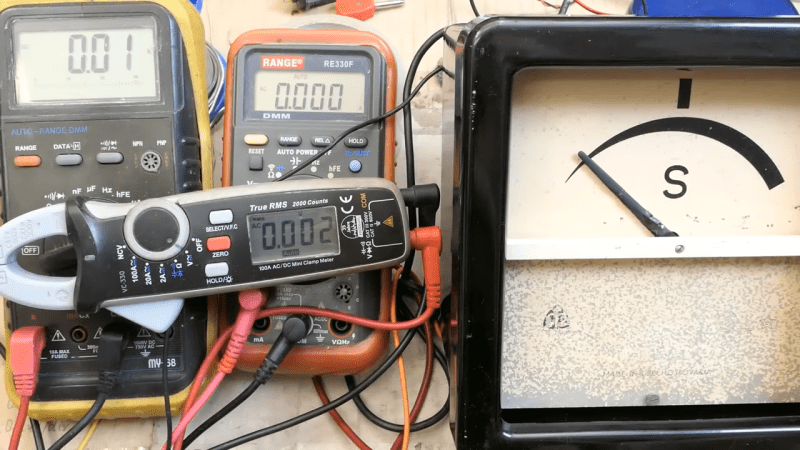

There’s nothing quite like old-school electrical gear, especially the stuff associated with power distribution. There’s something about the chunky, heavy construction, the thick bakelite cases, and the dials you can read from across the room. Double points for something that started life behind the Iron Curtain, as this delightful synchroscope appears to have.

So what exactly is a synchroscope, you ask? As [DiodeGoneWild] explains (in the best accent a human being has ever had), synchroscopes are used to indicate when two AC power sources are in phase with each other. This is important in power generation and distribution, where it just wouldn’t be a good idea to just connect a freshly started generator to a stable power grid. This synchroscope has a wonderfully robust mechanism inside, with four drive coils located 90° apart on a circular stator. Inside that is a moving coil attached to the meter’s needle, which makes this an induction motor that stops turning when the two input currents are in phase with each other.

The meter is chock full of engineering goodies, like the magnetic brake that damps the needle, and the neat inductive coupling method used to provide current to the moving coil. [DiodeGoneWild] does a great job explaining how the meter works, and does a few basic tests that show us the 60-odd years since this thing was made haven’t caused any major damage. We’re eager to see it put to the full test soon.

This is just the latest in a series of cool teardowns by [DiodeGoneWild]. He recently treated us to a glimpse inside an old-ish wattmeter, and took a look at friggin’ laser-powered headlights, too.

I worked at a decent sized data center in operations and had to learn how to manually transfer from generator, battery, or grid feed. Our automatic transfer switch never had a hickup but overnight guys had to be ready to go to the switchgear room and kick the whole DC from one source to another if all else failed.

Our syncroscope had a “ok to transfer” light that lit every few seconds, and as long as you hit the transfer button ONLY when it was lit then all stayed well in the world.

If it lit every few seconds the two sources must have been at _nearly_ the same frequency. You get a beat frequency on sync lights equal to the difference between the two sources.

Every electrical engineer/technician has a story about how some old mentor used to show off by syncing two generators together by their sounds before throwing the switch. The story also includes a prank where one student puts their foot on the damped pedestal and changes the sound, so the teacher throws the switch at the wrong moment and sparks fly.

Of course there’s a gap in the story: a person can hear the beat frequency of two sounds and match them to within a few hundred millihertz – that’s how you tune a guitar – but they can’t hear the phase because the sound isn’t coming from the AC voltage. The generators have to be pretty close to snap to synchronization without blowing the fuses anyhow.

You might be able to hear the phase of two signals if they are coming from different directions (left and right). If you turn around the phase on one side of a stereo audio signal, the spatial impression is changed and completely confusing (sound seems to come more like from the inside of your head rather than a virtual concert hall in front of you). I somehow doubt though that someone would be able to interpret that properly and precisely enough to synchronise a generator with mains… But who knows, maybe with a lot of practise?

Theoretically. If you plug one ear and put the other along the line of equal distance between the sound sources, you should find that the sound gets louder when the two generators are in phase. Shift your head a little to the sides and you should find the minimum points. If you manage to spot the interference pattern, you can deduce the phase difference by where you happen to be standing.

But the noise that the generator makes has too many frequency components that muddle up the pattern, the room has many echoes that change depending on where the people are standing, and it’s a mechanical noise that comes from how the generator was built, not from the AC voltage waveform.

Of course you could de-tune the generators slightly so you can hear a slow modulation and then hit the button at the right time so they snap together and synchronize by brute force – but that still doesn’t solve the problem of the sound not coming from the AC waveform, but something else like the fan blades of the generator.

I have used those things, or at least watched while other guys used them.

They still use the old school units in older power generating stations. If it ain’t broke, nobody’s going to replace it.