I know it is a common stereotype for an old guy to complain about how good the kids have it today. I, however, will take a little different approach: We have it so much better today when it comes to access to information than we did even a few decades ago. Imagine if I asked you the following questions:

- Where can you have a custom Peltier device built?

- What is the safest chemical to use when etching glass?

- What does an LM1812 IC do?

- Who sells AWG 12 wire with Teflon insulation?

You could probably answer all of these trivially with a quick query on your favorite search engine. But it hasn’t always been that way. In the old days, we had to make friends with three key people: the reference librarian, the vendor representative, and the old guy who seemed to know everything. In roughly that order.

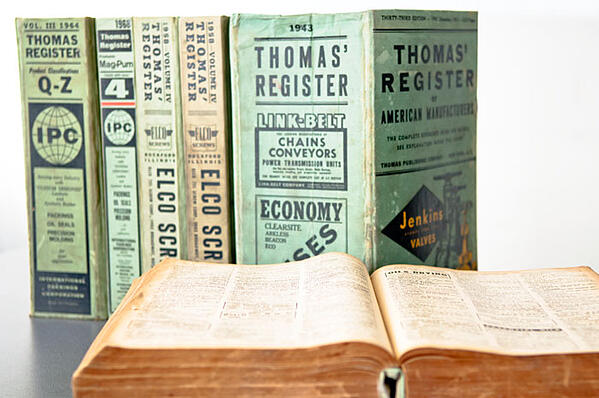

Thomas’ Register

Back in the day, any good library had a tremendous set of green books known as the Thomas’ Register. These sort of still exist, but as a specialized search engine called ThomasNet. The books date back to 1898, but in the 1970s and 1980s, they contained 34 huge volumes. They were essentially a Yellow Pages for industry. If you wanted to know who sold fiber washers, there was a list in the register. Epoxy sealing compounds? Check the big green books.

What always struck me when browsing through the Register is that someone woke up one morning and thought, “I should start a business selling plastic pipe caps.” You can only assume there was some logical progression that led to that decision, but you have to wonder.

Kudos, though, to Thomas for being nimble enough to move to digital even though the company is over a century old.

The Chemical Formulary

The Register was good if you wanted to buy something, but what if you wanted to make something chemically? Then you went looking for The Chemical Formulary, a set of 10 or 11 books that are still available in some form.

For example, suppose you wanted to start building electrolytic capacitors. In the 1940s, those were condensers, and the Formulary shows several compounds along with British patent numbers. Some of the recipes were quite specific. Some, like this electrolyte one, is very brief:

Liquid Dielectric

British Patent 493,961

Chlorinated Diphenyl (60% chlorine) 2 lb.

Trichlorobenzol 2 lb.

Tetrachlorobenzol 1 lb.

There’s no discussion about what the properties of the compound would be or why you’d use it over the other included recipe which called for ethylene glycol, boric acid, and ammonia. Don’t expect a material safety data sheet, either.

Yet some of the formulae are more specific. A rectifier element calls out specific instructions for oxidizing copper plates. Some of the entries aren’t even really compounds. One entry is about detecting forged documents using a few chemicals, but it wasn’t exactly clear how it would indicate a forgery. It is funny how the entries range from highly technical (zinc etching and light-sensitive emulsions) to quite pedestrian (how to remove alcohol spots from polished furniture).

[Styropyro] tested a few of the recipes for things like fireproofing and a reusable match. You can see his video experiments, below. We were suspicious of the contraceptive jelly formula and the compound you were supposed to smoke in a pipe to relieve asthma.

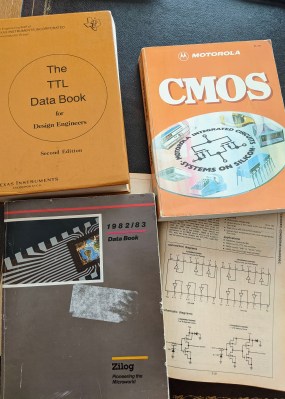

Data Books

If you wanted to find out about a particular IC in the old days, the best thing to do was to find the manufacturer’s data book. If you were in a school or a company, there might be what you wanted in the library. Otherwise, you’d have to beg or borrow a copy from the manufacturer. These were prized possessions and were rarely sent by mail because of the expense.

You’d usually get these from sales reps who wanted to sell you the parts in the book. If you got a new edition of, say, a TI databook, you might generously pass down your old copy to a junior person. It was more common to order from the company just a particular datasheet for a specific part, but that was difficult to browse through if you were just trying to get ideas without a specific part in mind. Some datasheets were works of art, with example circuits and detailed explanations about the device. There were also books for discrete components that would describe characteristics of, say, transistors, and provide cross-reference tables so you could replace one maker’s transistor with another.

