The phrase “Hindsight is 20/20” is one of those things that we all say from time to time, but rarely have a chance to truly appreciate to the fullest. Taken in the most literal context, it means that once you know the end result of a particular scenario, you can look back and clearly see the progression towards that now inescapable endgame. For example, if you’re stuck on the couch with a bad case of food poisoning, you might employ the phrase “Hindsight is 20/20” to describe the decision a few days prior to eat that food truck sushi.

Then again, it’s usually not that hard to identify a questionable decision, with or without the benefit of foreknowledge. But what about the good ones? How can one tell if a seemingly unimportant choice can end up putting you on track for a lifetime of success and opportunity? If there’s one thing Michael Rigsby hopes you’ll take away from the fascinating retrospective of his life that he presented at the 2018 Hackaday Superconference, it’s that you should grab hold of every opportunity and run with it. Some of your ideas and projects will be little more than dim memory when you look back on them 50 years later, but others might just end up changing your life.

Of course, it also helps if you’re the sort of person who was able to build an electric car at the age of nineteen, using technology which to modern eyes seems not very far ahead of stone knives and bear skins. The life story Michael tells the audience, complete with newspaper cuttings and images from local news broadcasts, is one that we could all be so lucky to look back on in the Autumn of our years. It’s a story of a person who, through either incredible good luck or extraordinary intuition, was able to be on the forefront of some of the technology we take for granted today before most people even knew what to call it.

From controlling his TRS-80 with his voice to building a robotic vacuum cleaner years before the Roomba was a twinkle in the eye of even the most forward thinking technofetishist, Michael was there. But he doesn’t hold a grudge towards the companies who ended up building billion dollar industries around these ideas. That was never what it was about for him. He simply loves technology, and wanted to show his experiments to others. Decades before “open source” was even a term, he was sharing his designs and ideas with anyone who’d care to take a look.

It Never Hurts to Try

A recurring theme throughout Michael’s talk is the way that events occasionally unfold unpredictably, and that sticking to the “safe” route can sometimes take you out of the running for potential opportunities. Even if you aren’t sure something is going to work out in your favor, give it a shot anyway. At worst you’ll waste some time, but if you’re lucky, that shot in the dark might just end up paying off.

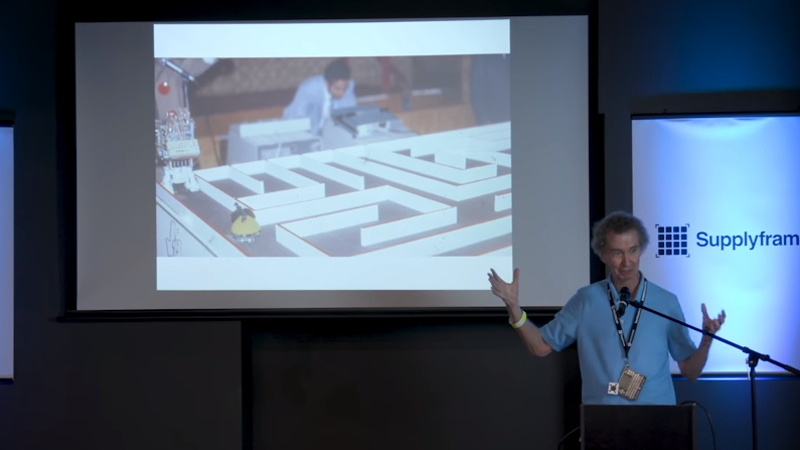

As an example, Michael tells a story about the robotics contest at the National Computer Conference in New York City. He had received a free ticket for himself thanks to his entry into a robotics contest which was happening at the Conference, but the cost of buying a ticket for his wife was more than they could afford. At the last minute they assembled a robot for his wife to enter which was little more than a bump-and-go car with a cute fabric mouse body.

As an example, Michael tells a story about the robotics contest at the National Computer Conference in New York City. He had received a free ticket for himself thanks to his entry into a robotics contest which was happening at the Conference, but the cost of buying a ticket for his wife was more than they could afford. At the last minute they assembled a robot for his wife to enter which was little more than a bump-and-go car with a cute fabric mouse body.

The mouse wasn’t meant to be a serious entry, it was just a hack to get her in the door for free. So it was no surprise when it was eliminated immediately for failing to navigate a maze. Michael’s robot ended up not faring much better, as his competitors were better funded and more advanced. But when the television news cameras started rolling, their story ended up being more interesting than the robotics competition itself. The two worst performing entries in the contest ended up being the ones shown on the news, getting Michael and his wife widespread attention.

