When we look back to the 1970s it is often in a light of somehow a time before technology, a time when analogue was still king, motor vehicles had carburettors, and telephones still had rotary dials.

In fact the decade had a keen sense of being on the threshold of an exciting future, one of supersonic air travel, and holidays in space. Some of the ideas that were mainstream in those heady days didn’t make it as far as the 1980s, but wouldn’t look out of place in 2018.

The unlikely setting for todays Retrotechtacular piece is the Bedford Levels, part of the huge area of reclaimed farmland in the east of England known collectively as the Fens. The Old Bedford River and the New Bedford River are two straight parallel artificial waterways that bisect the lower half of the Fens for over 20 miles, and carry the flood waters of the River Ouse towards the sea. They are several hundred years old, but next to the Old Bedford River at their southern end are a few concrete remains of a much newer structure from 1970. They are all that is left of a bold experiment to create Britain’s first full-sized magnetic levitating train, an experiment which succeeded in its aim and demonstrated its train at 170 miles per hour, but was eventually canceled as part of Government budget cuts.

A track consisting of several miles of concrete beams was constructed during 1970 alongside the Old Bedford River, and on it was placed a single prototype train. There was a hangar with a crane and gantry for removing the vehicle from the track, and a selection of support and maintenance vehicles. There was an electrical pick-up alongside the track from which the train could draw its power, and the track had a low level for the hangar before rising to a higher level for most of its length.

After cancellation the track was fairly swiftly demolished, but the train itself survived. It was first moved to Cranfield University as a technology exhibit, before in more recent years being moved to the Railworld exhibit at Peterborough where it can be viewed by the general public. The dream of a British MagLev wasn’t over, but the 1980s Birmingham Airport shuttle was hardly in the same class even if it does hold the honour of being the world’s first commercial MagLev.

We have two videos for you below the break, the first is a Cambridge Archaeology documentary on the system while the second is a contemporary account of its design and construction from Imperial College. We don’t take high-speed MagLevs on our travels in 2018, but they provide a fascinating glimpse of one possible future in which we might have.

It does make one wonder: will the test tracks for Hyperloop transportation break the mold and find mainstream use or will we find ourselves 50 years from now running a Retrotechtacular on abandoned, vacuum tubes?

Meanwhile across la manche, they were testing the aerotran, which avoided the drawbacks and expense of the maglev and ran on at first a plain poured concrete rail then more refined surfaces as the speeds went up. Sadly there was a bit of not-invented-here by the sncf who eventually adopted the tgv instead, which required special rails and cant run full speed inside populated areas. Although I can imagine a jet powered train might be quite noisy too :-)

Innovation era indeed.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A%C3%A9rotrain

Wow! La Manche is the French term for the English Channel!

The things I learn from Hackaday…

(And here I thought it had something to do with a man named Donkey Hotee)

But Cervantes was Spanish. I guess it is one of those times when a word is the same/similar in several languages?

Written similarly, but different. La manche (fr) = sleeve, la mancha (es) = stain, la manga (es) = sleeve, la tache (fr) = stain.

Les faux amis…

[the false friends…words which look alike, but mean different things]

Poo tube link , its in french at first, but the whoose noises and shots of the track after a few minute are in universal whooshy noises. Posting this because I always thought the aerotrain was a much more viable project than the maglev for the technology and investment levels of its era, but it was killed by politics, and the prototypes seemed to meet mysterious firey deaths.

https://youtu.be/5VvsxaaFNAs

Pathe english newsreel of the same…

https://youtu.be/p3CI82xVNig

Some of those prototypes were as gnar as it gets.

Aerotrain was a typical 60’s child that required full dose of cheap petrol and little to no respect for environment, much like concord in fact.

At least it was killed early, not much like the concord.

Yes, USA Amtrak and Russia each experimented with jet trains around the same time.

Thought: surprised none of those train sims have this particular category. Fantasy trains DLC.

And yet from the wikipedia link in the post you are quoting :-

Aérotrain S44 was a full-size passenger-carrying car intended for suburban commuter service at speeds of 200 km/h (in particular links between city centres and airports). It was equipped with a Linear Induction Motor (linear motor) propulsion system supplied by Merlin-Gérin.

Concord was iconic for me growing up of a different age and one of the things that made the era feel space age-y and want to become a engineer, and seeing it land was a big event locally that we would turn out and sit across the banks of the mersey to watch when it landed at Speke airport. Ditto the cross channel hovercraft. You never know, with new propulsion and storage systems their promise might yet be genetically carried forward into newer innovations for generations to come.

I’m keen on seeing the Sabre engines fly, but ESA is all but dragging their feet on the funding to develop the system into a viable platform.

Most likely because it’s a British invention and not French.

S44 still used V8 chevy engine to provide air cushion (they are hovercraft on tracks). What really killed them was the need to have new tracks end to end, where TGV can use normal railway up to 200km/h and dedicated railway to go at 300/350km/h (continuous rail with no cleats).

