Before the Internet became the advertisement generator we know and love today, interspersed with interesting information here and there, it was originally a network of computers largely among various universities. This was even before the world-wide web and HTML which means that the people using these proto-networks, mostly researchers and other academics, had to build things we might take for granted from the ground up. One of those was one of the first search engines, built by the librarians who were cataloging all of the research in their universities, and using their relatively primitive computer networks to store and retrieve all of this information.

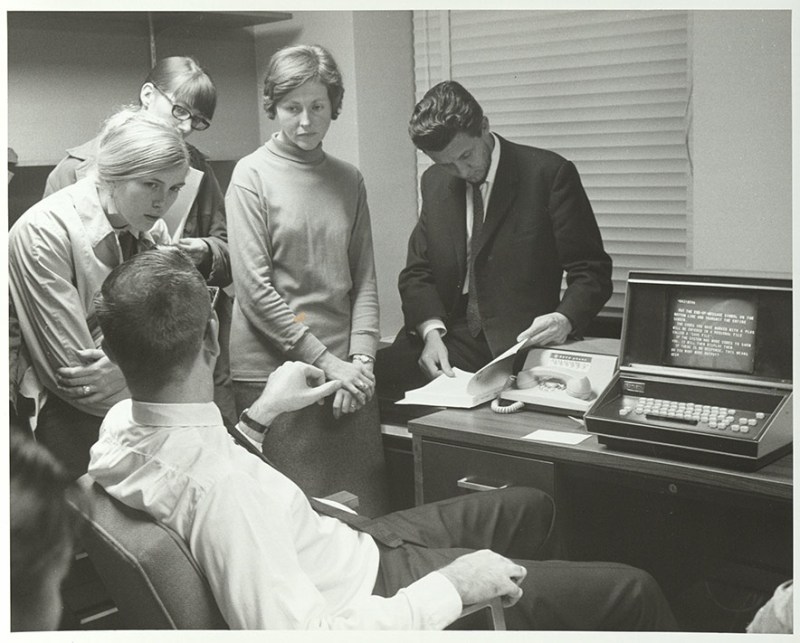

This search engine was called SUPARS, the Syracuse University Psychological Abstracts Retrieval Service. It was originally built for psychology research papers, and perhaps unsurprisingly the psychologists at the university also used this new system as the basis for understanding how humans would interact with computers. This was the 1970s after all, and most people had never used a computer, so documenting how they used search engine led to some important breakthroughs in the way we think about the best ways of designing systems like these.

The search engine was technically revolutionary for the time as well. It was among the first to allow text to be searched within documents and saved previous searches for users and researchers to access and learn from. The experiment was driven by the need to support researchers in a future where reference librarians would need assistance dealing with more and more information in their libraries, and it highlighted the challenges of vocabulary control in free-text searching.

The visionaries behind SUPARS recognized the changing landscape of research and designed for the future that would rely on networked computer systems. Their contributions expanded the understanding of how technology could shape human communication and effectiveness, and while they might not have imagined the world we are currently in, they certainly paved the way for the advances that led to its widespread adoption even outside a university setting. There were some false starts along that path, though.

Desk Set, 1957. YT has it in their “Buy, Rent” stuff I did not know they have.

Hepburn FTW. One her best, and still carrying Tracy.

There was a similar installation in Germany, called the Forschungs-Informations-Zentrum (FIZ – research information center) in Karlsruhe, that provided the (rather expensive) service of free text search on scientific publications, including return of abstracts and the place from which to order the respective book or magazine or article. I had the honor to use it during my high school and university times after bothering the local librarians in the 1980s and beginning 1990s.

Oh, do I remember that. You had to do a course on effective usage of the expensive system before you were allowed to use it.

Cool, I wonder if it was available online via Datex-P, too.

Because, Datex-P was an X.25 network available since 1980. Commercial and professional users used it a lot. Universities, too. It allowed accessing databases from all over the world, by dialing a local PAD. All it needed was an NUI and and a terminal (+acoustic coupler for direct dialup or gateway of another network).

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datex-P

If I’m not mistaken, many libraries of the 1980s or 1990s, say the Badische Landesbibliothek, had serial terminals installed already. They replaced traditional filing boxes over time. Not sure if they provided a Datex-P access, however.

The first large scale library cataloging operation was OCLC which was incorporated as “Ohio College Library Center” in 1967. The first site to on-line catalog it’s records was Ohio University’s library in 1971. OCLC originally used customized terminals communicating in block mode daisy chained on multi drop RS-485 (?) loops bridged via WAN connections. As the ARPA IP network transitioned to the global public Internet, OCLC transitioned to incorporating global member institutions networked via the Internet, changing “Ohio” in its name to “Online.” Later, the name was changed to simply “OCLC.” OCLC still exists in 2023.

Auto correct got me. I typed “its” but it auto correct “fixed” it for me and I didn’t catch the change until my comment was already posted.

My neural autocorrect fixed it while reading it: didn’t notice it.

Neat. Now I know what that initialism means. And I remember, pre-internet, how challenging it was to find out where a copy of an article was (first in the card catalog, and then…to the reference desk!)

[my daughter is a middle school librarian]

Interesting article that covers the inception, usage, student reaction and legacy of the SUPARS system, but not a thing about any insight into the technical aspects of the system apart from that it apparently ran on a System/360.

What language was it written in, database structures, terminal installations, sample user session printout would all be keenly interesting to a lot of HaD readers I’m sure.

Love the Bell 103A Modem. Yes, kids, that’s a 300 baud modem. At least, the top half of it. There’s another box, equal size, under the table. Full of cards filled with film caps and pot-core inductors. And transistors! No ICs in the Bell System yet.

https://kimon.hosting.nyu.edu/physical-electrical-digital/items/show/1490

I recognise that keyboard: I’ve got one somewhere loaded with a dozen or so VFD digits for a hex display for a very early home-build computer.

Gather around children and let me tell you about the library computer of the olden days:

You could search the University ibrary catalog for a book and even order it electronically. All you had to do is find the book on the catalog terminal, write down the information and walk over to the ordering system to type it in again.

Oh, and not all information was digitized. So it was a good idea to.still check the index cards.

I remember Hari Seldon visiting the one on Trantor 🙃