You’re walking through a gallery and stop to take in two seemingly unrelated pieces hanging side-by-side. One of them is a drawing of a bird, rendered with such precision its feathers could easily pop off the paper. The other is a sketch of what seems to be the same bird, however it’s nearly unrecognizable due to inconsistent line quality and parts that are entirely missing.

Order yours now

In staring at the photo-real drawing of the perfect bird, you marvel over the technical ability required to produce it. You also study the sloppy sketch just as long, picking out each one of its flaws, yet decide you like the image of the strange bird because the errors are interesting to you.

When you lean forward to read the title card posted on the wall between them, you’re shocked to learn that the two drastically different images were made by the same artist; not the person them self, but a machine they built to create both drawings in two different styles.

As an illustrator, I’m fascinated by drawing machines because their purpose is to emulate an act which has always been a highly personal form of self expression for me. Drawing machines and their creators are in a sense my peers.

Usually machines or robots that draw, regardless of type, are bound by the human influence of their creator. This causes most of us to see them as complex tools rather than collaborators… even though the human is more than likely just as dependent on the ability of the machine for the production of the work.

Really, the machine is a liaison between their own functional capacity to create images and the programming of their maker; a sort of co-dependent relation of ability between the two. Like with the perfect bird, the machine doesn’t have to develop a greater sense of spatial acuity to draw photorealistic images like its maker would have to. It relies on programming which leverages the strengths of a computer mind, acting as a shortcut to producing the sort of realism us humans struggle with.

The trade off is in the subtlety. Machines are rock-stars at executing precision, however the important quality of imperfection found in drawings made by humans is a lot harder to forge. Just like in painting programs, the simulated sable brush is only as believable as the software writer’s attention to how each fiber could potentially shift and splay in response to drag and pressure. Without these characteristics taken into account, every stroke would be a flat line, lacking what you’d probably define as feeling or expression; attributes that funnel into larger less easily definable ideas like creativity.

As the mind behind your drawing machine, how do you rectify something like feeling or gesture to produce works of expression like the strange bird?

The Machine as a Tool

Along with fellow robot builders of the world, I ventured to the San Mateo Maker Faire last year. Amidst the chaos I found myself lured into a booth which had a wall-hanging plotter pinned on the chain link fence in back. This particular type of robot tugged on memories from my distant past and got me talking to its creator, [Dan Royer].

I learned that [Dan] was in the business of designing robots and releasing them into the world as kits. By allowing the majority of his work to be open source, [Dan] hopes to start a collaboration with the world that will result in more capable iterations of his robots down the road. His means to an end being that these future renditions of his machines land themselves on the moon, either as capable tools or whatever they’ve evolved into by that point. Having lofty goals of my own, I respect this sort of ambition.

In order to design robots for a living, one must start out selling robots for a living. [Dan] leverages the sales of his self engineered creations to afford a life style of perpetual development. Because of this however, the element of production has a heavy influence on the way he designs his machines. Where 3D printing is a fantastic tool for rapid prototyping, it no longer becomes viable when you have to create a hundred of the same part.

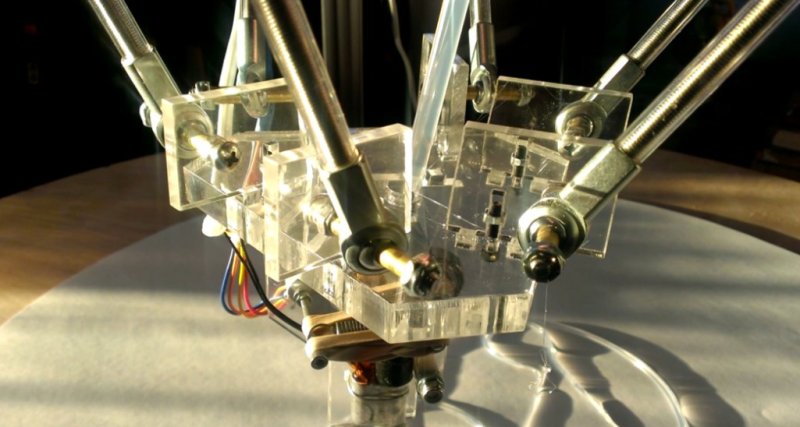

The solution for [Dan] in handling all of his own manufacturing was to invest in a laser cutter. With this tool he can quickly create complex and dense shapes by stacking layers of thinner material together… like a robot sandwich.

