McCanna] is here to tell us why.

The Pi eschews bringing up its ARM core first. Instead, it has a GPU firmware that brings up the GPU. It’s this part of the chip that then initialises all peripherals and memory. Only then does it activate the ARM part of the chip. As he explains, this is because the original Pi chip, the BCM2835, is a set-top-box chip. It’s not an application processor at all, but a late-2000s GPU that happened to have an ARM core on a small part of its die, so the GPU wakes first, not the CPU. Even though the latest versions of the Pi have much more powerful Broadcom chips, this legacy of their ancestor remains. For most of us using the board it doesn’t matter much, but it’s interesting to know.

Fancy trying bare metal Pi programming? Give it a go. We’ve seen some practical projects that start at that level.

Well, this is close to useless – he tells us three times that:

1) The GPU starts up from either internal ROM or external EEPROM, while the ARM cores are held in reset.

2) The GPU reads config.txt, initializes all of the hardware, and finds the kernel.

3) The ARM core runs the kernel.

Yeah, I just figured everybody needed to see that one more time.

The linked HaD article on bare metal programming the Pi may actually be useful, though. I don’t know how I missed that the first time around.

I found the article informative and concise, really good :-)

It’s also closed source (with Broadcom not providing any documentation) and highly privileged. A sort of Intel Management Engine for the pi. There was an attempt to implement an open-source boot firmware, but that effort petered out: https://github.com/christinaa/rpi-open-firmware

Well, it may not be ready for prime time, but that page looks like a treasure map to me. Not that I’m ready to do that kind of work; the Circle project https://github.com/rsta2/circle looks more like my speed, since it shows you how to build a “kernel” (i.e., any program you want to run on an A7, A53, or A72 core in lieu of a Linux kernel) that the standard Pi firmware will boot. I don’t have time for it right now, but it’s in my notebook.

Circle is an amazing effort. Rene made serious commitments over many years to bring a solid top notch bare metal solution to the Pi. I forked and used it to create my Looper https://github.com/phorton1/circle-prh-apps-Looper which is now part of the teensyExpression3 pedal/architecture https://phorton1.github.io/Arduino-TE3/#home.htm. Endless kudos to RSTA.

Thanks for this link, I wasn’t aware of this project! It’s perfect as it opens the way for fast booting (<1s) network audio devices on the cheap (COTS hardware) as opposed to bloated Linux stack just to turn UDP packets into analog audio (I don’t want to dunk on these OSS projects as they’re good for what they are) or overpriced proprietary FPGA/DSP-based devices (hello Dante audio) that do the same.

The “Traditional PC Boot” sequence is also wrong. The BIOS is definitely not the first code that executes on any modern PC! For instance, on Intel PCs, a small mask ROM executes on the Intel Management Engine core, which then loads and verifies a second-stage Management Engine binary that lives in the BIOS flash. As I understand it, ME does not initialize DRAM itself (DDR5 training is tricky business!), but it does initialize plenty of “uncore” components, and also does adjust some pad settings based on configuration options in the BIOS flash. Only after setting up those parts of the system, and loading in verification keys for Boot Guard, does ME then jump into the BIOS flash (which proceeds to set up DRAM).

This post says a bunch of contradictory things about how Pi’s secure boot is implemented. (It suggests that Pi’s secure boot does not provide immunity to malicious GPU firmware, but then says that that the chain of trust does start in the GPU. As it turns out, Raspberry Pi’s own documentation, page 5 shows that GPU firmware is also verified.)

Ugh. This post is very confidently written for how wrong it is.

But to be fair, the IME sort of is a whole embedded computer running Minix.

It’s thus more like an external debugger hardware that analyzes/manipulates the “PC” side at will.

Also, modern x86 CPUs aren’t true x86 anymore. They’re RISC-CISC hybrids that have a front-end that converts x86 instructions into nstive format.

Heck, even the 8086/8088 had microcode that performed things in software rather than in hardware! :)

The NEC V20/V30 line thus was more “native” at executing x86 instructions than the intel 808x line ever was.

Before the 80286 (maybe 80186) it didn’t even feature address calculation using dedicated hardware – it had to use the ALU for that (slow).

The Zilog Z80 likewise also used more hardware implemented functions, which made it more “native” at code execution than i8080/i8085.

I’ve worked for Intel as a subcontractor (Sii Poland) since 2018. Minix is not used anymore since at least 2023. They’ve replaced it with their own stuff.

Is that why when you change certain BIOS settings the system power cycles, because it needs the ME to reconfigure the board before bringing the CPU back up?

Not even a GPU, it is a VPU, a vector processor for video decoding.

“On an old 8-bit machine, that program memory was usually an EPROM at the start of its address space”. Commodore 64, old and 8-bit enough? The 6502 starts at the end-of-address-space. Just like 8086, 80186, 80286, 80386 and 80486 processors. And back in the commodore times commercial computers simply had ROM. Not EPROM.

The 6502, coming out of reset, would read the two bytes at FFFE and FFFF, to obtain a 16 bit starting address. (Just like the 68xx it evolved from)

The 68K, coming out of reset, would read the 32 bit word at address 000000 into the program counter, and the next 32 bit word from 000004 into the stack pointer, to get going.

Meanwhile, the 8088 approach was to just start executing at address 0000 in segment FFFF, which if you ironed that out to a flat 20 bit space, would be FFFF0, i.e., the last 16 bytes of the address space, room enough for a couple of instructions, e.g. a jump back to a more convenient location in the ROM.

Of course, in those days, the DRAM refresh usually took care of itself (baked into H/W), or was handled once you init’d your DMA controller. After that, you’d get your interrupt controller and interrupt sources under control, maybe init a video system, and then maybe go for a boot block from a disk.

