While it isn’t quite universal, a lot of people enjoy a glass of wine now and again. But the world faced a crisis in the 1800s that almost destroyed some of the world’s great wines. Science — or some might say hacking — saved the day, even though it isn’t well known outside of serious oenophiles. You might wonder how biological hacking occurred in the 19th century. It did. It wasn’t as fast or efficient, but fortunately for wine drinkers, it got the job done.

When people tell me about new cybersecurity threats, I usually point out that cybercrime isn’t new. People have been stealing money, tricking people into actions, and impersonating other people for centuries. The computer just makes it easier. Even computing itself isn’t a new idea. Counting on your fingers and counting with electrons is just a matter of degree. Surely, though, mashing up biology is a more recent scientific advancement, right? While it is true that CRISPR can make editing genes a weekend garage project, people have been changing the biology of plants and animals for centuries using techniques like selective breeding and grafting. Not as effective, but sometimes effective enough.

The Wrath of V. Vinifera

Although wine is made throughout the world, there’s an unmistakable association with France and wine. When Europeans came to the new world, they often brought grapes. While grapes grow just fine in America, most of the native varieties are not great for making wine. Pretty much all of the wine you are likely to drink uses a single species of grape: Vitis vinifera. Because winemakers have used this grape for centuries, they know how to get the flavors they want out of it. There are native American grapes that will make wine, but they don’t make up much of the total wine consumption of the world.

For this reason, colonists would often plant old-world grapes. However, some people like experimenting with the new world grapes and — as you might expect, some vines found their way to Europe.

The Root of the Problem

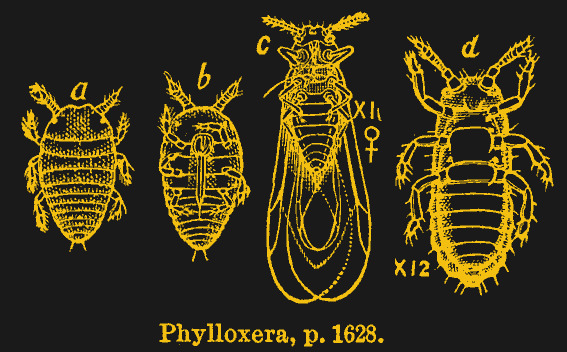

In the mid-1800s, there was no real regulation on bringing live plants in or out of most countries. Biologists searching for interesting hybrid grapes for wine would obtain American plants as subjects. If it had just been a vine or two, that wouldn’t be very noteworthy. However, the vines had an unwelcome visitor: Phylloxera — a type of aphid.

These are essentially aphids that attack a grapevine. These didn’t exist in Europe, apparently and grapes from the Americas were resistant to them, at least to some degree. But colonists tried and failed to grow European vines going back to the 16th century. They didn’t know why, but it became widely known that vinifera would not grow in most parts of the Americas, with California being an exception because the aphid had not made it that far west yet.

Phylloxera aphids have a nose with a venom tube that poisons the plant as the bug sucks out its sap from the roots. By the time the plant is dead, the aphids have pulled up stakes and moved to a new plant. So digging up a dead plant usually doesn’t show any infestation, which may be why the colonists didn’t understand what was killing the plants.

Phylloxera aphids have a nose with a venom tube that poisons the plant as the bug sucks out its sap from the roots. By the time the plant is dead, the aphids have pulled up stakes and moved to a new plant. So digging up a dead plant usually doesn’t show any infestation, which may be why the colonists didn’t understand what was killing the plants.

But back to France. In 1863, a vineyard in the city of Pujaut had plants die from an unknown cause. Soon after, an unknown plague was ravaging vineyards throughout France, but it would be 1868 before scientists started to understand it was the tiny little bug. Even then, they were not sure until 1870 when [Victor Antoine Signoret] confirmed it.

Despite compelling evidence, some people thought the insect infestation was secondary to some other root cause. One group of growers tried various pesticides without much luck. Some put toads under each vine, hoping they would eat the bugs. Over 40% of France’s grape vines fell to the blight and the French economy lost an estimated 10 billion Francs.

What finally proved workable was to perform a little 19th-century biohacking. European vinifera vines were grafted to roots from vines from Texas. The bugs attack the roots, but these roots were resistant so the bugs didn’t want them. Meanwhile, the Vinifera fruit would grow like they always did even attached to the resistant roots.

Aftermath

There’s still no remedy for Phylloxera, and vines that are not grafted are protected carefully. Naturally, people argue over the taste of grafted wine vs self-rooted wine, but the overwhelming volume of wine comes from grafted vines. Not all roots did as well in European soil, but Vitis riparia worked best. Today, the roots may also come from Vitis aestivalis, Vitis rupestris, or Vitis berlandieri.

You might think the debate about taste is nitpicking, but there are actual physical differences with grafted vines. For example, grafted Zinfandel grapes often grow grapes with more size variation on a given plant when compared to the uniformity of a non-grafted sibling. Also, some roots draw more nitrogen and potassium from the surrounding soil than the original roots which can change the soil pH. As the soil chemistry changes, so might the taste of the wine. Some argue that the difference isn’t so much the roots, but the age of the vines, since grafted vines tend to be younger. Like most matters of taste, though, it is hard to say with certainty. Most experts agree, however, that if there is a difference, it isn’t a great difference.

