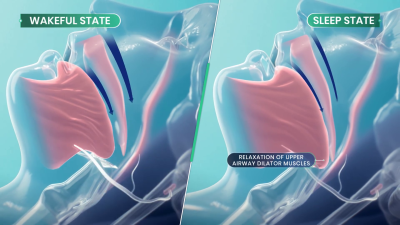

Sleep apnea is a debilitating disease that many sufferers don’t even realize they have. Those afflicted with the condition will regularly stop breathing during sleep as the muscles in their throat relax, sometimes hundreds of times a night. Breathing eventually resumes when the individual’s oxygen supply gets critically low, and the body semi-wakes to restore proper respiration. The disruption to sleep causes serious fatigue and a wide range of other deleterious health effects.

Treatment for sleep apnea has traditionally involved pressurized respiration aids, mechanical devices, or invasive surgeries. However, researchers are now attempting to develop a new drug combination that could solve the problem with pharmaceuticals alone.

Breathe Into Me

There are a variety of conditions that fall under the sleep apnea umbrella, with various causes and a range of imperfect treatments. Perhaps the most visible is obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), in which the muscles in the throat relax during sleep. Under certain conditions, and depending on anatomy, this can lead the airway to become blocked, causing a cessation of breathing that requires the sufferer to wake to a certain degree to restore proper respiration. Since the 1980s, OSA has routinely been treated with the use of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) machines, which supply pressurized air to the face and throat to forcibly keep the airway open. These are effective, except for one major problem—a great deal of patients hate them, and compliance with treatment is remarkably poor. Some studies have shown up to 50% of patients give up on CPAP treatment within a year due to discomfort around sleeping with a pressurized air mask.

Against this backdrop, a simple pill-based treatment for sleep apnea is a remarkably attractive proposition. It would allow the treatment of the condition without the need for expensive, high-maintenance CPAP machines which a huge proportion of patients hate using in the first place. Such a treatment is now close to being a reality, under the name AD109.

The treatment aims to directly target the actual cause of obstructive sleep apnea. OSA is a neuromuscular condition, and one that only occurs during sleep—as those afflicted with the disease don’t suffer random airway blockages while awake. When sleep occurs, neurotransmitter levels like norepinephrine tend to decrease. This can can cause the upper airway muscles to excessively relax in sleep apnea sufferers, to the point that the airway blocks itself shut. AD109 tackles this issue with a combination of drugs—an antimuscarinic called aroxybutynin, and a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor called atomoxetine. In simple terms, the aroxybutynin blocks so-called muscarinic receptors which decrease muscle tone in the upper airway. Meanwhile, the atomoxetine is believed to simultaneously improve muscle tone in the upper airway by maintaining higher activity in the hyperglossal motor neurons that control muscles in this area.

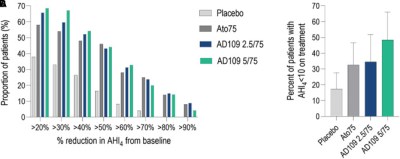

Thus far, clinical testing has been positive, suggesting the synergistic combination of drugs may be able to improve airflow for sleep apnea patients. Phase 1 and Phase 2 clinical trials have been conducted to verify the safety of the treatment, as well as its efficacy at treating the condition. Success in the trials was measured with the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI), which records the number of airway disruptions an individual has per hour. AHI events were reduced by 45% in those taking AD109 when compared to the placebo group in a phase 2 trial featuring 211 participants. It achieved this while proving generally safe in early testing without causing detectable detriments to attention or memory. However, some side effects were noted with the drug—most specifically dry mouth, urinary hesitancy, and a level of insomina. The latter being particularly of note given the drug’s intention to improve sleep.

Testing on AD109 continues, with randomized Phase 3 trials measuring its performance in treating mild, moderate, and severe obstructive sleep apnea. For now, commercialization remains a ways down the road. And yet, for the first time, it appears promising that modern medicine will develop a simple drug-based treatment for a disease that leaves millions fatigued and exhausted every day. If it proves viable, expect it to become a major pharmaceutical success story and the hottest new drug on the market.

As someone with sleep apnea, an AHI of 10 or less is not what I’d call good. The usual goal is 5 or less. That’s an average of 5 apnea events (obstructive apnea or hypopnea) per hour.

At that level, doctors will consider your apnea treated.

At that level, your sleep will still be fragmented and you will still have fatigue and other symptoms.

An AHI of 10 is far outside of what is considered good treatment. The range for mild sleep apnea is 5 to 15, so 10 still counts as having sleep apnea

I can see it used in parallel with APAP treatment to reduce the required pressure. I don’t see it replacing APAP, especially given the side effects.

