Our Hackaday team is spread across the world, but remains in easy contact through the magic of the Internet. A number of us hold amateur radio callsigns, so could with a bit of effort and expenditure do the same over the airwaves. A hundred years ago this would have seemed barely conceivable as amateurs were restricted to the then-considered-unusable HF frequencies.

Thus it was that in December 1921 a group of American radio amateurs gathered in a field in Greenwich Connecticut in an attempt to span the Atlantic. Their 1.3 MHz transmitter using the callsign 1BCG seems quaintly low-frequency a hundred years later, but their achievement of securing reception in Ardrossan, Scotland, proved that intercontinental communication on higher frequencies was a practical proposition. A century later a group from the Antique Wireless Association are bringing a replica transmitter to life to recreate the event.

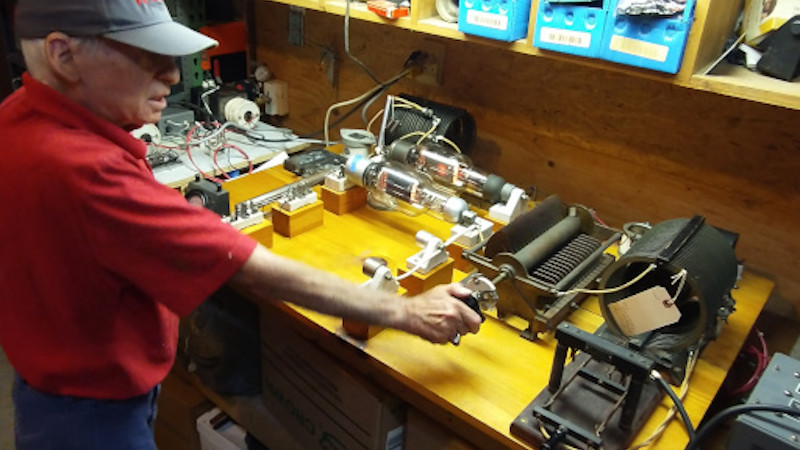

A free-running oscillator is today rarely seen in a radio transmitter, but at the time their single-tube Colpitts oscillator using a UV-204 transmitting tube would have been considered a stable source. That fed a 1KW power amplifier using three more UV-204s in parallel, which in turn fed a Marconi-style T antenna design with an earth counterpoise of multiple radial wires. The replica was originally built for an event in 1996, and substitutes the similar 204A tube for the now unobtainable UV-204. Even then, hundred-year-old tubes are hard to find in 2021, so they could only muster a single working example for the PA.

All in all it’s a very interesting project, and one of which we hope we’ll hear more as the anniversary approaches. If we can get the transmission details we’ll share them with you, and let’s see whether the same distances can be traversed with the more noisy conditions here in 2021.

To demonstrate how advanced this transmitter was for 1921, take a look at the Alexanderson alternator, its mechanical contemporary.

Damn, that’s some proper power from a free running oscillator.

I hope they span the Atlantic with it!

Don’t forget, Howard Armstrong was involved with 1BCG, helping to build the transmitter, at least. Though apparently not involved in the receiver building, other than inventi g the regen and superhet receivers.

I remember the 50th anniversary, I actually experienced it when the Dec 1971 issue of QST arrived, an article about it.

In 1921, it was really big news. Apparent!y they ran out of exclamation marks.

It was 20 years after Marconi spanned the Atlantic, and 40 years before OSCAR 1 went up, three events all happening in December.

On a technical note, Paul Godfrey’s superhet receiver used an untuned IF strip. No IF transformers, very little selectivity. We think of superhets as providing selectivity, but the initial goal was to get amplification, and that was easier at a lower, and fixed, frequency. Good selectivity only emerged in the mid-thirties. Now you can so easily get gain without tuned circuits, selectivity is well defined and separate.

I’ve never seen the schematic of Armstrong’s original superhet receiver.

Nowadays, it’s a wonder one can span the Atlantic at all with all the

RFI created by our modern electronics.

Power is out in almost all of Louisiana due to Hurricane Ida.

It would be interesting to hear what the noise floor is on HF there.

I know that whenever the power goes out where i am, the noise floor on

my portable drops to near zero. So was this an actual recreation or did

they tune the antenna to achieve the lowest SWR? Did they even know about

SWR back then? Makes me wish I could go back in time to see it happen.

In 1921, radio was still very early as a practical thing. Even if SWR was a thing, hams wouldn’t be fussing about it.

SWR really became a thing when coax came along, so after WWII

They just tuned for maximum antenna current

All technology was once new technology……

The fist documented ship-to-shore voice (and music) transmission took place from the yacht Thelma at a regatta on Lake Eire in the US in 1907. Check out the schematic of the transmitter. That has to be THE definition of “hot microphone!”

https://earlyradiohistory.us/1907df.htm

Forgot to add the information specific to Thelma:

https://nmgl.org/first-ship-to-shore-communication-summer-1963/

Lake Erie.

Also, in your 1st link, labels for images under TX and RX are reversed. TX has microphone in the antenna circuit, not receiver. RX has “telephone” and audion, not transmitter.

So is someone over in Europe going to try to receive the signal with 1920 equipment?

In 1921, there were some initial tests, no success. So they sent an American over, “Paragon” Paul Godley, with both a regen and a superhet receivers. He set up first in London, I think it was, and too much noise, so he moved to Scotland.

The test took place over ten nights I think. Godley heard the official station, but others too. And one bootlegger, a callsign but the owner came forward.

News of reception was by telegraph.

A year or two later, there was successful two way communication.

An important part to this is that there was a lot of competition for a small segment of the radio spectrum. When the Titanic sunk, there were reports of interference. The Titanic showed the value of radio, so the Radio Act of 1912 was enacted in the US. It made the rukes more rigid, and sent hams to 200 metres and down, like 1.5MHz and up. These were deemed as useless. Hams had no choice but to use them. Hence the need to prove the higher frequencies were useful.

Broadcasting became a thing in 1922, and a few years later, hams went from having everything above 1.5MHz to smaller slices going up the spectrum. And slowly the slices got smaller. Though in recent decades, as other services move to VHF/UHF and satellites, some new bands have been added.

Just a few years ago, some low frequency bands were added, the first time since 1912 that hams had frequencies that low.