You could buy some databooks at stores like Radio Shack which had, at least, some books from TI and National Semiconductor you could purchase. Catalogs were more available, and they had some information, too. However, it was rare for a catalog to have as much data as a proper datasheet or databook. There was also a trend for data to show up on microfiche. If you don’t remember that technology, it was essentially small filmstrip organized in an index card-like format. A reader could magnify the page you wanted to read on a screen.

You could buy some databooks at stores like Radio Shack which had, at least, some books from TI and National Semiconductor you could purchase. Catalogs were more available, and they had some information, too. However, it was rare for a catalog to have as much data as a proper datasheet or databook. There was also a trend for data to show up on microfiche. If you don’t remember that technology, it was essentially small filmstrip organized in an index card-like format. A reader could magnify the page you wanted to read on a screen.

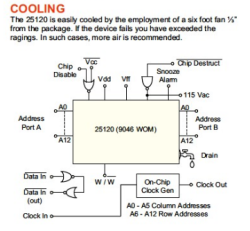

One prized datasheet was for the Signetics 25120 Write Only Memory. This fictitious device had arguably the most famous datasheet of all the spoof datasheets ever created. The schematic diagram showed a faucet as the “sink” just to give you a flavor for how silly it was. There were other spoof sheets, though, including the Zener-enhanced dark-emitting diode.

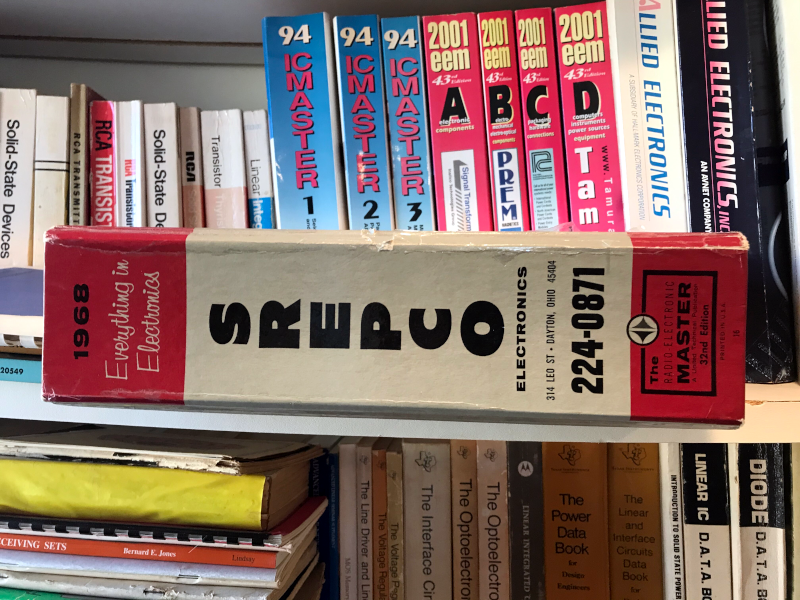

IC and EE Masters

The problem with data books is they typically covered one vendor. Sure, a TI 7474 was probably just like a National 7474, but there could be small differences. But the real problem was the many parts that only had one or two sources. If you didn’t have the right data book, you’d probably never hear of that part. That’s where the IC Master came in.

If there was ever a book that should have been in volumes, it was the IC Master. The thing was huge like an Oxford English Dictionary. It would contain just about every datasheet from every vendor at the time of its publication. These were not cheap, but they were worth it. The only problem is the vendor’s databook probably included application notes and other information that you might not get in the IC Master. But you still would at least know a part existed and could research it further.

You can find some PDFs of the giant books online. The 1979 edition takes a while to load with nearly 2,400 pages!

For everything other than ICs, there was the EE Master. This was another big book, sometimes in a few volumes, that was like the Thomas’ Register, but only for electronic components. That means it could be more detailed and if you were looking for something even vaguely electronic, this could be your first stop.

The Good Old Days?

Some people fondly remember the good old days. Not me. Give me an internet search any day of the week over poring through out of date books. Even catalogs are better since nearly all the major websites now let you search and filter through components. Many will even point out ways to save money with equivalent parts or by exploiting quantity price breaks.

While I appreciate the feel of a paper book in my hands, I don’t want to go back to those days. It makes you wonder what will be around 50 years from now, though. Will you go to the QuantumMart VR store and tell the AI what you are trying to do and let it produce a design for you? Who knows? But just as we couldn’t imagine replacing our beloved data books, it is difficult to see what will replace the tools we use today.

Photo Credit: Thanks to [Tom N3LLL] for the picture of his fine collection of reference books.

I have to say that I *do* miss the grouchy but helpful anyway old guy who knew everything (in my home town that guy ran a store out of his garage where you could buy hard to find parts (tubes, oddball connectors, strange ICs) and if you caught him on a slow and cheerful day he’d let you watch him fix your radio, or go over your design. He also didn’t report any suspicious component combinations to “the authorities” which was nice for those building variously colored boxes.

