You don’t often turn on a light and think, “That power company is sure on the ball!” You generally only think of them when the lights go out without warning. I think the same is true of search. You don’t use Google or DuckDuckGo or any of the other search engines and think “Wow! How awesome it is to have this much information at your fingertips.” Well. Maybe a little, but it is hard to remember just how hard it was to get at information in the pre-search-engine age.

I were thinking about this the other day when I read that Ruth Freitag had died last year. Ruth had the unglamorous but very important title of reference librarian. But she wasn’t just an ordinary librarian. She worked for the Library of Congress and was famous in certain circles, counting among her admirers Isaac Asimov and Carl Sagan.

You might wonder why a reference librarian would have fans. Turns out, high-powered librarians do more than just find books on the shelves for you. They produced bibliographies. If you wanted to know about, say, Halley’s comet today, you’d just do a Google search. Even if you wanted to find physical books, there are plenty of places to search: Google Books, online bookstores, and so on. But in the 1970s your options were much more limited.

Turns out, Ruth had an interest and expertise in astronomy, but she also had a keen knowledge of science and technology in general. By assembling comprehensive annotated bibliographies she could point people like Asimov and Sagan to the books they needed just like we would use Google, today.

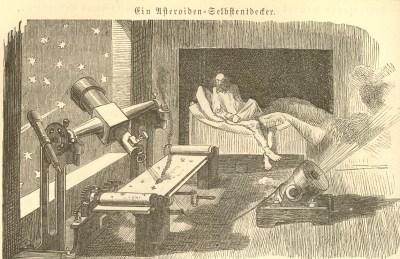

Author Mark Littman wrote Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System. The book contains an article and picture of an automatic asteroid finder from 1873, and Littman writes:

When in this book you find the names of people never fully identified anywhere else, when you find the phrasing precise, you know you have encountered the touch of Ruth S. Freitag of the Library of Congress. She has at her fingertips the most amazing information. It was she who contributed the vignette on the automatic asteroid finder. Her encyclopedic knowledge and unfailing good spirits make me very fortunate indeed to have her as a friend and mentor.

She was fluent in several languages, including German and Italian. She even contributed to the computer-age with her work with computer programmer Henriette Avram on MARC, an electronic library format. She didn’t just bibliograph astronomy, either. The Battle of the Centuries, for example, covers debates on when a century starts and ends. So was the 20th century 1900-1999? Or 1901-2000? You can see a bit of Ruth’s personality in the bibliography which starts with a song from a 1900 issue of Punch called Song for the Year 1900.

Ruth was known for helping Carl Sagan while writing Comet and dined with the likes of Isaac Asimov. She was an unusual woman for her time — spending 1945 to 1947 in China as part of the Army and working in London and Hong Kong at the American Embassy for six years. She graduated with a master’s in library science in 1959 and was recruited by the Library of Congress, where she remained until she retired in 2006.

As a young engineer, I remember seeking out the older engineers at work for advice. Now, nine times out of ten, people will turn to the Internet instead. I wonder if Ruth felt the loss of that the same way we do?

pssttt… Asimov’s first name is Isaac and not Issac. You might want to give Google a try some time.

Actually i have that feeling every time a search result comes up. How lucky to be living now. New old device on my workbench: just download the docs and start repairing. So strange that educational institutions still ignore the power of this. I still wait for the first exam to allow looking things up…

Ps. Should’nt it be Isaac?

Emphatically YES, IT SHOULD! But… it shouldn’t be “should’nt”.

> You don’t often turn on a light and think, “That power company is sure on the ball!”

Us Texans are pleasantly surprised when our power works.

Personally I find a lot of more “antique” search and indexing methods as interesting.

Be it the fancy way to sort cards by poking a pin through a set of holes on the side, some have a cut out, and others don’t. The ones that have the cut out will fall away and the rest follow the pin. And one can use multiple pins to sort by multiple things. An interesting solution to be fair.

Similar things can be said about indexing solutions for books and larger collections as a whole. Or various tricks for making calculations more easy by hand, etc. And a fair bit is somewhat applicable to modern computer architecture design to be fair.

