Imagine it’s 1943, and you have to transport 1,000 P-47 fighter planes from your factory in the United States to the front lines in Europe, roughly 5,000 miles over the open ocean. Flying them isn’t an option, the P-47 has a maximum range of only 1,800 miles, and the technology for air-to-air refueling of fighter planes is still a few years off. The Essex class aircraft carriers in use at this time could carry P-47s in a pinch, but the plane isn’t designed for carrier use and realistically you wouldn’t be able to fit many on anyway. So what does that leave?

It turns out, the easiest way is to simply ship them as freight. But you can’t exactly wrap a fighter plane up in brown paper and stick a stamp on it; the planes would need to be specially prepared and packed for their journey across the Atlantic. To get the P-47 inside of a reasonably shaped shipping crate, the wings, propeller, and tail had to come off and be put into a separate crate. But as any reader of Hackaday knows, getting something apart is rarely the problem, it’s getting the thing back together that’s usually the tricky part.

So begins the 1943 film “Uncrating and Assembly of the P-47 Thunderbolt Airplane“ which has been digitally restored and uploaded to YouTube by [Zeno’s Warbirds]. In this fascinating 40 minute video produced by the “Army Air Forces School of Applied Tactics”, the viewer is shown how the two crates containing the P-47 are to be unpacked and assembled into a ready-to-fly airplane with nothing more than manpower and standard mechanic’s tools. No cranes, no welders, not even a hanger: just a well-designed aircraft and wartime ingenuity.

Frustration-Free Packaging

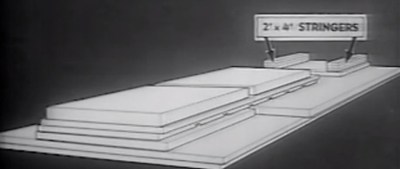

The key to the process of assembling the P-47 is in the crates themselves. They are not simply wooden boxes, but they make up an integral part of the assembly process. The film instructs that crates are to be taken apart in such a way that they can be turned into a makeshift cradle to hold the principle parts of the aircraft as they are bolted together. An incredible amount of planning went into the procedure for assembling this work platform; in several points of the film the viewer is instructed to cut large notches from the wood that don’t seem to have any purpose, only to find that twenty steps later a piece of the ever-growing aircraft will have to pass through it.

Further, structural parts of the crates are to be reused as levers during some of the heavier lifting maneuvers. For example, timbers which originally lined the sides of the main shipping crate are to be removed, cut in half, and nailed together. They will later be used as a sling when it comes time to lift the massive wings so they can be bolted to the fuselage.

Keeping it Simple

Once the work platform is completed, the film then goes on to describe the assembly of the aircraft itself. As promised in the beginning of the video, no specialized tools are required. In fact, no powered tools are required, as everything can be done with nothing more than human muscle.

This is especially evident during certain parts of the film, such as when the viewer is instructed to only use two fingers when pulling on an eight inch wrench so the tension can be estimated. Other times, the film advises manually counting how many threads are visible on the other side of a nut to determine if they’ve been torqued down enough.

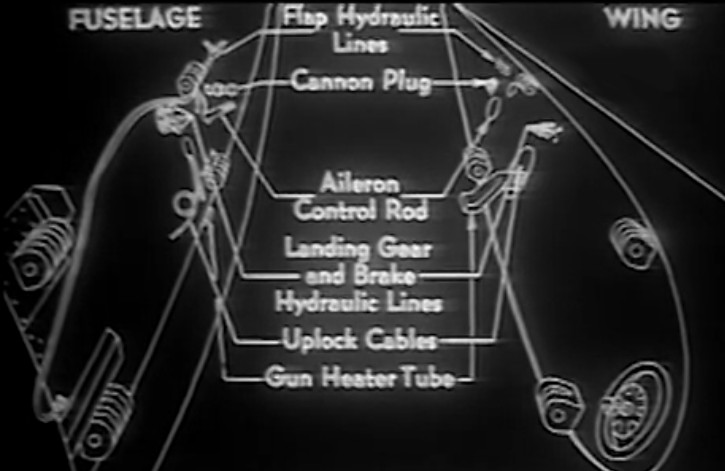

When things start to get a little more technical, such as when it’s time to connect all the wires and pipes inside the wings, the film relies on classic 1940’s illustrations to simplify the procedure as much as possible. Even if you had no idea what each component actually did, you’d be able to follow along and get it together correctly.