Hypothesis: internet is down for an unknown number of days/weeks worldwide. What would be the best [offline] up-to-date reference to look for part equivalence/replacement and technical reference ? I know about Turuta ebooks but is there other projects like this one ?

Offline ifixit database of disassembly and repairs would be a big win in my book also.

Surely you only need one offline – the ifixit guide to “how to repair the internet”?

This was a serious question I believe and I too be curious to know an answer to it

Unplug the router, wait 15 seconds, then plug it in again.

The answer would be….”to fix the internet…. please read the following articles online at http://www.fixtheintetnet.com..” (facepalm)

Oddly, there’s an app for that

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/feb/28/seven-people-keys-worldwide-internet-security-web

that’s interesting, the thing you need to remember is that the internet as well as smart phones are given things, so whoever is giving these, can take it back anytime :) but if you have some hard copy or some hard knowledge you can mange, so never ever put your trust in the given things…

“Offline ifixit database of disassembly and repairs would be a big win in my book also.”

I would go with an offline copy of Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Database_download

I would have bought a set of used encyclopedias if I’d had a way to get them home.

I still have a couple of single volume encyclopedias, some dictionaries (including the two volume OED with the magnifier), guides to movies and tv shows, and otger reference books.

And I still have a large number of electronic data books.

Self-sufficiency, no need to go to the library or rely on someone else.

Yes, it’s easier now to use the internet, but I want something I can fallback on.

“including the two volume OED with the magnifier”

Bought my copy, did you? :-D Yeah I hated selling it, but boy was that text small even with the magnifier.

I was helping someone move, and they put it in the garbage pile, so I brought it home. They kept the magnifier. One book club had it as an enrollment giveaway, I suspect that’s how they got it.

I keep it on a higher shelf, and the last time I checked something in it, it fell down and destroyed a keyboard.

Lately, I’ve been thinking of having a VM spooled up on a server running a windows 9x, just for all the Comptons, Encartas and other reference on CD etc I’ve got

If the internet goes down you’ll have to worry about the roving hordes of phoneless people jonesing for their twitter fix.

You don’t need the internet to shout garbage into the void do you?

Getting cyberdeck in pelican case with something like fahraday case it would be nice to cram as much knowledge in databanks as you can. Something like digital prepper toolkit…

I miss using reference libraries. Aside from the relaxing pleasant atmosphere, sometimes with seats that afforded great views, they afforded a deeper random education than the internet does.

Whilst the original visit would generally to look up something specific I would then pick a random section and grab a few rando books and look through them. The biographies section was a particularly god section.

Whereas on the internet I flit around like a butterfly spending a few seconds here and a few seconds there before watching some entertaining feline for an hour, in a reference library I would spend a couple of hours reading about one subject/person/location. And what I would read was consistent and pre-curated by the time and expense of getting it published as a book.

I wouldn’t swap back – hell no – and most of the libraries I did visit are still there. I just don’t have that initial need to go any more. So I won’t get a decent glimpse into the life of Alice B Toklas, or whatever the random finds I used to have were. I’ll just get a grin from a cat.

But there was a distinction between professional and hobbyist.

Hobbyists were centered on magazines, and some books. Many just built what was there, or variations. There was a ton of practical information, less of hard theory or calculations (until pocket calculators arrived).

We used parts that were in the magazines, a balance between some parts being used and thus available from hobby suppliers. So we knew the parts that were being used, and learned of new parts because Don Lancaster or soneone else scanned the professional literature and shook out some items.

For a long time there was overlap, we bought parts at stores that sold to repairmen. So tube companies would sell their databooks there, available to hobbyists. Obviously tube manuals, but it remained for the early solid state days. Around 1972 or 73 I bought (it was cheap) an RCA transistor databook at a store where I bought parts, it even had sample circuits like in RCA’s tube manual.

But the companies did cater to hobbyists, until they didn’t. Fifty years ago I did get an RCA hobby circuit manual (all kinds of projects), sold at parts stores, and didn’t cost much. Motorola had a line of replacement parts, “HEP”, that was in part aimed at hobbyists. I

Magazines were big, but they also provided a cheap means of publication and distribution. So there were at least five regular hobby electronic magazines in 1971, but they had spinoffs about specialties like communication. Even more interesting were the anthologies in magazine form, that were less regular, or one-offs. A single shot that collected repair articles from the main magazine. Or anthologies of construction articles. Or “101 Electronic Projects for under Ten Dollars” (one or two transistor circuits). Where did I get the money?

There were also two publishers that had a lot of books for electronic hobbyists, TAB and Sams. Deeper theory than the magazine articles.

It was a self contained world. The magazines even had Q&A columns, to ask about that teflon wire (or more iften, something that could be answered by reading the magazines).