This method is implemented expertly with his 3-axis arm kit. Dozens of detailed cross sections pile together to create a robot that does more than just pick things up and place them somewhere. In spite of operating radially, it can produce accurate drawings too.

This method is implemented expertly with his 3-axis arm kit. Dozens of detailed cross sections pile together to create a robot that does more than just pick things up and place them somewhere. In spite of operating radially, it can produce accurate drawings too.

The arm rotates on a circular platform, so the use of X and Y coordinates would result in an image that looks like its been mashed into a funnel. To remedy this, [Dan] implemented inverse kinematics for the jointed robotic arm in order to create images that are proportionate.

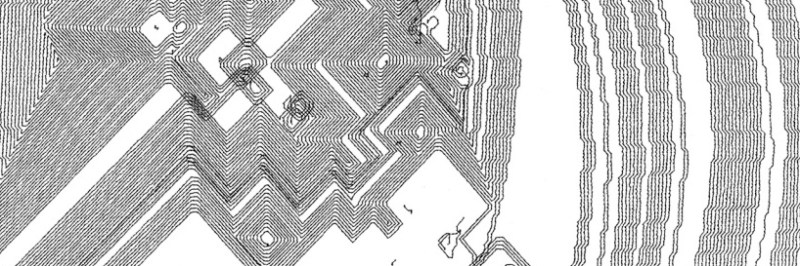

The arm was doodling away while I spoke with [Dan], but my attention was glued on the wall plotter a few feet away. This particular robot was his first success, dubbed the “Makelangelo”. Its creation was an indirect result of [Dan] teaching himself how to control stepper motors. In order to gauge accuracy, he would compare the axis of one motor against the other to see if they could consistently land at the correct spot. Naturally these sort of tests evolved into the production of drawings. If the motors could plot a series of coordinates over time and turn out the expected image rather than a rat’s nest of scribbles, then he knew he was making progress.

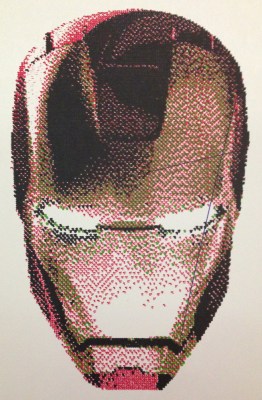

From the milestone of accuracy, [Dan] continued to develop other drawing styles for both the Makelangelo and the ARM. Like filters in Photoshop, these styles can be applied to any image and the plotter will act on code to re-skin the outcome.

From the milestone of accuracy, [Dan] continued to develop other drawing styles for both the Makelangelo and the ARM. Like filters in Photoshop, these styles can be applied to any image and the plotter will act on code to re-skin the outcome.

The goal for much of [Dan’s] work is to create a platform capable of producing works like the perfect bird, so that others can use this standard as a starting point. Like crafting an ideal paintbrush that the owner can then pluck bristles from to create an alternate stroke.

When designing the machine, what if perfection was never the point to begin with? What bountiful coolness could the pursuit of the unexpected yield?

The Machine as an Artist

At some point during my excursion in art school years ago, I diverted from illustration and threw myself into a robotics class. This being my first run-in with electronics ever, it felt a lot like taking high diving instructions without knowing how to swim.

To stay afloat, I channeled inspiration from the other seasoned tech veterans. For instance, the guy who sat across from me, [Harvey Moon], already had a reputation for designing and fabricating his own drawing machines. His work became the object of my fascination because I saw him as an inverse of myself; I being an artist that drew pictures of robots, he being an artist who made robots that drew pictures.

[Harvey’s] drawing machines were in a league all their own because they seemed to effortlessly pull off a sense of human-like feeling and style, which was a quality granted by the imperfections in the images they produced… Imperfections that appeared genuine, not canned or determined ahead of time.

By surrendering the outcome of the drawing over to the machine itself, [Harvey] gives the machine permission to have its own creativity. Yup. Let me tell you how.

