We sometimes look back fondly on the old days where you could–it seems–pretty easily invent or discover something new. It probably didn’t seem so easy then, but there was a time when working out how to make a voltage divider or a capacitor was a big deal. Today–with a few notable exceptions–big discoveries require big science and big equipment and, of course, big budgets. This probably isn’t unique to our field, either. After all, [Clyde Tombaugh] discovered Pluto with a 13-inch telescope. But that was in 1930. Today, it would be fairly hard to find something new with a telescope of that size.

However, there are ways you can contribute to large-scale research. It is old news that projects let you share your computers with SETI and protein folding experiments. But that isn’t as satisfying as doing something personally. That’s where Zooniverse comes in. They host a variety of scientific projects that collect lots of data and they need the best computers in the world to crunch the data. In case you haven’t noticed, the best computers in the world are still human brains (at least, for the moment).

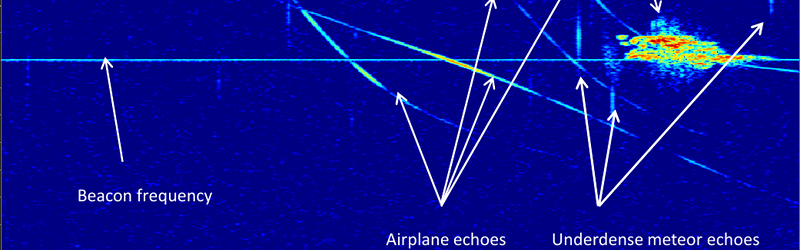

Their latest project is Radio Meteor Zoo. The data source for this project is BRAMS (Belgian Radio Meteor Stations). The network produces a huge amount of readings every day showing meteor echoes. Detecting shapes and trends in the data is a difficult task for computers, especially during peak activity such as during meteor showers. However, it is easy enough for humans.

There are many other Zooniverse projects if that one doesn’t fit your fancy. You can search for comets and supernova, study animal behavior, help transcribe documents from Shakespeare’s contemporaries, or study weather patterns from old ship’s logs. You won’t get paid (or charged, either) but you’ll be helping science and maybe learn something, too. The typical project gives you some form of training and relies on many people evaluating the same data to ensure the quality of the results is good.

You can find a video about an older Zooniverse project, below. In that one, you classify shapes of distant galaxies. Don’t get us wrong, though. There’s still independent citizen scientists out there. We have even covered a few of the more notable specimens. These are great projects to spur the interest of a budding young scientist, or rekindle the scientific spirit in us old timers. Would probably make a fair classroom project, too.

And here I thought Pluto was discovered by mathematical inference and verified by direct observation. Color me confused.

That’s Neptune. Oddities in the orbit of Uranus led to predictions of another planet out there. Soon afterward, Neptune was discovered right where the predictions said it would be.

The fun one was when they calculated the location of the planet Vulcan.

BioMed research has been doing this for a while now. Games like Eterna FoldIt, & Phylo use people to match patterns and help create new research drugs, or map D/R-NA for a variety of organisms and ailments.

Pluto was discovered by comparing photos made with the 13inch of different times of the same spot of sky where it was expected to be.

Many new comets are found by amateurs in their backyard with 12inch telescopes, sometimes by eye.