I think just like today there is a spectrum ranging from someone building a flashy LED kit to hardcore engineers doing things in their spare time, and it has always been a bell curve. I was lucky enough to grow up with some guys who were in the latter camp and people like that are still around. There are also plenty of people who build stuff who can’t explain much of what they do or do original designs. There’s room for everyone and I think today going up the curve is easier than ever because of the availability of data as you say.

I miss the magazines. Popular Electronics was easily my favorite, but there was Elementary Electronics, Radio Electronics, N&V (still around), Circuit Cellar (still around). Look up “American Radio History” if you want to kill a few days reading old articles….

Another factor was pulling components off (FREE!!!) scrap electronics and working out what you can do with them.

Much easier now to find the datasheets, but back in the day the manufacturer reference books were gold dust.

THIS!!! I had the worst time finding any kind of electronic reference materials and certainly little to no pinout materials/ datasheets back in tha day. Now it is much easier to pull it up while everything is open and fresh and the iron is ready to strike. I would have also killed to have some sort of ee or graybeard early on in my electronic explorations to help with some shortcuts but I guess that is life. Never found one outside of a neighbor that would try and sell his broken SW stuff to me for exorbitant rates. Oh well, the hardest lessons stick best I guess.

I dunno. It’s still hard to find specific recipes with Google the way you could find them in Chemical Formulary. You get a Wikipedia entry that says “well, this could have this in it, or it could have that in it”, and nothing about proportions or minor ingredients.

There’s still old scientific american type PDFs with instructions for doing things that most people today consider super impresive even with modern gear. Tech is so much better, but a few random things seem to have been forgotten.

Iirc, you kinda knew where you wanted to go and futzed around until it worked, stuff you designed was more tolerant of errors. Dont forget the ARRL handbook and MIMS radioshack circuit series.

I kind of miss the 10 linear feet of the Motorola books, similar footage of the TI books, and the filing cabinet full of App Notes. I don’t miss the weeks it took to get them.

BTW, the faucet is for the ‘Drain”, not the ‘Sink’. In the same WOM datasheet was a photograph of the device- looked like a water tower to me!

I think the important thing missing isn’t so much the QUANTITY of information which the internet has in spades (NDAs and such notwithstanding) but the QUALITY of the information given. There’s also a middle period between the books and the internet and that was CDs and DVDs which sometimes amounted to intranets on disk. Great if you didn’t want to collapse your current bookshelf.

+1 on QUALITY! Hours spent looking at parts/devices on the internet just to find the one that includes ALL of the required / relevant specs for example (after bypassing the irrelevant adds)

Some of my Harris books made it easy to find items with particular qualities because that’s how it was indexed.

I think one thing the “good old days” had was a dedication to publicly advertised specs, available without an NDA. That way engineers could choose parts rather than managers being sold parts.

Al, you had a chance and blew it!

You missed one major difference between the old databooks and the internet – quality of content. PLEASE give me a manufacturer’s databook or catalog, as it typically had more applications information than any website thrown together by a graphics designer instead of an applications engineer. It may take looking between Signetics, TI and National’s databooks, but I would find much more detailed information on how to control and apply ( and in some cases what NOT to do ) that I could ever find on a hastily thrown together web page.

You also forgot to mention the applications handbooks. These were SOLID GOLD to any engineer, technician or hobbyist that got their hands on one. This is where the real “how to use the part” information was kept. It provided the in-depth, detailed descriptions of multiple circuits that could wow and amaze you for a given part or part family.

I still have and cherish my databook library ( I know, we just moved and I had to carry boxes of these &^%%@#$ heavy things up and down stairs ) and still reference them from time to time. Not so much the old 8051 books, but the logic, linear and transistor books do still hold real value.

I also collect the old formularies as these come in handy from time to time. Again, this is information that you can’t find on the internet as it’s deemed “too old” or “too dangerous” for people to have access to. As for the older versions, you need a cross reference to determine what the old chemical name translates to in modern times, but you can find out how to make almost anything from the old tomes.

Again, print in my book beats the internet hands down. No one can sensor a book in hand, but Google can block content at will if they feel its “inappropriate”.

Keep them away from your ditzy naturopathically inclined friends or they’re see “Oil of Vitriol” in a receipt and think it’s essential oils so super healthy.

” any website thrown together by a graphics designer instead of an applications engineer.”

I’d rather dig through FTP directories than use some of those sites. It’s either all shine and no apple, or hideous Web 2.0 crap that only looks good on the CEO’s iPad, or convoluted java based crap that gets confused and can’t find the real content half the time.

Though mentioning FTP, there was a between time, where the major chip tinkers had FTPs, or BBSs even, full of text docs.