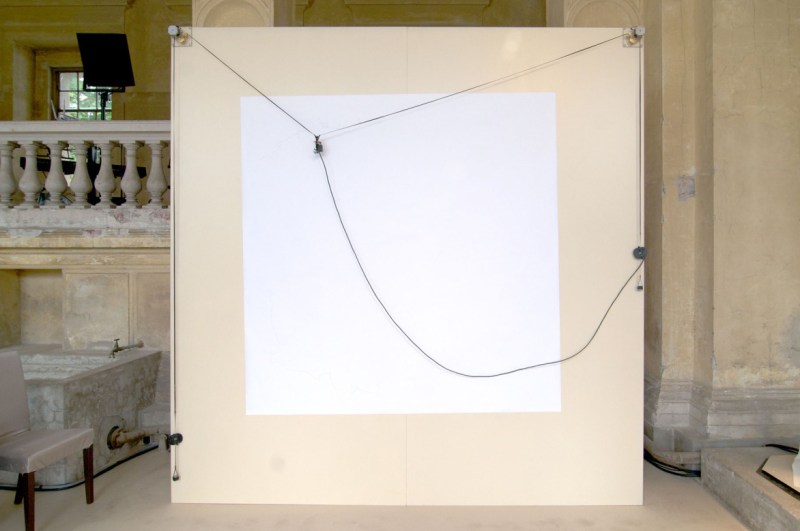

The Wall-Hanger

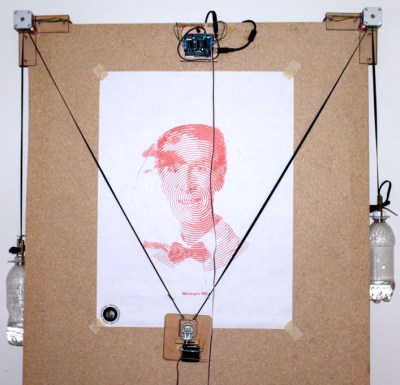

The project [Harvey] was known for by the time I landed myself in his presence was a wall-mounted robot. It was deceptively simple, but the elements were expertly developed to work exactly as he wanted them to.

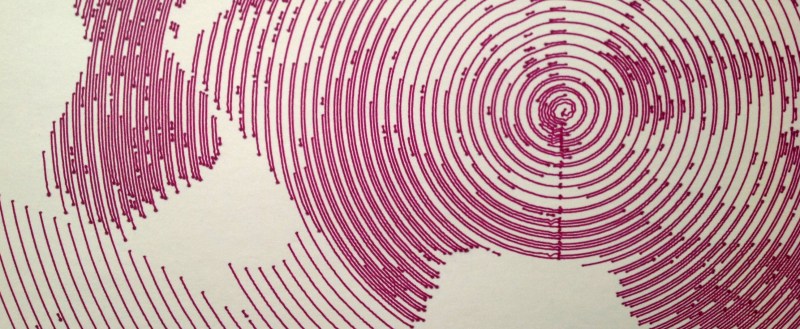

This little machine created lines inherent of the delicate tension between pen and paper like a seismograph. One continuous trail meandered in and around itself, becoming an image that lacked the precision indicative of machines while also remaining impossible to replicate by human hand.

Almost everyone is familiar with plotters of this flavor. The kind that tether a pen on a string between two stepper motors… acting in cooperation with gravity, like a spider weaving its web. They’re fairly common these days, but [Harvey] started building his first prototype at a time before they were as heavily documented on the internet as they are now.

Almost everyone is familiar with plotters of this flavor. The kind that tether a pen on a string between two stepper motors… acting in cooperation with gravity, like a spider weaving its web. They’re fairly common these days, but [Harvey] started building his first prototype at a time before they were as heavily documented on the internet as they are now.

Like the rest of us students in fine art, [Harvey’s] original passion was in a more traditional medium, photography. Without anyone else’s prior experience to use as a starting point, he had to begin from scratch, teaching himself the ins and outs of stepper motors by salvaging them from old printers.

This being his first project involving microcontrollers and programming, it would be years before he figured out how to coax a stepper into producing a drawing. Along the way, the dialogue of trial and error between [Harvey] and his work became integral to the meaning behind it.

He came to realize that he was more pleased when his machine failed than when it worked as he expected. If the output was always unknown, there was no way to grow bored of it. Due to this attraction to chance, it was never his intention to produce a machine that drew perfectly. He set his standard elsewhere.

