When Kenyan engineer [Aloise] found out about the health risks of household air pollution, they knew there had to be a smart solution to combatting the problem while still providing a reasonable source of energy for families cooking without the luxury of cleaner fuels. Enter OpenHAP, a DIY household air pollution monitor that provides citizen scientists and researches the means to measure air particulates in developing countries.

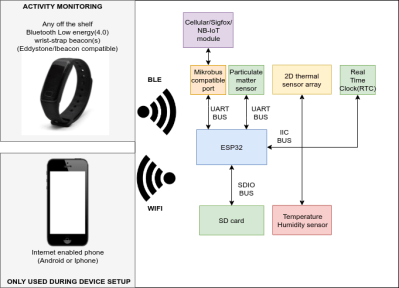

The device is based on an ESP32 communicating with a ZH03B Particulate matter sensor over UART; a DS3231SN real-time clock (RTC), temperature and humidity sensor, and MLX90640 2D thermal sensor array over I2C; and wirelessly sending the data received to a Bluetooth low energy wrist-strap beacon and an Internet enabled phone. The device also uses a TCA9534 GPIO expander to control the visual and auditory notifiers (buzzers and LEDs) and to interface to a SD card.

The project uses the libesphttpd project modified for the ESP32 for the webserver, which is used to stream data to a mobile handset or computer using the WiFi capabilities of the ESP32. The data includes real-time sensor information, system status, storage media status, visualizations of the thermal array sensor data (to ensure the camera is facing the source of heat), and tag information to test the limits of the Bluetooth tag with regards to distance.

Power input is provided through a Micro-USB connector, protected with a TVS diode and a Schottky diode in series to prevent reverse power flow.

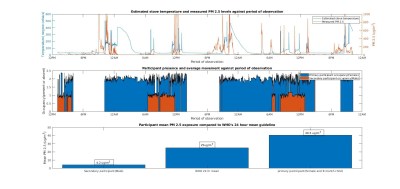

The project was tested in two real-life scenarios: one with a household in rural Kenya and another with an urban low-income family of four. In the first test, the family used a three stone open fire stove. A FLiR thermal camera captured the stove temperatures, while a standard camera was enough to capture the high levels of smoke inside the kitchen. The readings from OpenHAP were high enough to exceed the upper detection threshold for the particulate sensor, showing that the woman cooking in the house was receiving the equivalent of 8 cigarettes a day, about 8 x the WHO’s recommended particulate levels.

Within the second household, a typical energy mix of charcoal briquettes and kerosene was typically used for cooking, with kerosene used during the day and briquettes used at night. The results from measuring pollution levels using OpenHAP showed that the mother and child in the household regularly received around 1.5 x the recommended limit of pollutants, enough to lead to slow suffocation.

Within the second household, a typical energy mix of charcoal briquettes and kerosene was typically used for cooking, with kerosene used during the day and briquettes used at night. The results from measuring pollution levels using OpenHAP showed that the mother and child in the household regularly received around 1.5 x the recommended limit of pollutants, enough to lead to slow suffocation.

There’s already immense potential for this project to help researchers test out different energy sources for rural households, not to mention the advantage of having a portable low-energy pollution monitor for citizen scientists.

Kerosene not a particularly good fuel.

Biogas might be better.

https://www.climatetechwiki.org/technology/biogas-cook

Probably natural gas would be even better from the point of indoor air pollution. But this site seens to be an environmentalist site, they obviously have other priorities. I expect less sulfur content in natural gas than biogas. But kerosene is still better then wood or charcoal.

In the end it depends on the availability of resources (biological waste or fuels). If somebody has excess biomass than the biogas is a good thing.

Nice project.

But wouldn’t just building better and more efficient stoves with the same money than building fancy toys be actually useful?

If the point is to reduce particulate and soot emissions?

Same deduction here :) great to see I’m not alone

x2

I think this would be an excellent way to study the system, serve as a teaching tool, and to help raise awareness. In doing that, I think it could be used to help develop ways to modify the system.

When you have a hammer, or in this case, when you’re an engineer in an uptown electronics company, every problem looks like it needs a an electronic gadget.

Remember the OLPC project? $100 buys a lot of pens and notebooks…

Household air pollution is one of the least understood issues. Drawing parallels of this to the OLPC project bears no correlation. Please see my corrections/additions below to your comment:

1. Household air pollution is one of the most misunderstood problems. This project is to better understand the problem on a social level.

2. We are not giving/selling OpenHAP units to the those at the BOP, rather this is to help in research as to which social classes should better and more efficient stoves be targeted – Urban/rural etc.

3. The data is also useful to determine cultural biases and habits that may have an influence to pollution, from the data captured by the OpenHAP unit. It is very difficult to get this data by face-face interviews.

I think we know the by products of fossil fuels. Rural households mostly use charcoal and wood for cooking and their pollution by products are well known. Do we really need such a gadget when we know very well the pollutant contents?! Air Pollution should be avoided whether in small or large quantities. Knowing the pollution sources i.e. from the fuel, mitigation factors should be initiated ASAP.