From what I see on various forums and social media sites, a large part of the reason people quit APAP comes down to a few reasons:

Unrealistic expectations. Folks expect to wake up after using APAP, and feel like they’ve been reborn. Very few actually have that experience. For me, it was a long, slow, almost imperceptible improvement. It was most noticeable in that my consumption of Coca Cola went from 5 liters per day to stay awake and functional down to just drinking it now and then because I like the flavor. That was spread literally over years.

Insufficient support. Finding a well fitting mask is regarded as close to black magic. APAP machines are often delivered with the pressure settings left at the full available range. People need more assistance in properly adjusting the masks – much of the problem with masks isn’t that they don’t fit, it is that people don’t know how to adjust the headgear that holds it on your face. The wide open settings are are starting place, but not an adequate prescription. After a few nights on the wide open settings, you need to read out the full data from the machine and raise the minimum to a level that fixes most of the apneas. You also need to check for therapy emergent central sleep apnea (TECSA.) TECSA causes apneas that cannot be treated with pressure – you actually have to reduce or limit the pressure to keep TECSA from getting out of hand. TECSA does tend to get better with time, requiring periodic changes to the pressure settings to better treat the obstructive apnea as the TECSA goes down. All of that requires assistance from a trained technician or that the user takes charge of the treatment and changes settings as required. The user needs to have that explained and understand that it will all take time.

There are, of course, people with neurological or psychological problems who have difficulty with having something in contact with their faces while trying to sleep. Those folks need more assistance than the average user – and they don’t often get it.

There is more to acceptance, of course, but there’s only so much of it you can squeeze into a comment.

At any rate, I see the pills as helping with PAP treatment rather than replacing it.

As someone who recently learned of their apnea, I can relate. The machines are frustrating and I’m already on my second mask trying to get a right fit. I have what they call “mild” – which is anywhere from 20-30 AHI events an hour for me. I still have insomnia and narcolepsy symptoms. It’s definitely support, but not a silver bullet.

Should be combined with sleeping pill and ear plugs so no external perturbances will awake you.

I was sure insomnia would be a side effect, just from reading the method of action.

Aren’t the majority of sleep apnea patients overweight? It seems like weight loss would be a much better strategy than something which has a high potential to interfere with the quality of sleep.

I’m not overweight and have been using cpap for over a decade tyvm you insensitive clod

I am 5 feet 10 inches tall (180cm.) I had apnea back in the days when I weighed 130 pounds (60 kg.)

Overweight is one cause of apnea, but not the only cause.

Some of us were simply born with narrow airways.

According to some random web results, less than half are overweight. And AFAIK weight loss does not always fix sleep apnea even if weight gain had originally triggered it.

not only, person with Pierre Robin syndrome are also impacted by apnea. though not sure if this drug could help, as it is more genetic/physiologic.

Depending on whose studies you look at, five years after starting a weight loss program, 85-95% of people have regained all they’ve lost. Numbers are much better for surgical weight loss: there only 40% of people have regained the weight they lost, but people who qualify for weight loss surgery are uniformly obese and post-surgery less than 5% of them are no longer obese, they’ve just managed to maintain the weight they lost post-surgery.

So any plan that starts with “well just do this thing that has less than a 10% chance of working” is probably not going to have good results.

My genetics predispose me to being quite skinny, but my sustained and vigorous attempts to get from 8% subcutaneous fat down to 4%, over a period of 20 years of bike racing, were met with my body doing all sorts of interesting things none of which yielded a sustained sub-5% body fat percentage.

Nope. I am not overweight. I also don’t eat lactose, gluten or caffeine. Weight has nothing to do with it. Read the article – it’s neuromuscular.

Apart from the other excellent replies, this question was answered in the article pretty clearly i thought. The reason they are looking for a drug as an alternative to CPAP is that some patients do not comply with CPAP. Guess what, they don’t comply with weight loss either. An effective cure relies on meeting people where they’re at, that’s why magic pill solutions are so well-loved.

I lucked out I guess. Starting a CPAP had a dramatic effect on my sleep (and wakefulness) in a couple of days. I tolerate the mask well and I’ve used it every day for the last 15 years. I don’t think it affected my weight.

My original F&P gave out after 12(!) years and I got a new APAP. I ended up fighting it during the night so I turned off all the fancy features and run it as a basic CPAP. It took a while for the insurance to come through for the new machine so in the meantime I built my own out of a PWM module and a 12v fan in a cardboard box, and used the hoses I already had. It was noisy but “white” noisy so I didn’t mind it.