He came to realize that he was more pleased when his machine failed than when it worked as he expected. If the output was always unknown, there was no way to grow bored of it. Due to this attraction to chance, it was never his intention to produce a machine that drew perfectly. He set his standard elsewhere.

But alas, you can’t really force a “happy accident”. The better [Harvey] became at his craft, the more work he had to put into engineering unpredictability. His way of pulling off this trick is through the use of clever algorithms.

Where most wall hanging plotters are given a starting image to copy, resulting in a more or less predetermined output, [Harvey’s] algorithms allow the machine to carve the path as it’s being walked.

To give an example of how this could work, the machine is similarly provided with a source image, however depending on what pixel it’s told to begin the drawing at, the result will be different each and every time. To pull this trick off, a program in Processing converts all of the pixels of the image into percentages of grey. From the chosen point of origin, the machine will continue to the darkest pixel in proximity, immediately whiting it out upon arrival so that it wont trace over it a second time.

Taiwan Wall-Hanger

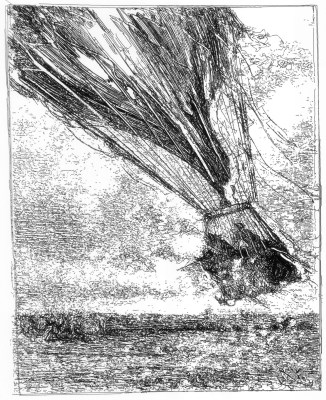

As his wall-hanger changed from iteration to iteration, [Harvey] continued to experiment with more ways to surrender his control over the outcome of the drawing. At a more recent exhibition at the National Taiwanese Museum of Fine Art, he decided to ditch the static image as a source and introduce the use of live video as a means to harvest unpredictable input.

For this particular installation, [Harvey] located live surveillance cameras in advance throughout Taiwan in areas with varying traffic densities. For three months, four of [Harvey’s] drawing machines slowly chugged away, faithfully attempting to replicate the ever-changing view seen by the camera. The resulting image was an original depiction of the passage of time created by the whim of chance.

To The Third Dimension!

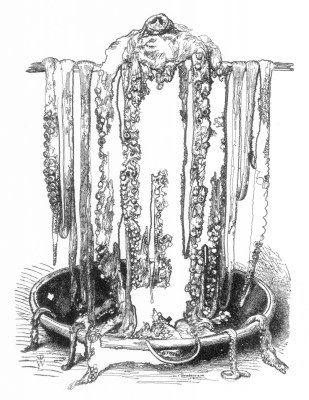

While thinking of new ways to abandon control over the content produced by his machines, [Harvey] considered ways of bringing dimensionality into the equation of his work. These thoughts resulted in building a delta robot as a new platform for experimentation.

Instead of focusing so much on input to derive chance output like he had with his wall plotter, the delta robot opened up new grounds to mess with different mediums as a way to create the unforeseeable.

Though delta robots are associated with industrial-grade precision and used as 3D printers for this very reason, [Harvey] wanted to break the common association.

Consistent with his desire to play with new and uncontrollable mediums, he built an extruder for the end effector that would spew out hot glue instead of filament. Really, there is nothing less controllable than gooey, stringing, completely irrepricable mounds of cooled molten plastic.

To end up with these intriguing piles of semitransparent goo, [Harvey] programmed a random shape generator in processing which would run in real time, producing G-code generatively as it went.

So, Tool or Artist?

As the mind behind your drawing machine, if producing a sense of feeling or gesture involves relinquishing as much of your own control as possible… at what point should your machine receive credit for what it creates over you?

I imagine the hypothetical situation where [Harvey] walks away form his installation in Taiwan never to return, and like a passage from some science fiction tale, the machine goes on to produce drawings for decades maintained by people in the community who no longer remember him.

With [Harvey] so far removed from the equation, who is producing the art at this point? Is it the person who restocks the paper? Or the people on the live camera feed providing the input? Or is it still [Harvey] because he’s to credit for the original idea?

Should Ownership Belong to the source?

Imagine this scenario. If you print a copy of a painting you made, you attribute credit for the art and the print to yourself, not the creator of the printing machine or the machine itself. You will go around and show people the copy and boast, “Hey look at the illustration I made!”. You assume ownership for the creativity, ability, and intent that was necessary for its creation, even though the ink on that sheet of paper wasn’t technically applied by your hand.

