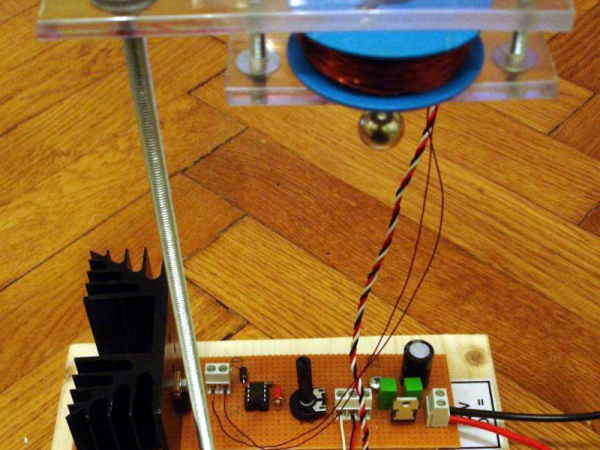

[Stoppi] always has exciting projects and, as you can see in the video below, the latest one is a very simple magnetic levitator design. The design is classic and simple: a 5 V regulator IC, a Hall effect sensor, a 741 op amp, and a MOSFET to turn the electromagnet on and off.

Sure, there are a few passive components and a diode, too, but nothing exotic. The sensor normally presents 2.5 V of output. The voltage rises or drops depending on the polarity of the magnetic field. The stronger the field, the more the voltage changes away from the 2.5 V center.

The op amp acts as a comparator with a potentiometer setting the trip point. As the ball moves up towards the coil, the voltage increases, triggering the comparator, which turns off the FET. With no current through the coil, there’s no more electromagnet, and the ball starts to fall.

Of course, as the ball falls, the voltage from the sensor also drops, and this eventually turns on the electromagnet. The ball eventually reaches a relatively stable position.

This is one of those cases where a simple analog circuit might work better than a digital one. Or make it hard on yourself and use an FPGA.

Continue reading “Simple Magnetic Levitator” →

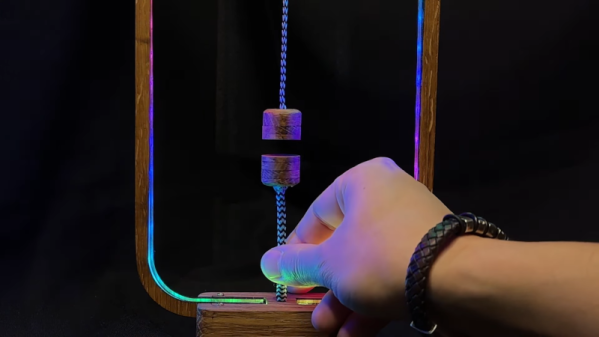

This levitator is USB-powered, and typically draws 1 W to 3 W to levitate masses between 10 g and 500 g. The base can provide 3 V to 5 V inductive power to the levitator to the tune of 10 mA to 50 mA, which is enough for some interesting possibilities, starting with the lights and motors [Jonathan] has tried.

This levitator is USB-powered, and typically draws 1 W to 3 W to levitate masses between 10 g and 500 g. The base can provide 3 V to 5 V inductive power to the levitator to the tune of 10 mA to 50 mA, which is enough for some interesting possibilities, starting with the lights and motors [Jonathan] has tried.