In the early 80’s I took a course on the theory and design of digital circuits at the university I was attending and one of the required textbooks was the Texas instruments Data book. It was one of the cheaper text books I had to buy.

Thinking that everything can be found online by now is an illusion.

There are lots of datasheets and books that haven’t been digitized by now.

Neither medium can fully replace the other.

Be grateful and just use them both in harmony. Amen. :)

“Thinking that everything can be found online by now is an illusion.”

Well mainly $$$. It’s amazing what some of my old books go for now.

I regret selling my RCA Tube book for $0.25 at a ham fest a couple decades ago…

Well, I’ve got indeed some old books and magazines that predate the ISBN age. ;)

Some of these are radio magazines from the 1930s-40s that I haven’t found online yet.

Also, some books from the former Eastern Germany (GDR aka DDR)..

They are listed on eBay sometimes, but they haven’t been scanned/published online yet.

Not even some camparison types for some popular East German or soviet parts are listed online.

Except maybe burried in the Cyrillic part of the net. Lucky them who still has an old semiconductor/tube book at home that covers those exots.

Heck, there are even certain ancient words that Google shows no single (!) result for! :D

(ex. Well-en-sum-mer, remove the minuses, it means “wave buzzer” in German. That was an ancient HF device, some sort of RF generator).

Technically before Google, there was Altavista and Ask Jeeves… and websites used to exist in rings, with a central site keeping tabs on all the sites covering similar topics.

Hotbot, infoseek, lycos, dogpile…. and yahoo used to be a hierarchically organised curated index. Then before that there was Archie and WAIS and it was easier to do a gopher search than WWW search up to about late ’95ish.

There’s a part 2 but youtube won’t let me look at it unless it’s embedded:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NWs9dpCH9no

Don’t forget USENET had “Conan the Librarian”

I don’t know him, but when I first got access to sci.electronics (before it was divided) in late 1994, via a BBS, I know people like me would go to our books and look things up, depending on ease and whether the poster seemed worthy.

Lot of effort posting pinouts, and way more eftort to draw a schematic in ascii.

Someone kept a big file of common IC pinouts.

In 1995 it was a few years of commercial ISPs and I think most people knew about the internet, but it was still more like the old days. Usenet strong, and what files there were, kept on ftp servers that were part of some existing business or educational system. I remember mailing someone an IC, something I never did again because while the IC I pulled off a scrap board, postage was a few dollars.

Someone posted about a local hamfest, but “see website for details”. Except, all I had was usenet, at that point I think not an exception, so I couldn’t check the website.

Peter Deutsch helped bring the Internet to Montreal, and was involved in the development of Archie. (McGill had a gopher server for things like classifiee ads until at least 2000). He helped bring Inet 96 to Montreal. One time in 1999 someone from out of town posted to the local newsgroup, wanted the cross street for a certain address. And Peter Deutsch posted a reply. It’s not the same Peter Deutsch mentioned in “Hackers”.

sci.electronics was one of my favorite USENET groups back then.

Did you post to it?

I’m pretty sure I did. At a BBS, I had limited time, and traffic was heavy. And then in 1996 Mark Zenier organized the great division. And some of those subgroups only really saw traffic because people posted in the wrong place.

My pre-internet go-tos were the Maplin and RS catalogues, Bernard Babani books, and the slim selection of out of date repair stuff at the local library. Even since internet and google I’ve acquired some chemistry and physical handbooks with useful data in, and a TTL handbook from TI that is still sometimes more illuminating.

A particular problem searching online is when the artificial stupidity tries to be overhelpful and instead of searching for the specific property or specification you ask for, searches for the words properties or specifications of X which are 95% likely to be shortlists of a few key properties or specs and do not include the refractive index or whatever exactly you were looking for. That’s where the dead tree tomes come in useful. Damn I miss the full whack of search operators, and the dig down options to filter results, I also miss the lack of “help”, yes I am aware that that word has synonyms, no they don’t mean the same thing in the context of my search, why the hell are you polluting my results with all that trash??

Remembering desktop programs like Copernic Agent. Long since discontinued (1,000 search engines indeed).

https://www.unitedaddins.com/product/copernic-agent-professional/

I never saw much use in those. The search engines were changing every 2-3 months until early 2000s, then slowed down to 6 months or so, now maybe bi-annual. Anyway, with change like that in the latter half of the 90s any desktop app was going to be out of date as soon as published.

Yep, search engines were optimized for the masses, and the results are no longer ordered by best match, but by popularity. So often, you need to be more specific to try to exclude almost ridiculous/forced misinterpretations by the search engine, which you had not to do in the past.

This makes it much harder, because it requires you to know more terms, and possibly more exotic ones, to narrow it down and exclude irrelevant information.

Sometimes it’s really hopeless (not so much for technical topics), when there are trends that overshadow everything, and even if you know the webpage exists, you wont find it.