However, if during the process of printing that same image, the paper jams and smears ink all over the place in an interesting way, which you then hang on your wall because the accident was more interesting than the intended print… then what?

The smeared mess-up was based on input which you provided, on a machine that someone else invented… but the product was really a result of its own doing. Of course, there was no intelligent design behind what it made; none-the-less it was acting on data provided, its own functional capacity, and the right proportion of chance.

Lacking conscious decision, the misprint from your printer might not exhibit true creativity or imagination… yet as the process of producing art becomes continuously iterative and automated, taking on a life of its own, doesn’t the source become less important than the thing it evolves into?

Should Ownership Belong to the Person Who Provides the Code?

So you might be rolling your eyes and thinking to yourself, “Ownership will always go to the one who provided the code, because without it there would be no drawing, let alone anything iterative.”

You could also say, without the years of teaching provided by Michelangelo’s mentor, there would be no masterpiece on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, therefore credit should go to his mentor. Obviously, this argument doesn’t hold up because the synthesis of his mentor’s input has resulted in independently formed output, making it very easy for us to decide that Michelangelo’s artwork is his own, regardless of how large the influence.

The fact that someone originally left a robot with some artifact of code may matter less and less when we’re talking about continually more autonomous machines.

Should Ownership Belong to the Maker of the Machine?

If you believe that autonomous or not, credit for a machine’s “creations” should always go to whoever built it, then what about [Dan] who sells his as tools? His machines aren’t that much different mechanically from [Harvey’s]. So does [Dan] get the credit for each and every drawing made by a machine of his design, whether its in his lab or your living room?

That obviously doesn’t hold. If we’re talking tools, then the ownership belongs to the person using the tool to make the work. However, what if the tool is using itself?

Why do you think you should receive credit for the things you make?

A likely answer might be, because you were acting on your own ideas with your personal arsenal of abilities to produce the desired outcome. You might also say something is yours because it was a result of your creativity.

One definition for creativity is: a phenomenon whereby something new and in some way valuable is created. So again, couldn’t a machine satisfy all of these requirements for artistic ownership too? When approached, almost everyone I’ve asked seems to believe that the answer is obvious, and perhaps as of right now it is. Machines are made by us humans, so the work of a machine is an indirect result of our doing as well.

However, as we continue to include more complex devices in the production of our work, this question will continuously become more difficult to answer. When these tools are expected to make decisions that are further removed from the influence of a human mind, at what point does the machine deserve recognition for its creativity?

This article was specifically written for the Hackaday Omnibus vol #02. Order your copy of this limited edition print version of Hackaday.

Several points. That final definition of creativity is rather flawed and over-general. After all geological processes create new and valuable things, and yet most people would not call them creative.

As far as the long term scenario with the machine in Taiwan theoretically running for years. There is such a concept as collaborative art. One could use whatever moral and legal frameworks one has to examine it as such.

As relates to the printer accident scenario, there is also a concept of found art. In my opinion the finder gets some credit for recognizing the artistic merit of the result of processes that lack intention, but is still seen as a finder rather than a creator. Another example of such: who gets the credit for the natural beauty found in some cave systems (or natural beauty found anywhere).

One might also consider that people have been creating art from less uncontrolled processes for a long time. For example abstract artworks created by flinging paint at a canvas from a distance(more control), or discharge ferns in acrylic(less control).

I don’t suppose I have really contributed to answering any questions. I have merely pointed out some places this has been considered before.

Fun thing about computers:

If you can adequately define it, then the computer can be made to replicate it.

If you can’t adequately define it, how could you decide whether it can’t?

Applies to creativity too. Try defining the steps of the creative process sometime. :D

If this is art…. then these are masterpieces https://www.reddit.com/r/Shitty3DPrinting

Like with most things in the current state of tech, hardware is easy, software/firmware is possible, software/firmware doesn’t exist.

To see more plotter creations, there is a flickr pool:

https://www.flickr.com/groups/2164129@N25/pool/

If you do drawings in collaboration with machines, please contribute to the pool.

Duchamp much?

