Film photography began with a mercury-silver amalgam, and ended with strips of nitrocellulose, silver iodide, and dyes. Along the way, there were some very odd chemistries going on in the world of photography, from ferric and silver salts to the prussian blue found in Cyanotypes and blueprints.

Metal salts are fun, and for his Hackaday Prize entry, [David Brown] is building a printer for these alternative photographic processes. It’s not a dark room — it’s a laser printer designed to reproduce images with weird, strange chemistries.

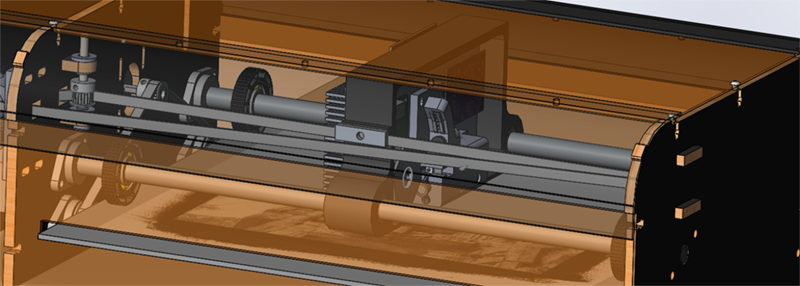

Cyanotypes are made by applying potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate to some sort of medium, usually paper or cloth. This is then exposed via UV light (i.e. the sun), and whatever isn’t exposed is washed off. Instead of the sun, [David] is using a common UV laser diode to expose his photographs. he already has the mechanics of this printer designed, and he should be able to reach his goal of 750 dpi resolution and 8-bit monochrome.

Digital photography will never go away, but there will always be a few people experimenting with light sensitive chemicals. We haven’t seen many people experiment with these strange alternative photographic processes, and anything that gets these really cool prints out into the world is great news for us.

Nasty chemicals!

Perhaps a IR laser charring natural materials like wood could be used.

There’s nothing nasty about cyanotype chemistry. Both ingredients are nontoxic. Charring wood will certainly evolve much nastier stuff.

It’s not particularly toxic unless it burns or reacts with an acid.

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Potassium_ferricyanide#section=Safety-and-Hazards

…I will say that printing directly onto wood optically sounds awesome!

I know I’ve seen it somewhere on the web, will look for it later.

wouldn’t that just be laser engraving?

Well, I got ahead of myself.

I was thinking about wood pyrography using sunlight but couldn’t remember what it was called.

Prussian blue can be used as an antidote for thallium poisoning…

You can eat quite a lot of this stuff, it’s no worse then TiO2 which in nearly everything that’s bright white and edible, only difference is that it’s blue ;-)

+1

It is a common misconception that photographic film is still nitrocellulose (as in: ‘and it ended with’). It was, way way back, but unfortunately not still in my childhood. And I’m turning 50 next year.

Probably polyester (mylar)

No, only certain films. Movie prints, archival film, and some traffic and surveillance films. Most still and movie camera films are Acetate base. They’re notable for degrading into Acetic acid from thermal reactions over decades. This is why all film is chilled, and polyester is used for archival products.

I can still remember the smell of the Diazo machine we had in the technical drawing room at school when I was a kid back in the Sixties. Even then most of us guessed that this process would eventually be replaced by xerography.

Ha. They took their time. I was still making diazo prints at work in the eighties. It was ’83 before I saw my first large-format toner-based copier.

There was still a place where you could get this type of print done in 2000 near me too, (maybe you still can) but why they had a market has never been clear to me. The same place offered a few different large-format printing options, so the process was still there because of demand.

From what I remember in the 80s…. for SOHO it had some advantages as a document copier into the 80s but as xerox copies and machines got ever cheaper and smaller into the 90s it lost them. A letter/A4 format machine was quite compact, it was basically a light box with a couple of rollers, about the size of a flatbed scanner. It was cheap, costing as much as a portable TV, whereas xerox machines started at the price of a small car. At the beginning of the 80s I think the price per impression of xerox was higher, but that came down rapidly, while the paper for the Diazo crept up in price until it was double or triple the price. Then by that time there were copiers in libraries and corner stores you could feed with dimes. Some people held onto them for convenience, i.e. working at 10pm and nothing open.. but as we got into 90s, paper became special order and $$$, and most people dumped them for DTP. Not forgetting also that the “any kind of copy for backup” market was also encroached by fax machines.

I work for the largest repro company in the country. We still sell Diazit supplies to a handful of customers. When you need to make a copy of a technical drawing that’s 50+ years old, it’s the only existing copy, and you need to keep the scale 100% accurate, an old school blueline is still the best option. None of our digital LF equipment guarantees better than 5% dimensional accuracy for a copy/scan.

then you are using the wrong digital equipment, i have done plenty of technical photography where dimensional accuracy was required.

true, chemical copying might be easier for something like simply replicating blueprints, but try digitizing maps or seacharts, especially when different or inaccurate projections were used in the first place and many of the physical maps are anything but flat at this point.

Film photography has not “ended”.

“…ended with strips of nitrocellulose, silver iodide, and dyes.”

it tru tho, film iz ded

Nitro would make it dead in the 1930’s. Movie film from the 1940’s smells like vinegar when you open a film can because the acetate film base is turning into acetic acid.

OK, not completely. Similar to music playback. A diminishing community of people are even still using vinyl records. Both similar outdated technologies mostly replaced with much better and more comfortable digital technologies.

Yea, it will just become a medium for art, like painting.

“Digital photography will never go away”. This is still digital printing, but with old-school chemicals instead of toner or ink.

Nothing is being printed here since no material is being transferred.

What about thermal printers?

True, but it’s still digital. You don’t have n-bits of analog depth!

the universe probably doesnt either.