That’s one of the nice thing about sites like HaD. You can get some good links out of it.

I still have one of my reference books, ‘Towers International Transistor Selector’ from 1980 – my then girlfriend used to get annoyed with me when I asked her if she’d seen my tits..

Also, the then bible – Horowitz and Hill, the art of electronics – a good reference with many examples.

To be fair, there are still reference librarians, and you can still refer to them. And they’re still good at their jobs.

For me the biggest difference between the catalogs and data of yore and the online databases of today is that in many ways the old paper books were easier to _use_

The other day I spent more than an hour on the TE website looking for a specific connector that I had used many times before _but I didn’t know specifically what it was called_ .

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not a Luddite, and I love having a billion parts at my fingertips, but you run into stupid walls if you don’t know the specific keywords the other side used to build their database. Like is that .1uF decoupling cap under “ceramic” or “MLCC”

In the old paper databooks and catalogs, if you had some clue what you were looking for, you could leaf through them quickly, dive into a family, and sort yourself out by drawing/picture/block diagram in fairly short order.

In the modern world you find yourself on a website trying to back engineer the thought process of the person who had the job of putting everything into categories and creating all the links.

“Now, did they call this “shrouded” or “boxed”… or maybe “rectangular board connector” ?? Or is the “rectangular board connector” the thing that plugs _into_ the part I’m thinking about.

What you mention is a very valid observation, and it’s not related to digital vs analog only.

It’s the same as going to a library, where you have to say which book you want to lend, instead of walking the aisles, and just exploring what is there, and finding something valuable or interesting.

When you are searching without exact knowledge (which is often the case), having to specify things logically is often not as effective.

There are ideas to improve search engines, finding things by similarity (drawings) and other types of similarity searches, but they are not really mainstream. And it’s just more fun, to explore directly, than getting filtered information by a search form/clerk.

Taking in information directly, is like making experiences yourself: you get information and insight a tightly guided experience/search cannot provide.

I was particularly taken with the phrase: ” and the old guy who seemed to know everything. ” And yes, I have known some of those, like you and Tom!

I have a bunch of old databooks from the ’90s that I accumulated from thrift stores, almost everything I encountered. The most memorable one to me was an Intel book about the 8088 that called it an 8-bit CPU and compared it with the Z-80 and 6809. But of course the TI orange book for TTL was always the most useful. I also found two sets of the Compact OED back then, one of which still had its box and magnifier.

The early ’00s was a transition period when I would download PDFs, then print out the pages I was using. By 2005 or so I had gotten used to just keeping the PDF open in a window. In fact, right now I have a TI TTL data book open in Preview.app, among others. Now when I download a data sheet, I’ll drop it into a big folder full of them, and let Spotlight sort them out. From time to time I will still print out a pinouts page if I need to scribble on it.

I saved so much in my early days of Usenet, and then full internet. Some of it wasn’t permanent, but it all felt impermanent, maybe I feared losing internet access. Or maybe because it was”new” (I’m talking 1995), and yiu can’t trust new.

But it’s just jumbles of files on old hard drives now, to find the really valuable stuff, wouod take too much wading.

I miss the smell of my 1980 TI TTL data book. Web pages just can’t capture that combination of musty paper and solder fumes.

While the Signetics 25120 was indeed a nonsense joke datasheet we all have seen, the engineers at Signetics did “make” a few hundred real 25120NFG samples and gave them out to people “in the know”. The chips themselves were either die-less DIP dummys or unmarked rejects of some sort, but were officially marked in the Signetics font. I just sold mine, and I suspect it is ending up at the Computer History Museum.

Also, before the IC Master and EE Master was the Radio Master. These date back to 1934 or so. They are fantastic references that get overlooked by many old radio collectors and restorers.

I remember in 1983, my freshman year in college, creating a “fake” company name so I could request free copies of TTI databooks. Then in the mid 1990’s convincing my boss to spend the money on a set of IC Masters to help me with bench repairs. The most valuable section was the manufacturer’s logo decoder…for id’ing repair parts. If my RCA op amp data book with its xreference by part number was my Bible, then my Haftorah had to be the Crydom Thyristor Data book

I still have…all boxed up….just in case

“I still have…all boxed up….just in case”

In other words, you have them all encased, just in case.

B^)

I spent a few years working in a library and I worked the ref desk daily. It was an absolute nightmare. I spent most of my time looking for books for lazy people because our funding was based on the amount of ‘service’ we provided. Every patron we helped got a check on a master list. If we showed people how to look up information for themselves we didn’t get to make that little check mark and our budget suffered. I was actually told not to direct patrons to the catalog. Also, our catalog was web-based so no internet meant no access to the catalog. It didn’t really matter as most patrons only wanted to buy bus passes, check out the latest drivel from Bill O’reilly or use a public computer to apply for benefits. But we had a coloring club and a teen room full of manga and several 3D printers and other tech toys that no one had an interest in learning about. It was absolutely soul crushing.

