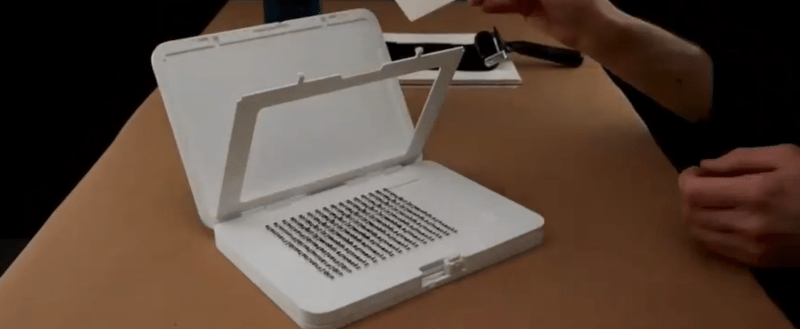

A few machines have truly changed the world, such as the wheel, steam engines, or the printing press. Maybe 3D printers will be on that list one day too. But for today, you can use your 3D printer to produce a working printing press by following plans from [Ian Mackay]. The machine, Hi-Bred, allows you to place printed blocks in a chase — that’s the technical term — run a brayer laden with ink over the type blocks and hand press a piece of paper with the platen.

The idea is more or less like a giant rubber stamp. As [Ian] points out, one way to think about it is that white pixels are 0mm high and black pixels are 3mm high. He suggests looking at old woodcuts for inspiration.

This might be just the thing for doing something fancy like custom invitations. Seems like it would be pretty hard to do a booklet or magazine, although anything is possible if you are patient. Real type was made with lead and we doubt the plastic type will be quite as durable.

Of course, if you just want the old school feel, you could try a mimeograph or hectograph. In the old days, typesetter put type in from big cases that often wind up now as shadowboxes. But then came the Linotype.

I think the internet will be the overarching world-shaking technology remembered from this era. It’s what’s made 3d printers possible.

It’s appropriate to see plans for a 3d printed printing press releases for free online. Quite the completed circle.

I won’t argue that the Internet assisted in the development of 3D printing and pretty much everything else, but what part of 3D printing do you think would have been impossible without the Internet? We had many ways to communicate before the Internet, and there was even a maker movement before the Internet, even before BBSs. For the most part we operated through print media, appropriately enough.

I think it’s more a case of enabling the technology to take off/reach critical mass in a very short amount of time. Imagine buying a monthly magazine for the CD containing a handful of stl files you can print on your home printer, or sharing designs with your friends on floppy? Now it’s more like, oh this thingamabob on your LG dishwasher broke, head on over to thingiverse and download a replacement. Now you read about some person building their own 3D printed Raman Spectrometer and you start printing parts before breakfast. Now you’re cooking with gas!

Missed by 3 btw, anniversary of first Gutenberg Bible printing was supposed to be 23rd Feb. Not sure if it was just coincidentally almost not quite nearly semi-serendipitous, or a swing and a miss. Though that was before that Gregory the Thirteenth fella messed around with the calendar, so maybe you’re 6 days early.

It’s good to see someone is doing this. I visited a print shop back in the halcyon days of 2019 that specialized in letterpress printing. Or what they CALLED letterpress. Their printing actually involved sending digital images to a company that specialized in making bas-relief polymer plates using an optical hardening process similar to what is used for rubber stamps. I wondered at the time about FDM printing plates using a filament such as TPU, but realized that it would be difficult to get anywhere near the resolution that they are getting with an optical process.

I guess similarly, you could generate silkscreen masters by fdm printing with a flexible filament onto polyester fabric. Similar to an article on HaD a while back (years ago, in December 2020) that demonstrated printing solid shapes on a mesh material like tulle (https://hackaday.com/2020/12/18/remoticon-video-how-to-3d-print-onto-fabric-with-billie-ruben/) (seriously, I thought it had been years since I saw that article) that involved printing a base layer, then laying down the fabric, then printing additional layers that adhere to the base layer through the fabric. Again, the detail-limiting factor is how thin a bead you can print.

And then, there was the time someone printed a Selectric typeball (https://hackaday.com/2020/01/26/can-you-help-3d-print-a-selectric-ball/), but I guess the less said about that one, the better.

It’s easier to just cut vinyl out on a cameo and iron it on as a mask now instead of wax Or rubber agent. Nowadays. Just saying for info. 3d printing is going farther then nesscery here is all.

Umm, there are some people out here who do “letterpress” with cases of metal type, hand composed, and then printed.

I learned from my father on a 19th century Albion which required a lot of manual labour. You set the type, put it in a chase, rolled ink over it, put a sheet of paper on the tympan, lowered that onto the type, rolled that stack under the press and pulled a large handle to apply pressure. Then you would release that, roll the bed back out, lift the paper back off and remove it.

These days I use a much smaller press which is simpler to use. It’s still a 19th century cast iron press but this one is a table top press. I roll ink onto a metal plate on the top, put the type into a chase which sits in the press and put paper opposite it. Then I can pull one handle and rollers roll down over the ink, and across the type, the paper presses up onto the type, and as I release the handle the paper moves back, then the rollers roll back (the plate the ink is on rotates slightly each time).

A lot of people have gone to photo polymer plates because they are more convenient.

If you want the type to last longer, you might try printing the type with a flexible filament. You’ll probably lose some sharpness when printing (it’ll squish around a bit), but it’ll also probably hold up better over many impressions. (The toy press I had as a kid used rubber movable type, which is what made me think of it).

Honestly I can’t see this being a problem, PLA is extremely rigid as in so rigid you can use it in a press brake.

https://youtu.be/wsxFXTKaXdI

Yea that’s my point – I suspect that using a rigid material like that isn’t going to hold up, especially since you’re printing small raised areas, which I suspect are going to get damaged after a few cycles. Using a flexible material for the type means it’ll spring back more, with less likelyhood of damage from normal use. Of course, the paper you’re printing on may provide enough cushion that it doesn’t matter for all I know.

“Real” type is usually metal or hardwood.

“Letterpress” these days seems to frequently be about getting a strong impression in the paper. In the old days people would aim for a “kiss” impression which barely indents the paper. The idea being to just transfer ink onto the paper.

The deeper the impression, the more damage you will do to the type itself.

That’s right – “letterpress” today is more of a debossing method than a way of transferring ink. Which is more just a corruption of the word than a corruption of the process. Letterpress operators still use this for transferring ink, but find that impressions in the paper are a novelty that people will pay for, since it’s not something you can get from your laser or inkjet printer – the technologies that almost eliminated letterpress printing in the first place. This fact, along with the fact that you can have plates made using any font you have on a computer rather than being limited to what is in your type cabinet is probably responsible for bringing the craft back to life.

Oh – forgot what I meant to say: the plates used to do letterpress today are polymer, and are resilient enough that even when making deep impressions in the paper, they can withstand thousands of impressions.

This will be perfect for producing my revolutionary tracts when THEY shut down the internet! I would like to make a jellygraph (hectograph) though if I could find hectographic pencils.