To put that in perspective, if your entire train can float on the power of one automotive engine, its way ahead of the fuel consumption and environmental destruction curve when compared against the likes of a deltic diesel etc.

And nowhere near the fuel consumption rates of a turbine engine which was your original reason of dismissal for the concept. And given they were propulsing the train along itself by electricity, its not a great leap to imagine the fan motor being powered by a electric motor also in future iterations.

The reason touted that the aerotrain was viable was the new trackway required was a simple poured concrete form. The TGV promised to run on the rail infrastructure of the time, so it was very much seen as the conservative sensible option, but in reality it cost massive amounts more in upgrades to that infrastructure to enable it to reach higher speeds in practice, costing significantly more than laying the new concrete track forms would have cost. Let alone the projects signed off for new build lines, then cancelled a week or two later due to politics.

I’ve rode the TGV as it is today, and fantastic a achievement given the constraints placed around it, sadly it was only given its head to run briefly at higher speed on one single stretch due to rail track conditions, speed restrictions around built up housing and other issues.

I think the maglev will come of age, and the time is right for it now, but you have to view things of the period through a lens of the time, not a current one. Same for concord and the cross channel hovercraft service.

[response to fresh install new username]

S44 wasn’t a “train” per se – it was a single car about the size of a smallish bus (32 seats total from the drawings, 44 passengers max from the accompanying text). And the V8 provided the air cushion only – propulsion came from a pair of linear induction motors at the rear.

So not so much ahead of the curve.

The British tried a gas turbine powered train also, in the form of the APT. The problem was that they gave the job of designing it to aircraft engineers rather than people with actual experience of trains. The prototype was timed at 161MPH, but by the time they put it into service it had been downgraded to Diesel Electric and could only reach 125MPH. It was also unreliable, so was eventually dropped.

Queue someone attaching the Simpsons “Monorail” song/episode…

Cue

Sorry, I’ve worked in broadcast for too long.

I used the wrong word, I guess that is why no one has linked it yet.

B^)

Wait…I got it…

(flips a few old timey switches…)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZDOI0cq6GZM

Ha! You there, eating the paste! That was awesome.

I think it’s misleading to call it a Maglev. This train was not levitated by magnets, only propelled by them.

Linear motors like that always have levitation forces. The issue is, the levitation isn’t particularily strong, and it cuts off as you cut the power to the motors to coast, so it needs a backup system that keeps it afloat and well off from scraping along the sides.

fast but on normal tracks https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Passenger_Train

I think theres a model available

Sadly, that was also cancelled, and ended up as a cafe at Crewe station.

The “Railworld” link opens to a suggestion to go to

http://www.railworld.org.uk/

instead.

Thanks, updated.

“the Bedford Levels”,”the Fens”,”The Old Bedford River and the New Bedford River”,”River Ouse”

So much English geography yet to learn!

And actually it’s The Great Ouse river… The Ouse passes through York in North Yorkshire, many miles to the north :)

There’s a few Ouses (I grew up by one in Sussex). It’s one of those names that just means “river” or similar, along with (from memory Avon, Wey, Severn and others)

“…..across the Ouse to the Waveney…..This is Radio Norwich….”

For US or non-British readers, Ouse is pronounced “ooze”, not “owse” or whatever else might be intuitive ;-)

Thank you!

(of course, you could be “pulling our leg”, but I wouldn’t know that)

B^)

I was wondering if it was pronounced like an East Ender pronounced “house”.

B^)

No, that’s ‘aarse’, ‘ouse is a Northern thing.

“will we find ourselves 50 years from now running a Retrotechtacular on abandoned, vacuum tubes?”

Yup, we will. Like has been said before It doesn’t scale well especially at longer distances. Take a look at the issues plaguing long distance pipelines and you can see some of the challenges present in building long tubes thats must retain structural integrity.

The Hyper Loop tube will take you out to the launch complex, where you board a BFR. ;)

Alaskan pipeline. Of course not every one has to deal with permafrost. And if one looks at a map of the underground pipelines that run throughout the US, we’ve done surprisingly well.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_pipeline_accidents_in_the_United_States_in_the_21st_century

“This is not a complete list of all pipeline accidents. For natural gas alone, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), a United States Department of Transportation agency, has collected data on more than 3,200 accidents deemed serious or significant since 1987.”

In other words, over 100 significant leaks a year.