Hi Simon,

Great to hear from you. Didn’t see you at the workshop. Your question(sources) however is covered. Please read the project description keenly. An excerpt is below:

While bold steps have been made so far in having some populations in Asia, Africa and Latin America move from unclean fuels to relatively cleaner fuels, progress is relatively slow due to a knowledge and technology gap in developing countries on how to generate data quickly on the causes of household air pollution within their own contexts( Is it human behaviour/stove technologies used/ Types of fuels used or a complex combination of the three that is the cause )

Just replacing is good. Having usable data on how much you improved situation is better. With that pollution monitor you can try several solutions and find the one which is best. Without data you “probably” helped. With data you know how much you helped and how bad the situation was.

Very correct!

Alois here, Great question! What you mention(efficient stoves) is happening, but the question has been where to target them at as opposed to a blanket approach and to clearly answer your question do see my corrections/additions below to the above article:

1. Household air pollution is one of the most misunderstood problems. This project is to better understand the problem on a social level.

2. We are not giving OpenHAP units to the those at the BOP, rather this is to help in research as to which social classes should better and more efficient stoves be targeted – Urban/rural.

3. The data is useful to determine cultural biases and habits that may have an influence to pollution, from the data captured by the OpenHAP unit. It is very difficult to get this data by face-face interviews.

Sounds good!

when particulate and soot are “normal”?

different topic, same sociological mechanism:

my parents dismissed of radon gas danger as a “hipster topic, much like feng shui”.

Until I had them carry a borrowed geiger counter into the basement. I will never forget my dads face when he lowered the then screaming device near the pump sump (deepest point of the basement).

now we have a basement ventilation system, a dry and cool basement without radiation danger. central heating and ventilation system both suck their air from the top of the pump sump, so any radon gas should be sucked out of the house.

In an environment where everybody walks daily through smoke (and many people smoke on top) it is “normal” as in “not particularly dangerous”. Much like living in Beijings smog since ages – everybody did, so it has to be “normal” – right?

You need some small shock to alter things, to fight this kind of “normal”, even more so because “not falling ill somewhen later” is no instant reward.

Beijings Olympic games brought the first smog free days in decades, and if some fancy diagram can trigger changes in Africa then why not?

My current interest in heat recovery ventilation has been triggered by me dabbling with co2 and o2 sensors, monitoring my bedroom. same principle here…

Also, I can only recommend to occasionally video your own’s sleeping. It makes you changing your sleeping habits.

So we can’t get anyone to believe in what’s dangerous without a machine that goes ‘beep’. Sounds like an education problem more than a technological one.

I’m assuming the goal is more to be able to actually point people to the problem. Sure they “know” smoke is bad for them, but I can imagine if all you can afford is 3 stones and some wood for your cooking you have more pressing issues than the smoke of the fire. So you just “don’t think about it” . Because that is what humans do. Actually showing the data to people and explaining the effects could be the incentive to change the stove layout to reduce emissions or make the large investment to get something better.

Showing the data without providing an alternative heat source will change nothing. Why? Because regardless of how bad running an open fire in your living room is, for most it is a preferable alternative to freezing and/or starving. If people only have ‘3 stones and some wood’, just what kind of home infrastructure investment do you think they can make?

Was also my thought at this theme. “A normal camera was enough to see the high levels of smoke” – and also the naked eye. An open wood fire in an enclosed space is a bad idea, that can not be changed by any kind of monitoring.

Yes, this. For less than the cost of sensors, electronics, electricity, and computers for data analytics of the data, give the poor woman some education about not poisoning her home and family and a wood gassification stove and a proper chimney or flue to put her newfound awareness into practice.

I totally agree that the cause is honorable, but honestly… kerosene and coal do not necessitate a connected sensor to deduce there will be air pollution, and the people suffering this pollution will not afford this

The solution there is not pointing the cause and the effect, but to prevent it, for instance by mass producing a lasercut stove cooker which would allow correct combustion and exhaust and could be produced from anything like fridge panels or any recycled steel foil…

+1

But more than that, just teach people to build a better model of stove, with available materials ( brick/clay/cement ).

Or those models that are very efficient and built from metal sheets.

But mostly, TEACH the people to build the better things, instead of just dumping one more technological thingamajig / technobabble over them. They already know the smoke is bad for them. Just showing them a better way to build that stove ( and I´ve seen the most important point is in the dimensions/construction of the chimney ) will make wonders.

When you ‘just add a flue’ you significantly increase the size of the apparatus and the amount of material needed to make it. Compared to the very small and cheap pot stands pictured you’re talking about a much more expensive, large, immobile piece of equipment. One that would take longer to heat up, be more difficult to clean and require more fuel.

Great comment Shrad! There are already preventive methods existing with regard to efficient stoves(Depending on stove efficiency parameter in question) – This project is more on both a technical and social monitoring level to get data on the cause and give visibility on improvement of the issue.

The goal is that different technologies can be tested and the monitor can show a decrease in pollutants over time together with the social changes in the household – which have a direct impact, that is the USP!

My issue with the topic is, that it is like having a sick child with a fever. The cause of the fever is already known – it’s the flu – and the cure for the disease is likewise known. Good nutrition, rest and sleep, and the fever will be gone in 3-7 days.