Forge Your Own Path

Michael also has some thoughts on the adversity that creative individuals often face when they refuse to take the road most traveled. He says there were several times when people told him that his latest idea wouldn’t work and that he was wasting his time. He admits that occasionally they were right, and that you shouldn’t necessarily ignore established wisdom outright. But sometimes it pays to follow your instincts and see where it takes you.

Michael also has some thoughts on the adversity that creative individuals often face when they refuse to take the road most traveled. He says there were several times when people told him that his latest idea wouldn’t work and that he was wasting his time. He admits that occasionally they were right, and that you shouldn’t necessarily ignore established wisdom outright. But sometimes it pays to follow your instincts and see where it takes you.

When Michael first saw the Texas Instruments Speak & Spell toy in stores, he was so impressed with it that he took it home and tried to figure out how it worked. He wrote an article for Byte magazine with his theories on how the device functioned, which was met with criticism from readers who claimed his analysis was flawed. But soon after he received a phone call from one of the toy’s designers congratulating him on his reverse engineering. A few weeks after that, he was contacted by a publisher asking if he’d be willing to write a book on the subject. Not bad for a flawed analysis.

If you’ve ever wondered if it was worth chasing down that wild idea or putting together a project that may or may not work, Michael Rigsby wants you to know you aren’t alone. Take a chance, and see where it leads you. Who knows? Some day in the distant future you might end up telling a packed room all about it.

Is that EV named Carman Electric?

Maybe Karmann Electra

Tom, be honest, did you just finish A Series of Unfortunate Events on netflix? That first paragraph is being read by Patrick Warburton in my head.

I really appreciated that talk.

It’s so easy to be an arm-chair critic without actually doing anything. Kudos to you guys and gals who actually get out there and do stuff.

I left a senior position at a major company to start the first of several start-up that mostly didn’t take off and have a couple of observations. One is that there is a lot of luck involved. In a couple of cases, chance events killed the opportunity. That is why you need to be persistent to succeed. More importantly, timing is critical. Being too early is just as bad as being too late. My first start-up in 1999 was intended to address the issues around Internet identity, privacy and security, but at that time just about nobody cared about those things so we couldn’t gain traction. I think that may be a significant problem with hackers leaving their jobs to create start-ups. Often hackers are at the “bleeding edge” and the public and, more importantly, VCs simply aren’t there yet. Unfortunately, there is no reliable way to know when the timing is right other than presenting your ideas to the right audiences and seeing if they get it. Even then, you have a dilemma. Will you get there with persistence or do you need to have the humility to admit that your idea is not the right idea at the right time?

Having said all that, I reckon I broke even overall on my start-ups and the experience was great. So, if you can afford to lose a year or two of income, I would say go for it.

And your health insurance.

Not everyone lives is the USA where this is an issue, maybe its a good idea to come to europe to be safe ;)

See: http://www.robotdalen.se/en/technological-solutions-health-care-sector-and-elderly

I love how down to earth he is, I’d love to just chat about random stuff with him. My limited experience matches pretty closely with the message Michael gave. I’ve had things I thought would take off that just sort of fizzled out (but were a great source of learning nonetheless), things that I only did because I was bored that went on far longer than I thought they would and even turned into a side source of income. I cant predict what tomorrow holds, but keeping a network of connections with as many people as possible in different areas has never led me astray. Take every chance you can, be persistent, and trust your gut. Never stop being curious and growing. I’m still pretty young and while my life has been far from perfect I really cant complain much with how things are at the moment.

Definitely very positive message with this presentation. It’s nice to see that not all the talks at the supercon are of the mind-bending complexity type. It’s good to balance it out with something like this, keep people from getting burned out.

At 68 I am just now beginning to believe in something loving and greater me and at 68 I can and will succeed at whatever I put my mind to.I have come to believe.

Thank you Micheal

Interesting my hacking paralleled with Michael’s journey, in fact I had read his articles back in the day.

My first shock as an inventor/hacker was that the idea person and inventor doesn’t get the money, but it is the business person that can bring it to the market successfully that gets the money. We engineers love the idea and the process of inventing but that is so far from bringing it to the market.

I have several unsuccessful attempts under my belt, doing one now on a medical device and now have a team around me three of them doctors and others business people. All to say the idea and proto-type was easy, bringing it to market is so so so hard.

Maybe when it successful I will do an HAD article about the journey.