That’s so depressing! I always imagined reference librarians as the people who would help you get started on your hunt for a shipwreck, or some obscure fact for a newspaper column pop history, or something cool like that.

I even thought it would be cool to invite all the librarians in a city to a youtube reality show where you just pick a completely random question, and interview everyone about the cool stuff they found on the way…. But it’s mostly just watching printers gather dust?

Sounds amazing. Very few people go onto adventures in general, I suppose that’s why such novels and movies are inspiring. Then again, there are many documentaries (i.e., real events) that start exactly that way, especially archeology.

Would be worthwhile if we lived this magical life a bit more. That’s what friends are for, friends of any age, to explore the world exactly this way. I think that’s the ideal of a scientist and explorer I always had.

But uni is very disappointing in this regard, too. Making amazing discoveries, vs. writing a bureaucratic paper and focusing on formalities, with research on an absolute detail.

Not “romantic” at all either. We have to get out of this seriousness in a way, because life is not meant to be wasted living as a machine. It would be rather fascinating, if we could relegate this boring work to machines, and take the effort to formalize it enough so it can be coded in software. Maybe then research could be more fun again.

Another great datasheet I have still got a copy of is the PSI (Parody Standard Specification: Gnome Series) PS GN1 1982 specification for ‘Precast concrete gnomes’ which has sections for ‘Gnominal size, Greying streakage test (which requires mounting the gnome on a roundabout) , Wooly cap (three bears on edge) test and Tolerance for gnomes (the tolerances are listed in section 5, Fable one).

I was in the between times of the physical Books and the Net. My mother got me the TI IC Databook for Christmas and some times I would venture to the used Book Store that had a Electronics section. I used Newsgroups and Yahoo GeoCities sites for crudely made datasheets and schematics people made in ASCII. I didn’t see any Electronics Magazines in the stores, if they did cover Electronics it was more about Computers then anything. I gave up on Electronics at one point and just worked on Computers. Back in 2012 I got back into Electronics. Thanks to YouTube, HackaDay, Sparkfun and the eevblog I was able to learn quickly.

So, is there no one pointing out the serious error about electrolytes VS dielectrics?

The recipe shown is a dielectric.It does not conduct. It is meant to be the best isolator there was (and it was, but PCBs and the other substances are horrifically toxic).

The electrolyte based on borax and glycol is meant to conduct electricity as well as possible.

The former is for non-electrolytic capacitors and for transformer isolation and such. The latter is for electrolytic capacitors that use an extremely thin layer of aluminium oxide as a dielectric.

That said, for the average hobbyist, datasheets were not all that important. You’d have a little transistor or tube reference book with pinouts and a few basic specs and that’s it. Perhaps a copy of a copy of a few sheets of info about TTL and opamp ICs, and that’s it. All you needed for the stuff people built in the pre-microcontroller age.

I started fiddling with electronics around 2002. Information was starting to be available easily by then. But some older stuff wasn’t digitized yet, so when i was looking around for tube info, someone mailed me some copies of tube info physically.

Most people would be building stuff with universal components. Need a power transistor for a PSU? You’d rip one out of the PSU of an old TV or something. Need a high voltage switching transistor? Take one out of the flyback circuit. Perhaps you wouldn’t know the exact specs, but it would be roughly suitable.

Many designs from the late 60s and early 70s, perhaps 80s, used the famous ‘TUN’ or ‘TUP’ transistors. That translates to ‘Transistor, universal, NPN/PNP’. So that means any basic small signal transistor you can get your hands on, like the bc107 or bc547.

Things are of course different for the professional, but for the hobbyist, it was more about what you had, than what was the most perfect match for your needs.

Having an “old” guy, or really just someone with more experience than you, of any age, is still very valuable. Learning on your own and making every possible mistake can take a lot of time. A little guidance/blue print initially can help you find workable solutions, and then explore from there. Starting from nothing and having every option presented is overwhelming.

Wikipedia is a great example, often complete, overly complete even, compared to what you study in college as well, but most of the time useless to learn anything new. You just need to have the relevant information simplified and cut down to what you need to actually get to a concept fast enough.

Forums are similar, knowledgebale people often just dump their “wisdom” without much filter or adaptation onto you, and hope you learn something from it or secretly wish you go through the same pain, before you are “worthy” of mastering the subject.

It’s hard to find a middle ground between overly simplified, so you can’t use the knowledge much outside it’s given confines, or overly complex, so there is so much to go through and sort and verify and understand, you have little hope to progress, due to all the other topics you need to explore as well.

Having a good teacher is still very useful today, especially in analog electronics.