The actual CPU took care of all of that. That was when processors were products, that tended to be very well debugged before they hit the market. But then, those products had on the order of 10^3 to 10^4 transistors, so “getting it right” was undoubtedly a lot easier than the situation today. With north of 10^9 transistors, apparently we’re stuck with CPUs that themselves need to be initialized (patched) before running, by some simpler, internalized CPU like the IME or what have you.

I believe you got the addresses reversed, but it’s interesting that 68k read the initial stack pointer from ROM. The only other architecture I know of that does that is ARM Cortex-M. It made writing startup code in C easier with no assembly required (pun intended). I wonder why this approach is not used more often.

“That was when processors were products, that tended to be very well debugged before they hit the market.”

FDIV says hi.

Well .. I didn’t say completely debugged, as that can only be approached asymptotically. Also, wasn’t FDIV in one of the Pentiums, around the turn off the century? Might have been part of the inspiration for the IME.

FFFC and FFFD for RESET. FFFE and FFFF are the IRQ interrupt vector.

It’s functionally same thing, though, I would argue.

The i/o and the inner mechanism is same, I mean.

The only difference is that EPROMs can be programmed by “burning down” an internal matrix of crystals by an external impulse.

Like blowing fuses or cutting diodes in a matrix.

The underlying technology between EPROM and a mask ROM is pretty much same, it uses same addressing logic and materials.

EEPROM is a bit smarter already. Flash technology then began to contain simple electronics in the chip package.

Then there are OTPs, one-time-programmables, which are EPROMs without an precious quarz window for UV erasure.

They’re still being produced due to being simple and cheap to produce.

Yeah i am with the other comments, this is non-information. When you have an open source project and you say “simplified” in your description of it, the assumption of the reader is that they can get to the bottom of it, that they can view the complication. But to view the complication on Raspberry Pi bootloader / firmware, you have to do an enormous amount of reverse-engineering work, hampered by Raspberry’s endless closed updates that give you little reward but always destroy all the benefits of your past reverse-engineering work.

The fact that this is a closed proprietary process should be front and center. The implication that Raspberry is the darling of the open source world is a deception that Hackaday has helped prop up. Even if you did it inadvertently, the harm has been done, and you need to work to fix this misconception, not silently allow it to continue. The summary of the linked content should be “a vapid overview of an extremely opaque process.” The fact that all the goodies are obscured should not be left as a future landmine for the reader.

I was genuinely surprised by the mess i met when i bought a raspberry pi, after consuming years of content here. This is not a hypothetical issue.

“Raspberry’s endless closed updates that give you little reward but always destroy all the benefits of your past reverse-engineering work.” A good reason not to reverse engineer the firmware/boot process then right? … As long as the outward ‘interface’ stays the same (maybe?), the followup application/OS should run. Also gives the vendor freedom to make changes on the back-end without having users complain about there code no longer works when vendor makes a change…

So, I guess I don’t see the ‘mess’ you are talking about. Why should we ‘care’ about the boot loader/firmware? Drop OS on a SD, SSD and your off an running with any of the RPI family. No mess. Or use Ultibo or Circle mentioned above and again, off an running on bare-metal. Fail to see, for a 99.99% of all users of the RPI hardware where the ‘mess’ is. Most of us don’t rewrite BIOSs in desktops/severs/etc. either right? — who wants to spend all the time re-inventing the wheel! We just expect them to get everything ready for the coder/user to take it from there. Ie. Just ‘use’ the board. A micro-controller on the other hand it is nice to have control from the ground up when needed at times… It really was fun back in the day when working with 68xxx/z80/6502 where it always started at a given address and up to you to set everything up (interrupt tables/memory access/etc.) before branching to the primary ‘use’ code. But that became a headache too as hardware evolved. So even then, we starting relying on BSPs when board architectures got more complex. Let the vendor do the ‘hard stuff’ so to speak… Let us concentrate on the ‘use case’. Time is money!

The time to worry is when firmware starts phoning home with your data and such, or won’t run without a internet connection, etc.

Thanks for article. Didn’t know that about the GPU to CPU process.

If you like to thnk of an OS as a closed blob that you upgrade atomically, then you don’t care if it’s open source or not. The problem is that Raspi is treated as a darling of the open source community.

If you try to hack anything on raspi then you very quickly run into a bad interface to a closed driver. AND THAT INTERFACE DOES NOT STAY STABLE. If you think the interface stays stable then of course you aren’t angry like i am. But i know it doesn’t, and i’m pissed off.

“The time to worry…” Okay, so how do you know when the firmware is phoning home, if it’s all closed? The most fundamental thing about open source software is that unless you can build and modify the code, you have no idea what it’s doing.

“Raspberry is the darling of the open source world”

“Raspberry is betraying the maker movement that gave them success”

yada yada claiming RPi is X and Y and Z when they never claimed to be any of the above. Typical HaD commenter rubbish.

The RPi is a device developed for a charity whose stated goal was to enable teaching computer skills to UK children. THAT’S IT.

Hobbyists were never their target market.

They were never Open Hardware.

They don’t exist to give you cheap hardware.

Don’t like it? Tough.

I’m straight up saying that hackaday is responsible for this misconstrual.

Interesting. I’ve heard from at least 2 former bcom employees that this chip was intended for a next-generation iPod video, not a set-top box.

If that’s true then it has fantastic power save features that are completely hidden behind their layer of proprietariness. Which would be even more insulting than the more plausible reality that it simply doesn’t have power save features because it’s a set top box.