Which is not a complete list and only applies to natural gas alone, not any of the other variations of hydrocarbon products that are put through pipelines. Now when you consider that any leakage in the Hyperloop would significantly slow down the actual trains combined with the mitigation devices required (such as airlock sections or thermal expansion mechanisms), those factors would significantly increase the costs with out providing the benefits of travel faster than current open air high speed rail. that is why we haven’t had and wont have anything like the hyperloop, even though the idea was patented over 50 years ago in the US https://patents.google.com/patent/US2511979 and also considering that the idea has been around much longer than that. The problem is that any sections that need to be repaired have to then run at a much slower speed which removes any benefit and when combined with a more complicated system increases the costs. In the end there are two options for the hyperloop, above or below the ground. Above the ground there is the issue of thermal expansion which would require complex sealing mechanisms or pipeline expansion loops. Those are mitigated by burying the tubes but then you increase the cost of repairs and inspection. Call me a skeptic, but i just dont it happening when it comes to human or goods transportation over long distances. Much like supersonic flight sometimes

the cost/benefit just doesn’t balance out enough to make it a profitable commercial enterprise.

“We don’t take high-speed MagLevs on our travels in 2018”? what about the (Chuo Shinkansen) in Japan or the Transrapid in China?

Under construction until 2027.

The Transrapid in China is a bit of a political turkey, since it’s so short that it can only reach top speed for 50 seconds before it already has to start braking, and it costs ten times the price of taking the regular train so the train only runs at 20% capacity and the company is running at 1 Billion RMB loss to prop it up. Same reasons why the original track in Germany got demolished.

There’s an alternative Shanghai–Hangzhou high-speed railway that takes passengers the same distance in 45 minutes vs. 8 minutes for the maglev + 20 minutes on bus to actually reach the city.

The German Transrapid test track is not yet demolished – here is a video from 2016:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h_oCU1OUgHw

If that was here in the States, it would be all covered with grafitti.

…inside and out.

With a couple of mounldy matresses and lots of burn marks and needles inside.

My understanding from the locals was that the transrapid was built fully with the intention of being expanded by an overly ambitious “company”.

The alignment in Pudong suggesting where it was supposed to carry on to – Shanghai Hongqiao

But as you say, polticial will, the wish to build the metro (which is unbellevable overcrowded) sealed it.

It was perfect as an airport to airport and station link.

I was also told that different times of the day it runs at different speeds.

For two reasons. One, electrical consumption, and the second more for the summer, the expansion of parts of the track & trains in the heat. Now the former I believe. The latter could well be urban legend, but this was coming from locals employed in engineering fields – but not maglevs :)

The sort of thing the UK should be looking at for heathrow / gatwick expansion.

Fast transit between the two sites. Euro/internal hub and intl hub.

Instead we get HS2. Which we don’t need. Is old, slow technology, not even TGV speed.

No one really wants (except that poltical will once again) and will cost far far far too much money.

And cost far more than a current train ticket yet only be 20mins faster from the north to south.

The only hope for it not getting built is that all the major pet contractors of the government are going bust.

Always a positive :)

What might be more efficient is running on rubber tires to get up to ram air levitation speed, then use electric ducted fans picking up power via induction. When rolling through cities, slow down and use the wheels.

The Seattle Monorail uses rubber tires (tyres -Jenny)

What do conventional monorails in Japan use, e.g. Osaka? From the videos they appear to have something like rubber tyres too? They are a city transport so they do not need to be insanely fast.

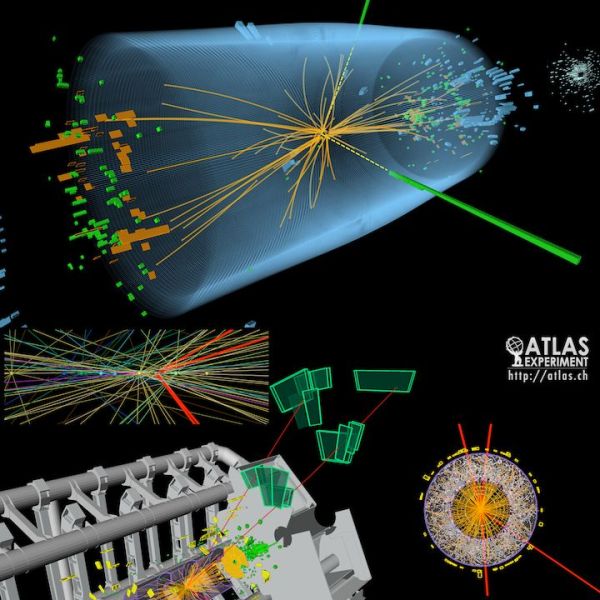

I’m surprised that the article didn’t mention British engineer Eric Laithwaite who invented the AC linear motor and “maglev” system. There is an excellent video of him demonstrating the development process here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OI_HFnNTfyU

“The future was better in the past”

Quote from me, whenever I see cool predictions of the future, made in the 40, 50 ans 60’s, after that the future started looking gloomy…

I know what you mean. My theory is that the artists impressions of the future were better in the past, either injecting or reflecting more optimism, before ‘modern’ computer-aided graphics came in. (picture at the top of the article is a good example).

I was also told that different times of the day it runs at different speeds.