If one has a thermometer at home, it seems prudent to check the child’s temperature every few hours to see if they’re improving – but in reality this does nothing to help the child. The fever rises and falls as it will regardless and the main effect and purpose of the thermometer is to make the parent feel like they’re doing something – to put the parent at ease.

Same thing here. It is already known that having open fires and kerosene lamps indoors produces unacceptable levels of pollution, and the remedy is improving the social conditions to the point where people don’t need them. The diagnosis is obvious, and the cure is obvious. As soon as people can afford to use anything else, the problem solves itself. Measuring exactly how much pollution there is, or whether it is getting more or less, does not improve the social conditions – it merely makes it feel like you’re helping.

That’s why spending much resources on developing and deploying high tech gadgets like this is a waste. It serves merely to employ people to feel like they’re helping, while actually they’re using the resources that would be better spent on actually improving the social conditions. This is like Al Gore environmentalism, where the point is “raising awareness” rather than doing anything about it, whether for money or just to feel better yourself.

Your 1.2.3. points do not address this criticism at all, and apparently HaD is on a censorship spree again to suppress any dissenting opinion. Shame.

I think for these people plans to cut this yourself with basic tools could be more helpful. They do not have access to lasercutters, but perhaps somebody there has an angle grinder or a metal saw. You can not give all the poor people a stove as christmas present.

CO2 and CO sensors might be a very good addition to this.

We noticed this when one of the areas we tested had a high CO poisoning risk due to improper ventilation, looking to implement it into the next iteration! Thanks

This is not a “solution”, this is ” monitor the problem”

I could not disagree more with most of the comments here. These tools are very important in my opinion.

It is actually very important to measure how much difference an improved stove is making compared to a traditional stove. There are a lot of solutions that look good in a lab setting (ie: they emits a lot less smoke) but their performance in the field is not as good.

You can not just assume that your improved stove will work in the field, you have to make measurements.

That will save a lot of money because right now too much money is wasted on “solutions” that does not have a real impact in terms of reducing exposure to smoke. It is important to measure exposure in the field to focus the limited findings of the sector on solutions that really works.

We owe it to the 3 billions people that still use solid fuel in the world today leading to 2 millions of premature death per year.

Thanks so much Alois for your work on this.

Thanks for your perspective! Clearly some comments here have gone off in a tangent and I choose not to go down that rabbit hole. This sums it up very clearly as to the objectives. Glad you see value.

WTF is about us “Western World People” that makes us so prone to throwing more technical complexity (& usually bureaucracy) at everything?

The annoying cough, burning eyes and layer of soot on everything in the house, isn’t a sufficient monitor?

Yes, I’m in the camp that says “fix the problem, not the blame”

Anyone who would be amenable to using this in their house, is most likely already very cognizant of the problem(s) for above listed reasons.

So ditto on putting resources towards the solution instead of more unneeded complications

This is actually the educational device through witch someone would be learning about real world contamination levels in their surroundings.

You recognized it correctly, it truly is an education problem. And with proper data, that gets measured in situ, people learn about pollution in a direct manner.

FWIW, a rocket stove can be built with ZERO tools and is up to ten times more efficient than even a good wood stove, and smoke & CO emissions drop to almost ZERO within ten minutes of starting the fire. How well does it work? One stove can use only three pounds of twigs to heat eight gallons of water to a boil. As well, a (well-insulated) chimney can reach 2000F or so.

Amazing what just grabbing the data can show, and how that can be used to make much more impact later, with informed design.

There was a very similar project written up in a 1998 Scientific American article “Everyday Exposure to Toxic Pollutants” (Sci Am. 1998 Feb;278(2):86-91. Everyday exposure to toxic pollutants. Ott WR, Roberts JW. PDF: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/13757391_Everyday_Exposure_to_Toxic_Pollutants ) That paper discusses some of the initial efforts to track what pollutants people in the United States and Canada are exposed to using similar personal sampling devices. That data was lacking even in those developed countries at the time and showed many surprises. Sampling devices at this scale and cost are a great idea! Really interesting from Ott and Robert’s paper, for instance, is the exposures a crawling infant would be exposed to on normal carpets. Data at less than 1 meter height – how novel, yet how much more resolution devices like these have than the comments “of course cooking with that is bad…” analysis.

Additionally, getting these devices into the communities that are being studied is very important to avoid “developed countries solving/telling other populations what to do”-syndrome. A great TEDx talk “How to reduce poverty? Fix homes.” (Paul Pholeros, TEDxSydney, May 2013 https://www.ted.com/talks/paul_pholeros_how_to_reduce_poverty_fix_homes ) gives a nice feel for truly impactful work. As he mentions in the work Housing for Health does, “we argue strongly that the people living in the house are simply not the problem… the people living in the house are actually a major part of the solution.” Locally trained teams are the best to solve and discover the local problems. Data for intelligent design is critical for these teams. In the two major cases Pholeros discusses, after initial studying 9 targets (in the first case) and 2 targets (in the second case) were determined. Both times more work than originally planned or wanted.

Great work and I hope it leads to good solutions > that we all can learn from in the future!