Wikipedia, yah, there’s a whole topic. 10 years ago it started getting so tech subjects were not explained from high school level, more like 2nd year degree, and now it’s got worse, post grad level on some stuff. Contributing to this is that there’s been a lot of “lumper” campaigns where a small technology or subpart of a large one had it’s own page 4 or 5 paragraphs worth, detailing it well, then the article got “lumped” into an already large article on the topic, and may have retained 2 paragraphs worth…. until someone else came along and thought THAT article was too verbose and cut it down to 2 lines. Continual fight between the expanders and explainers and the people who want to condense everything. In extreme cases you can find you enter a topic and the topic heading redirects to another article from which all trace and mention of the topic you entered from has been removed.

However, some strategies help… first, right to the left of the search box there is the view history link, you can use this to dig back to previous revisions of the article, take care as there may be inaccuracies, but sometimes you can find your way back to a version that was in much clearer layman language. Also you may retrieve chunks of info from when another topic was pasted into it, before those several paragraphs got reduced to 2 lines or removed entirely. Secondly, there is a simple English version of Wikipedia, and some articles in that are much better at explaining things from a basic level. However some articles are either entirely absent or thinking simple means short, there is an even more dense and impenetrable version of the higher tech ones. Potentially of some help in some topic areas are Wikibooks, which offer a more gradual slope of introduction to various subjects. 3rdly, should you find the info you require was folded into another article then deleted, and it’s an extremely frequently edited article, such that finding the one version that persisted for maybe an hour 5 years ago with ALL the info in it is a huge problem, you can find sites that archive deleted Wikipedia pages, and hence find the article that got merged that way. Sometimes but not always you can find the info from the stub page in the view history.

You may find also that some of the references cited are actually easier reading than the article. If they are dead links, use archive.org to pull them up. In fact archive.org can be a good resource also as you may find older books on the topic that give you an easier “in”.

Forum knowledge is another hard thing to extract, particularly on things that don’t get documented very often. The regulars have been keeping up to date for years on various changes and things said so they’ve got a mental model of “everything” but what you need to know is spread out piecemeal over years, things that changed, things that didn’t. Threads that were bumped side by side for a period of months, then one got pinned and the other hasn’t been posted on for 2 years so is lost in the depths, but actually formed part of the mindset or zeitgeist kinda thing of the pinned thread. Then when they say “it was discussed on the forum” yeah, good luck, you might have to follow the same months long rabbit trails everyone else went down until the actual real answer was known, maybe the thread titles actually have nothing to do with the conclusion. So, sometimes you can sort the forum by date of first post and go back to when topic first appeared and manage to make some sense out of it. Sometimes you can just pick at it with google using the site: operator and timeframe tools if necessary to do a directed dig for the nugget you need.

I probably have well over a hundred reference books filling a bookcase and several filing cabinet drawers. The ones I used the most were four volumes of the Markus Sourcebook of Electronic Circuits, first published in 1968. Thousands of circuits that I used as inspiration. All of this will probably be recycled or land fill when I change phase. At the age of 80, I only have another good 20 years before these will be declared obsolete by someone who doesn’t care. Not sure that the local Maker groups would even like them.

Well the important thing is it’s digitized and available ($5.44 used).

I have here both the TI data book shown, and later one. Oh and differences between a TI SN7474, and a NSC DM7474, is in the mask used. They still are the same functions, and still have the same cock-eyed pin outs.

Google still can’t tell me where to buy self-sealing stem bolts.

You just can’t get the duranium. The last one known to sell was seen at auction slightly north of $2k. Though are you building a reverse-ratcheting routing planer for a museum or something? Inverse phase locking routing planers are where it’s at now.

has anyone else noticed the decline in search engine relevance and just overall ease of finding info on the internet? My current frustration is learning the ins and outs of late 90’s chevrolet 350 engines, and their associated electronics, and the results are….dismal. all of my results from the search engines are choked to death with arm chair “experts” talking out their asses on forums, dead links, and sponsored ads that don’t help at all. Google images is even worse, don’t get me started. Hey google, if i include the word PINOUT, prolly good to show me things that are actually a damn pinout diagram, and not random bullshit photos.

But is it google, or just so much more information?

Until some point (and I’m not sure when that was), you’d get useful hits on even obscure searches. You.might get only one return, but it was relevant, and often useful.

Then eventually you’d get lots of returns for any search, but the useful was buried. There’s incredible duplication, and endless advertising. It takes effort to find.meaningfull results.

So google has to be defaulting to favor the “bad” (which they think is “good”) but everyone is generwting “content” and wanting to be first.

Just tge other day I was searching for something about an ancestor, and I found a paper I’d not seen before. But it seemed to be duplicated at other sites. Except it wasn’t, it was a lure to get me there. I can see putting false keywords about popular topics, as lures, but this is someone from 150 years ago.