More and more, the power grid is distributed. Houses have solar panels on their roofs, and where possible, that excess power is sold back to the grid. The current trend is towards smart meters that record consumption for an entire household and relay it back to the power plant every day or so. The future is decentralized, through, and a meter that is smart once a day simply won’t do. A team on Hackaday.io has put together the ultimate in decentralized energy modernization. It’s the InternetS of Energy, and it removes the need for power companies completely.

The team has identified a few key features of the current power grid that don’t make sense in the age of the Internet. The power company doesn’t have extremely granular data, and sending power over long distances is either inefficient or expensive. The solution for this is to have distributed power plants, all connected together into a truly intelligent power grid.

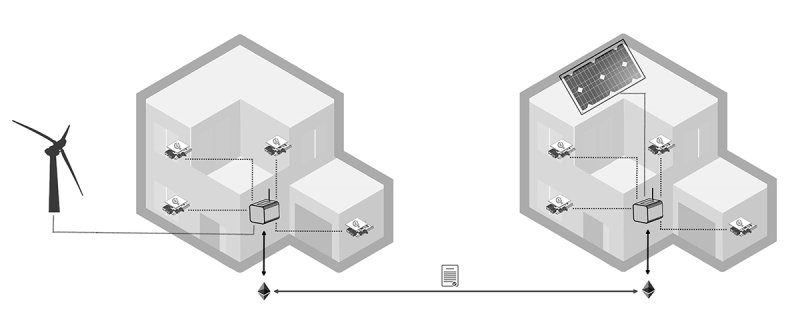

This InternetS of Energy uses open-source energy monitoring systems running the Ethereum client to push power-usage data onto the blockchain. This makes the grid secure and pseudonymous, and if the banking industry is any indication, something like this is the future of economic transactions.

While it may not be the best solution for mature power grids, it is an extremely interesting avenue of research for developing nations. Wherever local resources allow it, electricity can be generated and sent to where it’s needed. It’s exactly what the power grid would be if it were re-designed today from scratch, and an excellent candidate for the 2016 Hackaday Prize.

In California, the state government is passing a law to charge solar producers money to subsidize the money being lost by the big energy producers.

My point being, this sounds great! Good luck with that!

Nice Idea, but “removes the need for power companies completely”

Meybe they have an idea who shall build and maintain those infrastructures like High voltage Cable and Wire lines, Transformer stations etc.

Not that these tasks can be managed decentralized very well. Some people have to keep all the stuff between your and every others house maintained and upgraded if needed… …those people want a paycheck…

Maybe the same people who build and maintain roads? Local councils for suburbs, city councils for cities and towns and state councils for state, intercity and interstate. The last one is the one which is the least efficient and so could maybe be axed, especially given it is likely the most complex to govern. Also council is interchangeable with private interest/company or a consortium of local residents, governments are useful but definitely dont need to be a first option where possible. New Zealand has a number of local resident groups investing in construction and maintenance of power infrastructure, including generation, transmission and economics.

people who maintain roads, so, nobody.

if everyone has solar panels and we don’t need power plants then we don’t need a grid at all right?

Congratulations, Josh! You just recommended replacing power companies with power companies! In the area where I live, there are city-owned electric utilities, corporate electric utilities, and co-op electric utilities: each and every one of them is an electric company, because each and every one of them exists for the sake of reliable distribution of electric power.

Frankly, the project looks to be full of nonsense and lack of awareness. Electric producers are regulated, yes: but not as much as electric distributors (power companies), who are directly under the thumb of the local corporation commission. Long-distance transmission is inefficient? Just change the voltage or transmission system and that’ll fix itself.

If you don’t know much about the subject then their idea hits all of the right-and-vague buzz-words, but lets look at the general categories of problems that they’ve identified:

1) Lack of data – already being solved in the first-world with the smart grid. The solution for the third-world is… a cheaper smart grid. So perhaps they should reprase their hyperbole?

2) Energy losses – as I said, change voltage or transmission systems.