At times I am honestly surprised it took until the 1940’s before computers turned up on the world stage. That relay computers didn’t catch on earlier is fascinating to be fair, the technology existed in the late 1800’s to make it a reality, yet it didn’t despite some fields having potential benefits from it. I guess mechanical tabulating machines just help a competitive edge at the time, but to be fair, these were to a large degree computers of their day, all though not programmable ones able to execute any arbitrary code like the ones we have today.

Could just be the good old “why would you need such wasteful features?!” hindering progress at the time. (aka, “don’t fix what isn’t broken!” An attitude that at times stifles innovation. But a lot of times one do have to focus on where efforts actually are needed, instead of fixing what needs fixing the least.)

I suspect that technology didn’t exist actually. Of course tubes were available but, were there reliable enough to achieve reasonable MTBF beyond nice looking PoC? Also, the underlying theory (A.Turing) wasn’t advanced enough to make the designs robust enough to solve real world problems.

The vacuum tube might indeed not have been up to snuff.

But relays for telecoms (telegraphs) were in use in the late 1800’s, and there the reliability weren’t terrible.

Speed and power efficiency might though be lacking, but so were it for the computers of the 1940’s. (of which a few were relay based.)

And considering how relay based computers survived into the 60’s, then it is honestly a bit interesting how people didn’t at least do more basic stuff earlier.

After all, the turing architecture isn’t the first computer architecture.

Though, a basic general purpose architecture is actually fairly simple, and can fairly easily be implemented with paper tape or punch cards. And if one only makes it jump forward on IF statements and use a simple counter for how far it should jump. Then even with fairly simple load store instructions and only a couple of basic registers one could do fairly advanced programs. And for more advanced stuff, just make the paper tape into a loop. (or maybe use something stronger than paper for the common programs.)

I have been looking a bit at building a simple relay computer myself sometime.

The relays, however, are terribly slow. I haven’t studied history of their development but I expect those from ’50-’60 be smaller and faster (and more reliable too) than their older brothers. In general WWII brought huge advances in technology and mass production (quality control). And to build a computer and make it a product you need a lot of parts especially if they are discreet. I mean we could build a computer before WWI but it would be so prohibitively expensive (including operation cost), that literally no one could afford it. Without reliable technology such computers might be even slower than humans if you factor in repair time. I believe, we didn’t miss opportunity to build computers earlier.

Reliability didn’t seem terrible to be fair. Nor cost.

Considering how the 1890 census in the US were greatly accelerated by electromechanical tabulating machines. Greatly reducing the needed processing time from the prior 1880 census that took 8 years to complete.

And in the 1910’s, electromechanical tabulating machines were seen as a fairly central part of any larger business’ accounting department. And manufacturers such as IBM were already on center stage at this point.

And it isn’t a large stride from electromechanical tabulating machines to that of computers. And I am surprised that this didn’t happen. I suspect the main reason is that the functionality of doing more state base control and jumping forth in an automated program were seen as unnecessary features when one could just employ a comparatively cheap human to do it at sufficient speed.

Not to mention that a human could just look through a text book and also use a note book to do far more complicated tasks by braking a process into smaller tasks that the simple machine in turn could accelerate. Considering how this were the case long into the 70’s.

But during WWII, intelligence gathering operations couldn’t just employ more people, spies were an issue there. Not to mention that full automation had some minor speed advantages too. So that it hit home here weren’t surprising in my regard.

And one can actually build a fairly decent relay computer with only a few hundred relays. This is however a few more than the tabulating machine used in the 1930 US census that only had 50 three contact relays, a bunch of electromechanical counters, among some other stuff.

That is exactly my point. The technology didn’t scale. It was enough to do counting but not for running 5-10 (?) times bigger machine with a lot more complex circuitry and without enough number of properly educated technicians. It was definitely feasible bot not profitable.

During WWII governments employed highly skilled people to develop various (not only computer) technologies. These were investment necessary to push the progress, to finish the research and build some more prototypes. For one reason (shorter planning) or another (The Great Depression) private sector didn’t do it earlier.

https://hackaday.com/2019/06/18/before-computers-notched-card-databases/

Thanks for the link to the article I referred to. Now people can bask in the glory of these cards.