Part of the reasoning behind using the simplest tools and methods was necessity: if you were trying to build this plane on a battlefield when the enemy may only be a few hours away, you want to keep things as simple as possible. For example, rather than assuming there would be jacks or a crane available to lift the assembled plane out of its shipping cradle, the engineers designed the landing gear so they could be pressurized with nothing more exotic than a bicycle pump: thereby allowing the P-47 to lift itself out of the cradle and simply roll away.

Designed by Necessity

It’s this aspect of the aircraft’s design, enabling assembly by potentially unskilled workers with nothing but the bare essentials, that is perhaps the most impressive take away from this film. It isn’t as if they took a standard aircraft, ripped it apart, and told some GIs to put it back into one piece. The P-47 was clearly designed (at least in part) to facilitate this kind of ad-hoc construction and maintenance; which is no small feat for such a complex piece of machinery.

At a few points in the film, supplemental printed documentation is referenced so admittedly we don’t have the complete picture as to what it really took to get a P-47 out of its crate and into the air. It’s possible the printed documentation was extremely complex and involved tasks that were beyond the capability of your average soldier in 1943. It could even be that this film is more of a PR stunt than it is working documentation. We may never know.

While a worldwide conflict on the scale of the First and Second World Wars is something no sane person wants to see fall upon our civilization again, one does have to marvel at the way technology and engineering rose to the challenge it presented. During those years, the impossible became possible, and the unimaginable turned into the routine. There’s a certain bittersweet irony in the knowledge that, with any luck, humanity will never again be burdened with this all-encompassing drive to push the limits of man and machine.

And the tradition continues to this day.

When gliders run out of “up” and make an impromptu visit to a farmer, retrieval involves plucking off the wings and stabiliser and transporting them in a long trailer.

If hangar space isn’t available, gliders are often stored in their trailer and rigged at the start of the day. Top tip: never interrupt someone during rigging; they might miss an important step.

Missing an important step is okay. They won’t do it again.

” But as any reader of Hackaday knows, getting something apart is rarely the problem, it’s getting the thing back together that’s usually the tricky part.”

That why we don’t come with a “some assembly required”. :-d

“The key to the process of assembling the P-47 is in the crates themselves. They are not simply wooden boxes, but they make up an integral part of the assembly process. ”

Packaging is a field unto itself, from eggs, to aircraft. Add in “looks nice” for a challenge.

>in several points of the film the viewer is instructed to cut large notches from the wood that don’t seem to have any purpose,

>only to find that twenty steps later a piece of the ever-growing aircraft will have to pass through it.

Heathkit manuals were like this too. Skip an “unnecessary” step, or install a part before it’s called out and you WILL be doing part of the job over!

And tat works fine for everyone who just follows along. For those who jump around, at some later point they realize why the step was earlier, because something arises because they did things out of sequence.

If you know nothing, you aren’t wondering if there’s a reason for the sequence, trying to decide if the manual is badly written (non-Heathkit manuals may not be so specific, so the sequence might be arbitrary), or there is a proper sequence.

Heathkit also did things like put a small meter on the back of some of their color TVs to aid construction. Not much added to the cost of the set, but helpful to the builder. Though, it served no purpose when the tv set was running properly.

Heathkit also sold a radio scanner which included a few extra parts so you could build a 10.7MHz oscillator to beat with the radio’s local oscillator to get a signal on the signal frequency to align the front end tuned circuits. I’m sure there were other examples of that bootstrapping.

Michael

As a manufacturing engineer, that is one problem I often run across. I had an assembler claim the procedure was wrong (it was for a product several year old), but in really they just missed a step.

That’s alright. I was once instructed to place the instructions for disassembling a computer case inside the computer case before assembling it.