3) Lack of use of local resources – three problems here,

I) Local resources are rarely of sufficient quality or consistency – solar and wind sound nice, but both are “burst” technologies, and what you really want are “endurance” technologies. Cheap bulk energy storage (my choice is hydraulic energy storage between a pond and coated salt dome: neither cheap nor casually constructable, but should work well when it’s there).

II) Local resources are rarely developed – you’re better off figuring out a cheaper and maintenance-free generator than worrying about information.

III) Local resources are rarely of sufficient controlability for what they describe – peer-to-peer energy transactions sound great if you don’t worry about implementation, but when you do you see that only hydro and fuel based systems will work, because those are the only ones that allow production to adapt to the demand-side instead of the production-side: you can’t just “turn on” the sun or wind.

4) Consumer interaction – the only interaction that consumers WANT is paying the bill and flipping the switch.

5) Complexity – that’s one of the reasons you pay the power company.

6) Trust – if you can’t trust them, then reform the regulatory system.

7) Consumer involvement in energy governance – California attempted to reform it’s energy sector in the 90s through democratic process. The lesson learned is that technical fields are best regulated by technocrats instead of democrats. The energy sector warned the legislators that what they were being told was nonsense, the legislature threatened to charge them with perjury, went through with it, and discovered after-the-fact that the lobbyists that had been giving them all of that “great” advice were just looking for cheap infrastructure that could be moved out-of-state. One of the reasons that California’s been pushing solar for so long is to help clean up the mess caused by the combination of this, and the impossibility of building new generation plants in California (the environmentalists shut them down after construction, but before activation, resulting in all of the cost with none of the benefit).

Finally, DAISEE has a big problem: without a distribution grid what they’re discussing can’t happen, and a grid requires reliable maintenance. That, in turn, calls for an electric company. And that, in turn, calls into question why you’re trying to use decentralized technologies for an inherently centralized system.

Some of the things required for this project are good ideas: cheaper smart-grid technology is an enabler for third-world alternate-energy, since it can allow local power to be harnessed at all. But let’s be honest here: unless we psychologically turn into ants, there’s no way to implement grid-free power distribution without so many leechers that the system collapses.

Yeah, but the grid is the one connecting us to the sun. God, what it would be like without the wires everywhere. That what battery power is really about, we’re not talking portable stuff. Additional powerplants of many fuels, for demands, and at locations as needed. A number of manufacturing plants co-generate power on site to meet peeking prices already.

Duke or whoever maintains all of those corroding wires on dead trees and rusting steel that run everywhere is the reason for such backlash to co-generation because they see the end run with everyone getting in on the act.

A day when we are fiber optic and wire free, distributed power and EMP proof. Or at least able to shrug off sun farts!

These delivery networks, in all of their manifestations, have two roles: moving the stuff from production to consumption; and guaranteeing a reliable supply (and demand) by connecting multiple numbers of each. The second factor, although often understated, is just as important as the first. Reliable access to markets encourages production; choice of suppliers keeps prices under control, encouraging use. At least that’s the Intro to Economics 101 theory, and broadly viewed over the long historical axis, a correct one.

The energy networks have one other important property that cannot be ignored. They are there. Vast sums of money, time and material have been expended over the better part of the last century building these things and polishing the procedures to make them run. The only way we were able to afford these huge systems in the first place is that they grew slowly and the products that they moved were so inexpensive to produce that the consumer could absorb the cost of construction almost without noticing.

The point? Many of the proposals out there, some which are being seriously considered, involve retasking one or more of these systems, and in many instances this critical issue is breezed over in discussion. This is a mistake. These systems are huge and complex, with a bewildering number of control nodes and operate under protocols that been less designed then they have accumulated. They have not been built for two-way traffic, and even in cases where bi-directional flow is physically possible it is often achieved only by overriding system fail-safes, and potentially compromising product integrity. Refitting to allow for this, while certainly doable from the engineering standpoint, would be horrendously expensive, and in some cases would require that large chunks of the network go off-line or isolate for extended periods of time and in most cases this factor alone makes conversion unfeasible.

