Today, it’s easy to take realistic visual effects in film and TV for granted. Computer-generated imagery (CGI) has all but done away with the traditional camera tricks and miniatures used in decades past, and has become so commonplace in modern productions that there’s a good chance you’ve watched scenes without even realizing they were created partially, or sometimes even entirely, using digital tools.

But things were quite different when King Kong was released in 1933. In her recently released short documentary King Kong: The Practical Effects Wonder, Katie Keenan explains some the groundbreaking techniques used in the legendary film. At a time when audiences were only just becoming accustomed to experiencing sound in theaters, King Kong employed stop-motion animation, matte painting, rear projection, and even primitive robotics to bring the titular character to life in a realistic way.

Getting Physical

As you might expect, the stop-motion puppets used in King Kong were all relatively small: ranging from a tiny figure used for the scenes where Kong was climbing the Empire State Building, to a two foot (0.6 meter) version used when the monster was at street level.

These puppets were built with an internal metal structure, known as an armature, that used ball joints to achieve a high level of articulation. There was even a diaphragm in the chest that could be moved to make it look like Kong was actually breathing. The armature was then covered with cotton to add bulk, which could be formed into visibly defined “muscles” with the strategic application of string. A final layer of real rabbit fur helped give Kong a more lifelike appearance.

Katie mentions that the soft fur did pose a problem: you could clearly see the indents left by the animator’s fingers when they manipulated the puppets between frames. But as luck would have it, audiences interpreted what was essentially a production error as the beast’s fur rippling and standing on end, which actually added to the overall realism.

Full-scale versions of Kong’s hand, foot, and upper torso were also created. The hand and torso specifically were mechanized so they could portray rudimentary movement in the same scene as the actors, such as when Kong pulls Anne out of the apartment building through the window.

Perfecting Projection

As Katie explains, King Kong visual effects supervisor Willis H. O’Brien had already pioneered the use of stop-motion to bring giant creatures to life in earlier works such as The Lost World in 1925. But what set this film apart was how it combined the technique with footage of human actors.

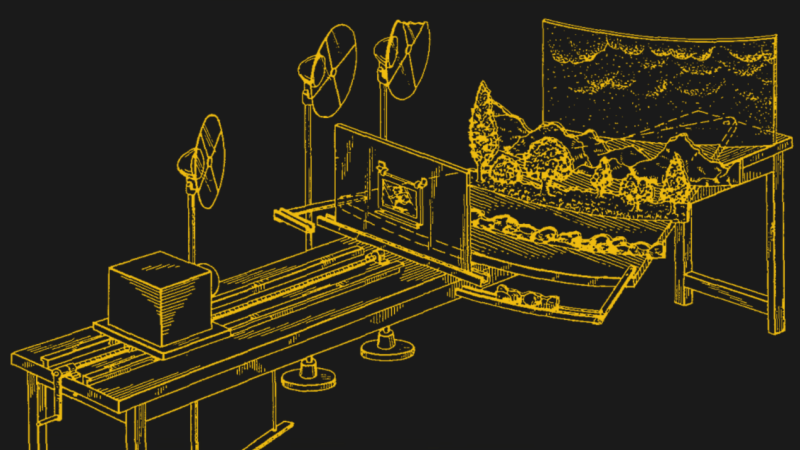

One of the ways this was accomplished was through rear projection — the completed stop-motion segments of Kong would be projected onto a translucent screen from behind the set. From the camera’s perspective the actors would appear in the foreground, and the stop-motion puppets, now enlarged many times their original size, would seem to be behind them.

This could be thought of as the analog version of today’s “green screen” techniques, but with the added bonus that the actors could see the projection and respond accordingly. In fact, in that regard it might actually be more accurate to compare it with the recently developed “LED wall” sets used in big-budget science fiction shows such as The Mandalorian and Star Trek: Strange New Worlds.

The technique could also be used in reverse — with a miniature projector and screen used to place footage of the actors into set with the puppets. By advancing the projector frame-by-frame in conjunction with the movement of the puppet, it would give the impression that Kong was interacting with the human actors.