Tried finding it myself, but luck weren’t on my side…

“Ein Asteroiden – Selbstentdecker”

Where did you get that image? I can’t find it with DDG.

https://www.graphikportal.org/document/gpo00240206

Here is the page with the rest of the description of the machine. If anyone is interested, I can translate it into english.

https://www.graphikportal.org/document/gpo00240202/F21B1626

You should mention that this is a caricature.

I think that much is obvious, the cannon kinda gives it away ;) But it’s nonetheless interesting how they thought to solve the problem, even if at the time it was meant as a joke. In principle the method is to detect light where you didn’t expect a star or planet.

Makes me wonder what the difference between a human bibliographer and a computerized algorithm in the information they help retrieve? How to you put the “Human Element” into an algorithm versus how do you put the raw computational power of a computer into a human?

We don’t really ignore people like Ruth, we barely have the time for Sagan and Asimov.

I couldn’t find the podcast I listened to in which James “The Amazing” Randi talked about Asimov. He related that Asimov had modified an IBM Selectric to use pin fed paper and could type a book on one subject while talking with you about another and answer a phone call.

As I was looking for the podcast I came across a note I sent to a local librarian who had an extensive personal site.

The world is full of amazing people. I’m glad that I come across many of them.

I found the to the Randi on Asimov podcast, worth the listen.

http://itricks.com/randishow/wp-content/uploads/Randi100107.mp3

Hooray for featuring Freitag. So, how about an article on Vannevar Bush now?

Interesting information about Asimov – well, they did say that “…behind every great man, there’s a great woman” at one time, although that’s probably politically incorrect these days.

This brought to mind this film (from a play), that my mom and I watched and liked. My mother had a job at a large law firm with a substantial library and knowing how to use it to help the lawyers was a significant part of her job.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desk_Set

Thought it might have been loosely based upon Freitag but the years aren’t quite right. The play was actually based upon a librarian at CBS.

There is no need to possess encyclopedic knowledge anymore, when “you can just Google it”. Or is there? if you command a lot of facts, you can potentially correlate them quickly, possibly leading to new ideas.

Perhaps as an indicator of our collective loss, searching GOOGLE for “Song for the Year 1900, Punch” or it’s varietals provides little value

To pharaphase: There are many things on heaven and earth that fit not into your schemes Google

Use quotation marks: “Song for the Year 1900” Punch

Second result, after this Hack-a-day post: https://www.loc.gov/rr/scitech/battle.html#song

Ah! Terrific! This is the precise bibliography, compiled by Freitag and regarding century boundaries, that the article mentioned.

“You generally only think of them when the lights go out without warning”

It is like being a plumber: if you do your job right nobody notice but once you make mistake everything is full of sh.. sevage.

What Google fails to do today was the strength of Ms Freitag – the ability to pull together relevant but thinly pertaining threads. Similarly she could truly interpret whereas Google is disconnectedly thick… Long live human beings 😉

A lot of stuff isn’t online, it coming before the internet. Even when it is online, like all those hobby electronic magazines, it doesn’t show up at google.

Lots of old material is still relevant, when something is new there’s a lot more detail than later. Yet often it’s not referenced, because it’s not a webpage. “Curated lists” would help a lot.

I drop in references to old magazines in the comments here because sometimes an article is still the best source on the topic. I may not always remember dates, but I can remember the articles, and the general sense of the date.

If a librarian has to find articles for someone, it makes sense to keep the list. And in doing those searches, they may come across unrelated things that stick in their mind for some other search.

Kids today aren’t getting an overview.

I ran into an absolutely amazing reference librarian one summer when I was an undergrad physics intern at the corporate research lab of a mid-sized instrumentation company (Gould). I was on a mass driver kick back then (Gerard K. O’Neill was publishing about building settlements at L-5, for which mass drivers would be a big benefit), so I asked her for anything she could find on the subject. She asked if it was work related, I said “no”, and she said “come back in a week.” She had three bankers’ boxes of material for me. Wonderful lady!

Oh – this was in 1976. By the way, I’d met Isaac Asimov the summer before, at a World Science Fiction Convention :-)

As with all technologies, Google enriches the lazy while impoverishing the capable. It’s leveled the playing field by moving power to those least equipped to apply it well.