The second overarching technical concern is reliability. We use energy in such a way that an unreliable source is often worse than no source at all. Many of our day-to-day behaviors are predicated on subliminally knowing that the juice will be right there, right now, when we throw the switch or turn the key. If you’re a backwoods camper, or stay in a country place off the grid, you make adjustments, but we cannot run our lives not knowing from moment to moment if power will be there. Yes, that’s the case in some third world urban pestholes, but those are not the conditions we are striving for.

Thing is each node whether a gigawatt natural gas power station or a single solar photovoltaic panel needs to be controlled and the necessary number of combined control tasks multiply as devices multiply. requirement of implementing Flexible AC Transmission Systems (FACTS) technology increases the number of control parameters. Accurate information on the state of the network and coordination between local control centres and the generators is essential. However an inherent risk of interconnected networks is a domino effect – that is a system failure in one part of the network can quickly spread. Therefore the active network needs appropriate design standards, fast acting protection mechanisms and also automatic reconfiguration equipment to address potentially higher fault levels. On top of which most of the proposed systems require intelligent loads as well, adding to network complexity and cost. As I stated above these changes are not cheap or easy.

The only way to assure reliability is obviously, to have reliable reserves on hand at all times. Bluntly, safe, affordable, local high density, storage technologies are not yet ready for large-scale deployment. The practical systems available now are too costly and too dangerous both to the user and the environment to be in general use. Adding to the complexity of this sort of system is that it would require storage technologies that can store significant amounts of power and reliably discharge it over and over again. Most of the candidates suffer from poor power density, as in standard batteries and flywheels; high complexity, in the case of molten salt and regenerative fuel cells, or are limited by location such as subterranean compressed air and hydraulic storage.

Very good points. I would like to tell my view as a designer of grid level technology.

Distributed generation is great but a few of the problems you run into are

Cost: Economies of scale allow your power company or GNT to generate power through solar, wind, natural gas, or whatever else for vastly cheaper due to the scale of the operation. Small scale solar or wind is significantly higher in cost and has other issues and without net metering most household solar would be gone and is only cost effective because of this and subsidies (right now).

Control/ Reliability: With distributed systems that are not under the control of your power company can lead to failures of equipment and outages. A good example is grid tie solar in Germany and California. If a blink on the system happens the grid ties start to island and if they are a significant source of energy now you loose your supply of energy till your power company comes back up so now the system has to be designed for the full load and not even supply it. Other issues involve inductive versus capacitive loads of the generation, oscillations of line hardware like capacitor banks, not being able to rely on generation outside of your control, designing for peak usage, etc.

Automated Meter Reading:

Many meter reading systems are slow. Many power companies have once a day but also many have less than 10 minute interval data through there AMR system.

Efficiency of Systems:

Electrical grids are actually pretty efficient and elegantly simple in many ways. Many of my customers (power companies) have incredibly efficient, fault tolerant, well tuned distribution systems but a vast majority are just not to that point. These past couple of years the incentive to have more distributed control and monitoring has given these companies data that they could only dream of before allowing them to make efficiency improvements that saves them money and ultimately save you money.

While the situation in the First World may not be as grim as when I first penned the passage above fifteen years ago, the idea, floated in the lead post, that this might work in the Third World is risible. Anyone that has seen the state of power distribution, especially on the last mile will swiftly realize that there is simply no possibility of implementing any sort of sophisticated distributed system in these places.

But the broader point remains: Even in the West it is not clear that the grid is robust enough to tolerate the sort of peer-to-peer energy internet that the DAISEE project is about nor that the cost of upgrading the plant (never mind the control software) will ever pay off. This sort of system may have some utility in small, off-grid communities but it will never be cost effective on the main grid itself.

I agree with the article. The decentralization requires no fancy new technology as long as the percentage capacity is limited. With locally generated power the grid can take a break on sunny days. All that is needed is to get the regulations removed that have been installed by utilities solely to protect their dominance.