A Lasting Legacy

A film using any one of these techniques would have been impressive to audiences in 1933. But the way O’Brien and his team managed to combine them, sometimes all within the same scene, redefined what the fledgling medium was capable of. Thanks in large part to their work, King Kong is still considered a seminal work in the field of visual effects nearly 100 years after its release — and is often listed among the greatest movies ever made.

“I REMEMBER WHEN AL JOLSON RAN AMOK AT THE WINTER GARDEN AND CLIMBED THE CHRYSLER BUILDING. AFTER THAT, HE COULDN’T GET ARRESTED IN THIS TOWN.”

OK now that the obligatory Simpsons quote is out of the way if you really want to understand how amazing King Kong (33) was watch Kind Kong (76), not a good movie but you would be amazed by how little special effects seem to have changed since the first King King. The people who worked on King Kong (33) were true artists.

76 was a better movie than the Peter Jackson Kong abomination.

I was an Extra in the ’76 Kong Movie.. I got Squished by a Giant Foot.. That entire back lot is now Condo’s

Progress I guess..

Cap

OMG! Are you alright!?

No, he is half left. …….. I’ll let myself out.——>

The miniturisation on King Kong is impressive, but for an engineering feat you’ll struggle to do better than the dragon in Fritz Lang’s 1924 film Die Nibelungen. You can see it in action in this clip

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=45-8eZViYOE

but far more impressive are the engineering diagrams showing the dozen or so men seated inside and operating it.

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-xM5CmoqpLWk/UKbOIJB9uWI/AAAAAAAAD5A/X-h4AEpgOP0/s1600/Siegfried+dragon+schematic.jpg

I remember touching one of the original King Kongs when it’s owner, Philip Jenkinson, brought it to a lecture he was giving at Southampton University in 75/76.

The special effects in King Kong 1933 were brought to life through the use of stop-motion animation by Willis O’Brien and his assistant animator, Buzz Gibson.[1][2] Mighty Joe Young (1949), on which O’Brien is credited as Technical Creator, won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects in 1950. Credit for the award went to the film’s producers, RKO Productions, but O’Brien was also awarded a statue, this time proudly accepted by him. O’Brien was assisted by his protege (and successor) Ray Harryhausen and Pete Peterson on this film, and by some accounts left the majority of the animation to them. Raymond Frederick Harryhausen[3] (June 29, 1920 – May 7, 2013) was an American-British animator and special effects creator who created a form of stop motion model animation known as “Dynamation”.[4] Harryhausen’s works include the animation for Mighty Joe Young (1949) with his mentor Willis H. O’Brien (for which the latter won the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects); Harryhausen’s first color film, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958); and Jason and the Argonauts (1963), which featured a sword fight with seven skeleton warriors. His last film was Clash of the Titans (1981), after which he retired.

* References:

1. King Kong (1933 film)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Kong_(1933_film)

2. Willis H. O’Brien

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willis_H._O%27Brien

3. Ray Harryhausen

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ray_Harryhausen

4. Ray Harryhausen, Whose Creatures Battled Jason and Sinbad, Dies at 92, by Patrick J. Lyons May 7, 2013 [Warning: May be paywall restricted for some viewers.]

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/08/movies/ray-harryhausen-cinematic-special-effects-innovator-dies-at-92.html

Did you see the first episode of season 3 of ‘the mandelorian’? Awful non-CGI puppets still exist in the entertainment industry. Those bits were so bad that you wonder why absolutely nobody stepped in.

Those monkeys in the tree, goddamn that was awful.

Kukla Fran and Ollie was once great entertainment. Bored me as a kid. Now I know I’ll pass on the Star XXX franchises.

I took it more as maintaining the original films’ look.

Almost vindicating the originals by way of “no, those weren’t bad puppets, those aliens really looked like that!”

Harryhausen is great. Go check out ‘first men in the moon’ great movie.

Also honorable mention to last show that leaned heavily on practical puppetry: Farscape

Who needs CGI when you can use guys in rubber suits:

Say hi Godzilla.