Art is whatever you decide it is.

once you stop making design decisions and let the machine take over, it becomes a creator. it only becomes an artist when what it produces can be defined as art, in a sense that it is visually interesting.

the closest it can get is by introducing entropy, but that just adds defect to bitmaps

At what point can something made be regarded as art to you?

essentially anything visually interesting can be considered art, but i’d go a step further and say anything that is, and was created with the intention of being visually interesting. surprisingly enough art can be broken down in to some guidelines. ( tension, dividing lines, triangular relations, patterns, flow, etc. )

Do you believe intent has anything to do with it?

One definition of “art” according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is “Works produced by human creative skill and imagination”. If you subscribe to this definition, the distinction is easy. In any case, the answer depends on how you define the word.

What ever you use to make art is maybe irrelevant… is it your intent and content in the making of art that is important?

Kind of related. Sort of related.

I like this talk by Devine Lu Linvega, talking about how he speculates that today’s artists will soon become curators instead.

https://vimeo.com/138850582

This is interesting, thank you.

Robot art competition: http://robotart.org/

Here you can get real pendrawing based on an image you provide, for the most part drawn by a machine. http://www.epenko.com/

Perhaps is art that what is made specifically to be beautiful or to surprise you or yo make you think about something. Art should be able to evoke emotion and ideally remains interesting for a longer period. For other pen drawings than in this article made by a machine, check out: http://www.epenko.com

Art becomes art at the moment of it being perceived, recognised as such. This recognition, and accompanying “Hey, you need to see this!” message to someone other is what makes art. Art is sharing of a Zen moment. If it doesn’t move you, if you are not getting it, then it is just rubbish (for you). So, if machine “gets it” and wants to share that with us, then machine is creative.

You’re suggesting creativity is more of a dialogue. If a machine can’t participate in the dialogue, do you think creativity is strictly a human attribute then?

I am suggesting art becomes art when someone recognizes it as such. Creativity is perhaps misunderstood or even does not exist as some intrinsic property of a subject. Even humans can’t get creative on command, there is some underlying chaotic psychological process which probabilistically generates moments of inspiration (if they are recognised as such by creator’s own mind). So in essence, the creation is blind, but ability to keep both discipline and free flow of thoughts, together with sensitivity of inner recogniser is what makes distinction between ordinary human mind and “creative” one. Now, back to suggested machine-human divide, I think that humans are machines too, but not stripped down ones like we make. Our main characteristics relevant to this discussion are tendency (selective internal reward for some outcomes of our behaviour), curiosity, attraction to novelty – when our brains experience something new (but not associated with detriment), not previously completely classified, we feel reward – that’s that “Ah ha!” moment. Now, if would make machine which constantly analyses its inputs and builds its internal tree of notions, and if it would increment positive “satisfaction” property variable whenever it has novel experience, I would deem such machine capable of understanding art. From that point on, it would be capable of creating art too.

Years ago I worked for a douche-bag manager who tried to slap his name on every patent from his department. But years earlier, the courts had ruled that you can’t “induce” people into being creative, and hence the manager deserved no patent authorship credit. You might provide a conducive environment, or machines, or supplies or materials, but that’s a different story.

And so it goes with art. Art belongs to the artist. Not the software, or the guy that wrote the software. Not the machine, or the guy that built it. It’s a slippery slope. Do you want to be liable for the nasty letter someone wrote using your pen? Or the graffiti from your spay can?

Here’s a good example : http://hackaday.com/2015/01/04/darknet-shopper/

It’s an art installation where a program is created to randomly browse the black market and buy things, then have them shipped to the gallery where they were put on display.

The artists had no control over what the bot purchased. The installation roused questions, whether or not the artist should or could be held responsible for certain illegal items bought by the machine.

“Because Art: Can Machines be Creative?” – Huh? Humans are machines. Humans are creative. Ergo: Machines can be creative.

+1

I gave a presentation a month ago that was partly about this subject. It’s mostly an overview of progress in this area, but I also came up with a way to divide computer creativity into “meaningful” and “meaningless”, which might be useful for others interested in this.

Briefing note, slides with speaker notes, and Q&A: https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B0IsgXgI9Rn-WjJyMU11OTBuSlE&usp=sharing (Followup presentation isn’t worth including.)

Thank you for sharing this!