I got a call one time from another division of the company I was at saying that they couldn’t deploy our software and that they had followed the instruction very carefully. So, I opened up a new computer and followed the instructions exactly. I found that if you followed the instructions, there was no way it would ever work. Which meant that in the two years those instructions had existed all of our customers were smart enough to ignore the one (extremely stupid) wrong step in the instructions. Having customers that smart was a new one for me. Of course, none of them reported the problem…….

Damn, that’s gotta be one of the most interesting videos I’ve seen this year! I never know what I’m going to learn in the next Retrotechtacular post. Keep ’em coming!

Short glider rigging: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f2G9O1yu-Jw

Longer, but shows more detail from 1:35 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mV07_Na0d1w

Enter the age of tl;dr where any step may be “unnecessary”.

TL;DR: put plane together

There, done!

Now fly it.

A further evolution of this would be to ship containers of components that had to be made with conventional machining, casting, molding, and layup – and a 3D printer with a load of raw material for the rest.

And a time machine to finish the process before you are overwhelmed by the enemy :-)

Damnit, great film and makes me wish I had rental and fuel money now, even so I have no time to fly til January, I have to reserve a plane for then.

I so wish I had a crack at all of those beautiful war surplus planes back then, how fun to do an uncrate like this with folks from the neighborhood.

Now US warbirds are sold or scrapped, but they burn so much fuel it isn’t for kids with shallow pockets like me anyways.

It’s not just the fuel that would eat you alive, the maintenance is also a $$$ hog.

Tis why I rent for now, actually more expensive but I let the company do the work and logging.

“There’s a certain bittersweet irony in the knowledge that, with any luck, humanity will never again be burdened with this all-encompassing drive to push the limits of man and machine.”

If we survive every hurdle to when the only remaining one is the heat death of the universe then the drive will be to collect, store and conserve energy on an nigh incomprehensible scale.

I for one hope we continue to be burdened with an all-encompassing drive to push the limits of man and machine, not from conflict and war, but more for the sake of advancing and improving ourselves and our surroundings.

Oh good, that’s something to look forward to then.

At the very end, it says it’s “A Jam Handy Picture”. Google jam handy for another interesting story.

Thanks to the Zenos Warbirds People for this restoration.

^ What he said – Jam Handy films are brilliant.

I’m now trying to remember if any of them got the MST3K treatment?

Counting threads that are sticking out is probably just as good as a cheap torque wrench…in fact, provided that the fasteners are all made to the same spec, measuring rotation of the nut is actually more precise at reaching the desired load then torque wrenches, which are easily +-30% due to variables in all kinds of friction.

Actually counting threads is more of a ” Did you use the correct bolt ” issue. Aircraft bolts are supposed to be designed for shear not pull loads. Torque is just to keep the nut from loosening.

Many of these planes were assembled in Sydenham, Ireland (outside Belfast). To see how the natives assembled them: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXpzEo0cyVI

Note the propeller being put on wrong :-)

There’s more than a few steps wrong in this assembly, but they were clearly doing more of the assembly in parallel. I noticed the propeller was adjusted before it was hoisted into place, rather than in position, so at least pitch control probably worked.

Nope…in the field that would be pretty much the correct way to build any aircraft…helicopter, airplane, etc…landing gear or a way to move the vehicle first, uncrate and prep if it isn’t down prior, main wings, secondary wings(tail fines or tail rotor), all controls and final assembly if not done during prior assemblies, fine tuning, testing, adjusting if needed…landing gear would always be first because you may need to move the vehicle before continuing any assembly, and finishing the engine(on an airplane at least)has to be down after main wings and landing gear, etc., because if engine is accidentally started, the torque could overpower the fuselage and flip it on it’s side or back…

I enjoyed both watching the film and reading through the comments here. It did seem like the nifty IKEA idea of easy assemble planes, is this something that still occurs now though? Also, interesting to check out JAM Handy films as earlier shared by other user in the comments section. Thank you for sharing this though! I wouldn’t have been able to see that video in youtube if it weren’t shared here.