When the first radios and telegraph lines were put into service, essentially the only way to communicate was to use Morse code. The first transmitters had extremely inefficient designs by today’s standards, so this was more a practical limitation than a choice. As the technology evolved there became less and less reason to use Morse to communicate, but plenty of amateur radio operators still use this mode including [Kevin] aka [KB9RLW] who has built a circuit which can translate spoken Morse code into a broadcasted Morse radio signal.

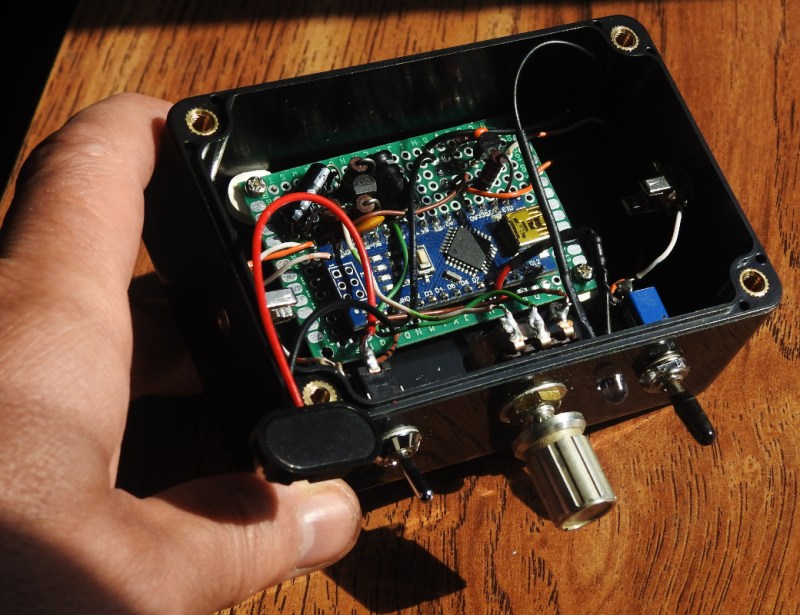

The circuit works by feeding the signal from a microphone into an Arduino. The Arduino listens for a certain threshold and keys the radio when it detects a word being spoken. Radio operators use the words “dit” and “dah” for dots and dashes respectively, and the Arduino isn’t really translating the words so much as it is sending a signal for the duration of however long each word takes to say. The software for the Arduino is provided on the project’s GitHub page as well, and uses a number of approaches to make sure the keyed signal is as clean as possible.

[Kevin] mentions that this device could be used by anyone who wishes to operate a radio in this mode who might have difficulty using a traditional Morse key and who doesn’t want to retrain their brain to use other available equipment like a puff straw or a foot key. The circuit is remarkably straightforward for what it does, and in the video below it seems [Kevin] is having a blast using it. If you’re still looking to learn to “speak” Morse code, though, take a look at this guide which goes into detail about it.

Thanks to [Dragan] for the tip!

Thanks for posting. I’ve had several comments from hams who’s physical limitations do indeed impede upon their enjoyment of their favorite mode. They were excited about this project getting them back into it. Exactly what I’d hoped for. Mission accomplished.

Kevin, KB9RLW

Ultra cool! Such a simple idea, so elegantly realized. This is a great example of deciding when to switch from discrete analog components to microcontrollers. He preserved only the amount of circuitry needed to condition the signal so that the AVR could do the rest of the work, and probably saved a ton of tweaking the circuitry. He also produced a project that is simple enough to be a gateway drug into CW radio.

When he makes his first contact with this, he seems just a bit embarrassed about how excited he was to actually use it. I fully understand. And when the person (W1AW-7) he makes contact with in a live stream recognizes his call sign, HE seems just as excited.

One comment on the contact, and this isn’t for KB9RLW, but for W1AW-7, when you send CQ at 20 WPM, and somebody answers it at 15 WPM (not the actual speeds, but just an example), the courteous thing to do is to continue the conversation at 15. Many people can’t reliably receive any faster than they can send.

One more thing for Kevin: I haven’t looked at your code, so you may have already done this, but I would have put some hysteresis in the threshold, so that if it triggers at, say 1V, it won’t un-key until the signal drops below 0.5V, and won’t key again until it exceeds 1V again. This should help with the “tail” of the “dah”, and might make it possible to eliminate the pot altogether.

I think he has an 18ms debounce in there. I know it’s not the same…

This is actually a pretty neat idea. Ham radio operators that go mountain topping in the winter (many of whom prefer to use Morse Code) no doubt suffer from cold hands, making it difficult to send cleanly. Even when it’s warm it can be difficult out in the boonies to set up a flat surface for a normal key or paddle. The main downside to this voice operated keyer would be if you’re trying to operate outside and it’s windy.

Plus points for any morse-code related project.

Sincere question… what is the point of the arduino? Couldnt it be replaced with a simple comparator with hysteresis?

Low component count, ease of assembly, flexibility in tuning and modifying the behavior of the keying. It’s so quick and simple to make changes in software vs analog electronics.

Please elaborate on why the transmitter were designed so extremely inefficiently back then.

I don’t think they were designed to be inefficient, but there may have been limitations in components / understanding in the very early days, that made them inefficient. Any other insights welcome!

The original spark-gap transmitters were pretty broadband (noisy) and took up a lot of specturm when in use. Not much issue when they were few in number and limited in range. But that also means that a lot of your energy was wasted (in a sense, AM was also wasted energy in a redundant sibeband, which is why SSB became popular with Hams, or Vestigial Sideband Modulation for Analog TV)

Once tube-based transmitters were available, they were phased out in the 1920’s and outlawed in 1934.