The video below claims that scientific testing says there’s no difference. The video has a pretty good lecture on the topic. That video mentions 75% of French production was ruined by the bugs — our sources say 40% but still a big hit either way.

Biohacking

We think of biohacking as a modern pursuit, but the reality is it’s been going on for a very long time. Breeding dogs or plants or cattle is really biohacking. It is just slow, low-tech biohacking. I can’t help but wonder, though, just as biohacking and cybercrime has gone on for many years before the digital age, what other things out of history can be done better by infusing it with technology?

Of course, if wine is too refined for your palette, there’s always beer and that’s been gene edited using CRISPR. Even World War II has an old fashioned biohacking story that we’ve covered before.

Nice article. One nit: Victor Antoine Signoret must have been 1870, not 1970.

As far as I remember, also the great Louis Pasteur was involved in that fight.

Cf. https://www.thewinestalker.net/2017/04/pasteur.html

Finger memory is a terrible thing. Thanks — fixed now.

The current bug de jour a giant leafhopper came in to the US from the same container port as the brown marmorated stinkbug. Hops and grapes as well as much forest growth and vegetables, are on the chopping block. No enemies but us. Oddly it is fondest of it’s home tree, the old invasive stinktree, the tree of heaven, Ailanthus altissima. So we may get rid of our stinktrees like we lost the ash trees.

It bugs me, people who move living things around on the planet.

Living things moving living things around everywhere. The horror!

:^)

It’s just rotten grape juice. Smells and tastes rotten because it is rotten. A whole culture built around carefully made garbage. Dunno how anyone can drink it without vomiting, how they override their reflex to spit out what their tastebuds should be ‘saying’ “Hey! What are you doing! This is some rotten crap! Spit it out!”.

If you’re tastebuds are telling you the wine you are drinking is rotten then the problem is with the wine you are drinking, not wine in general! Fermenting isn’t rotting.

A heavy bordeaux is not for everyone (I certainly don’t like it) but a light sweet white like a Riesling or less heavy red like a Frankovka certainly doesn’t taste rotten (Or smell rotten).

Did you ever had jogurt, cheese, tea, bread, etc.? A world without fermentation would be impossible, just sayin’ to feed the Troll.

Kimchi looks like the stuff at the bottom of my compost bin, but damn if it isn’t delicious.

Remember when Gollum told off Sam for ruining his fish by cooking it?

Or in “Ringworld”, where a carnivorous alien tells a human attempting to cook his food “The meat is not fresh, but cremation is not the answer.”

“A whole culture built around carefully made garbage” the same could be said for clothes, cars, phones, computers, software, and so on and so forth.

In essence what you have just said is: ” why doesn’t everyone like the exact same things i like and have the exact same opinions that i have” to which the answer is: the world would surly be a entirely boring place and civilization would more than likely collapse because of a lack of diversity.

Factually incorrect. Subjective interpretation at best.

If you want a really good rotten wine try Tokaji, loves me some of that noble rot!

When we were in Belgium, we were walking around a field of potatoes near Waterloo and we spotted the plants were infested with ugly pink larva and striped beetles. It was only when we got back that we realised they were the dreaded Colorado potato beetle, introduced into Europe from the new world in about 1920 and there are no current pesticides capable of controlling it. Which just goes to show, this goes on a lot

Potato bug? Oh there are pesticides to deal with it. But some other methods are effective, especially for smaller plots.

For example, my parents are collecting them by hand (!) and throwing them into a jar of oil where they drown. :) They don’t want to use pesticides.

I believe that they are very adaptable to pesticides and there are more effective measures based on their life cycle. I can say they are about the ugliest bug I have ever seen

Pfeh. Folks, chill down. One person disliking wine is just one competitor less :-)

Also… fresh cheese: rotten milk. Roquefort: doubly rotten milk. Yummm…

http://wlu18www30.webland.ch/wiki/images/c/cc/Biohackers_final.png

We have always been biohackers.

We hacked grass into grain, grain into beer. We hacked wolves into dogs. Ox into cow. Milk into cheese…

Auroch not Ox

I remember, back in the 80’s, California ironically set up border roadblocks to help prevent the ingress of the dreaded “fruit fly”… You could buy dates at a roadside stand and a mile further along have them confiscated.

How did they set up border roadblocks ironically?

A Connections 3 episode on this very topic (and many related topics, including early forms of secure currency)

In Italy andin most european contries, making wine using american grapes is illegal since the resolution of the Philossera case.

The reasons of this ban are the commercial protection of our vitis vinifera varietis and the level of toxic methanol in the wine from american grapes. Someone make some of this illegal wine just for personal use, but there isn’t a illegal market because this wine tastes too sweet and too much different from the regular wine.

Not that I’m into the bible, but genesis 30-39 shows a scientifically illiterate author trying to describe selective breeding of cattle, that apparently was quite effective and a total mystery to everyone but the breeder. I think it’s the oldest known description of selective breeding/biohacking.