They had no other way to generate signals. Eventually they had mechanical generators that ran at high speed, but limited to low frequencies. Tubes allowed for better signals and higher frequency. “CW” means “continuous wave” of tubes, as opposed to the very messy spark signal.

You’d generate a wideband noise, and then hope a tuned circuit or the antenna would clean it up a bit. The receivers were coherer, which recovered the signal. It was awful, but what was there. And everyone jammed into a small segment of the radio spectrum.

And hams complained when King Spark was banned.

“And hams complained when King Spark was banned.”

Operators on sea, mainly, I believe.

Thing is, the quenched spark transmitters they used were much more rugged than tube-based transmitters. Let’s just think of the environment. Shaky sea, salt water, high humidity.. That’s why they liked to keep them for so long.

On sea, maintainance of a quenched spark transmitter was possible. Fixing a broken tube, not so much. We’re talking about big linear tubes, of course. As big as a bucket or a big bottle.

Speaking under correction, of course. This was before my time.

There were three popular spark transmitter types, actuality.

Since the online dictionaries aren’t really dependable, I add the German terms I know of in parentheses.

I hope I get things together correctly (fingers crossed 🙂🤞)

– spark gap transmitter (Funkenstrecke)

Very primitive, causes a rattling/crackling sound. Like little explosions. Works like a jammer. Very broad band.

– quenched-spark / quenched spark transmitter (Löschfunkensender)

Used damped waves. Uses multiple little sparks, hence it makes tones. Morse telegraphy was possible. Sounds a bit nicer compared to the predecessor.

On an oscillograph, the signal looked a bit like the “play” triangle on a VCR/cassette player. The cleaner signal was audible in an AM receiver (musical tone), like a crystal radio, could be sensed by a coherer etc.

It essentially was like a spark, as the name suggests.

The Titanic used it, I believe. The signals were non-CW. It was sounding morse telegraphy, so to say. But not clean as a sine. Rather, like a frienly sounding buzzer, but at 1000 Hz or so. Not humming.. Not sure how to explain. There are recordings/replicas of it on the web.

– arc emitter/arc transmitter (Lichtbogensender):

Uses hydrogen in a tube of glass. Glows blue-ish. Could be modulated. Similar to a radio tube. Undamped waves, could be used for Continuous Wave transmissions.

PS: There also was the alternator technology, as used by SAQ Grimeton.

Hmmm. Maybe we can finally find out what the Beach Boys were trying to say in their song “Surfin’.”

https://youtu.be/vhin9nxKoNM?t=6

“Umm, bah, dit di dit.”

Don’t know about the Beach Boys, but Rush’s YYZ took its opening rhythm from Toronto airport’s navigational beacon, which transmitted “YYZ” in Morse.

Or Flash and the Pan’s ‘Down among the dead men’ which is about the sinking of the Titanic.

Towards the end of the song there is some Morse code pips to be heard (probably SOS).

To nitpick, you generally don’t broadcast on ham radio. Broadcasting is one to many, hams talk one to one. There was a time of ham broadcasting, the germ of commercial broadcasting, when hams realized more people had receivers than transmitters. But that was soon banned.

The one exception is stations like W1AW that broadcast bulletins of interest to hams. I think they get special dispensation.

Don’t think that is true, but am not licensed.

In any legislation I can think of, yes, you need to identify yourself as the transmitter of a signal, but whom you aim that at is totally not subject of your license to use the spectrum.

Counterexamples include the bulletins you’ve mentioned, but also contesting and typical operation in modes like FT8.

What is true is that you must not build a commercial broadcast station, and depending on band and local legislation, you might need to yield the channel occasionally.

Yes it’s true. Broadcasting is one way. Ham radio is two way. Calling into the void in the hopes of getting a reply is not broadcasting.

All radio services have their own rules. Broadcasting is one, and different from two way radio.

Licensed since 1972.

Now we have a “I say this, you say the opposite, but have a counterexample to your actual claim” situation. Can you point to actual regulation?

Note that I’m not heads-on with you; it feels like you’re hitting the *spirit* of amateur radio very well with your statement. But: A lot of ham comms *are* broadcast. Or what exactly is APRS? APRS is just broadcasting of packets over a network in a flooding manner.

If that’s not a broadcast, I don’t know what would be. Also, most APRS transmitters *are* automatic stations, and do not partake in any two-way comms.

So, I’m really asking you not whether you are *sure* you’re right (you sure seem to be! That would also, no offenses, match the average experience I’ve had with long-term radio operators – immensely routined, but very sure what they do is right, even in the face of contradicting math ;) ), but whether you could point me to the authorative scripture on that issue.

Note that the 47 CFR 97.113 (b) only prohibits broadcasting *for the general public*; that does not say it’s not OK to broadcast, as long as the *intended range of listeners* isn’t “the general public”, i.e., calling into the void in hopes of some radio person somewhere else picking it up *is* OK – that’s gonna be an amateur.

I think amateur “nets” qualify as broadcasting, since you’re talking to everyone who’s tuned to that frequency at the moment. Completely legal. The distinction that was made for hams was that we could not transmit music, since that would clearly compete with commercial radio.

Speech to text is a thing, and certainly text to international morse is trivial- there is at least one web site that has “translated” public domain novels to Morse.

The beauty of Morse is that it is on or off- anything (light, sound) can be encoded. Blinks, grunts, so even if you can’t speak per se but can make any movement intelligible . Very cool project

Well.. as long as you are speaking your CW might as well power your radio by voice too.

https://hackaday.com/2013/11/26/amateur-radio-transmits-1000-miles-on-voice-power/