To say that desktop 3D printing had a transformative effect on our community would be something of an understatement. In just a decade or so, we went from creaky printers that could barely extrude a proper cube to reliable workhorses that don’t cost much more than a decent cordless drill. It’s gotten to the point that it’s almost surprising to see a project grace these pages that doesn’t include 3D printed components in some capacity.

There’s just one problem — everything that comes out of them is plastic. Oh sure, some plastics are stronger than others…but they’re still plastic. Fine for plenty of tasks, but certainly not all. The true revolution for makers and hackers would be a machine that’s as small, convenient, and as easy to use as a desktop 3D printer, but capable of producing metal parts.

If Cooper Zurad has his way such a dream machine might be landing on workbenches in as little as a month, thanks in part to the fact that its built upon the bones of a desktop 3D printer. His open source Powercore device allows nearly any 3D printer to smoothly cut through solid metal using a technique known as electrical discharge machining (EDM). So who better to helm this week’s Desktop EDM Hack Chat?

While Cooper is still riding high from the phenomenal success of the Powercore Kickstarter earlier this year, which brought in over $192,000, he certainly didn’t limit questions to his own project. He’s a firm believer in EDM, and whether you’re using his device or trying to DIY your own solution, he’s always happy to talk shop. That said, he did clarify at the beginning of the chat that the first wave of Powercores should be shipping before the end of July. The source for the project will be opened up around the same time as well, Cooper said it was important to the team that paying customers got their hardware before DIY clones started popping up.

Early questions in the chat focused primarily on the electrodes, which are naturally a very important element of EDM. As the sparks erode the workpiece, they also wear down the electrode itself. This needs to be compensated for during the machining process, or eventually the spark gap will become too great.

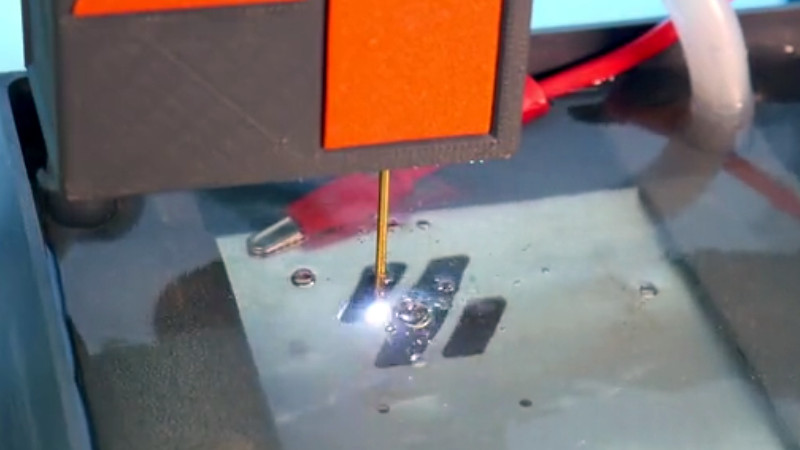

Luckily, a modified 3D printer has more than enough Z travel to counteract this issue. Cooper explains that they’ve prepared a special fork of the LaserWeb4 for use with EDM that will constantly lower the Z height at the proper rate to counteract the electrode itself becoming shorter over time. There was also discussion about electrode materials and shapes, including an interesting hollow variant that could have dielectric flushed through it while cutting deep holes.

While discussing what’s required to convert a standard 3D printer for EDM, Cooper explained that the process is quick enough that you don’t technically need a dedicated machine for it. This is made possible by the fact that, at least on the Ender 3 they’ve been using for testing, no firmware modifications are necessary. You simply remove the hotend and replace it with the electrode holder. That said, if you’re going to be doing a lot of EDM, it would make sense to have a dedicated setup, especially when you consider how cheap you can get an Ender 3 these days.

Eventually the discussion migrated towards the types of materials you can cut with a desktop EDM setup, and where the future might take things. Cooper says all of their testing with the Powercore has been with relatively thin aluminum, and indeed that’s all that’s been promised in the Kickstarter.

That being said, they’ve made progress with steel, though he thinks that switching the electrode from a brass rod to a thin wire is likely to be the key going forward. The far thinner electrode will cut faster, but the mechanics involved will be considerably more complex than simply bolting a brass rod to a 3D printer.

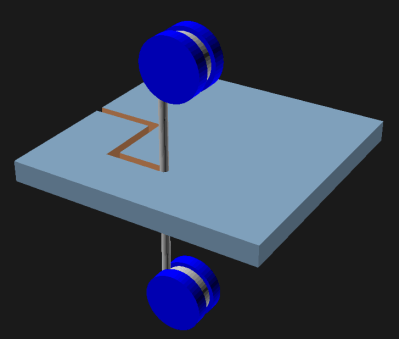

For one thing, the wire needs to be held in tension. That means it needs attachment points above and below the workpiece. The wire is generally kept moving as well, being pulled from a supply spool and getting wound around a take-up spool on the other end. None of this is impossible for a DIY machine, and we’ve already seen early attempts, but it’s going to take more work to make it practical on a hobbyist budget.

Which in the end, is sort of the point. By the end of the chat, which ran over two hours, the general feeling was that an exciting adventure was ahead. First generation DIY EDM rigs like the Powercore are only the beginning, not the final result. Once a few hundred hackers have these machines on their benches and can start working on them, it will pave the way towards the next evolution of the hardware. To put it another way, this is the Makerbot Cupcake era of home EDM — these are the days folks will look back on in 15 or 20 years as the first steps towards putting this powerful technology in the hands of the individual.

We’d like to thank Cooper Zurad for stopping by the Hack Chat, and wish him nothing but luck with the Powercore. We’re eager to see what the early-adopters will be able to do with the hardware, and also look forward to the design going open source so others can tweak and improve on it. There was a time when 3D printers and laser cutters simply didn’t exist outside of high-end R&D labs, and now we can pick them up on Amazon. It’s hard to say if the same will eventually be true for EDM machines, but we’re excited to find out.

The Hack Chat is a weekly online chat session hosted by leading experts from all corners of the hardware hacking universe. It’s a great way for hackers connect in a fun and informal way, but if you can’t make it live, these overview posts as well as the transcripts posted to Hackaday.io make sure you don’t miss out.

Brass seems an odd choice. Why not graphite or tungsten ?

Brass and copper wire coated with zinc is by far the most common used. It wasn’t too long ago those were your only two options.

I’ve heard of a copper-tungsten alloy but know little about it, it was a factor of a hundred more expensive, and too many people were complaining about how bad it is to work with.

I got a solid third of the way in before I realized the post isn’t about Electronic Dance Music.

Almost the same thing here. My RSS feeds are dominated by music tech, so I did a double-take when I noticed this headline.

(The mention of “brass” didn’t help me as I’m a sax player.)

So, to get back to the topic…

It does sound like “desktop anything” is a big part of what makes this period of Maker Culture. At least, that’s how it feels in the FabCity movement.

The exciting times ahead are partly about doing things together.

Because we should.

Can an EDM *play* EDM? Modulate the spark as it’s moving so you can hear it buzzing out some Daft Punk.

Well if toothbrushes can do Daft Punk, why not a brass wire! :)

https://edm.com/gear-tech/daft-punk-harder-better-faster-stronger-electric-toothbrushes-cover

No surprise that Hackaday would trumpet a story like this. 😆

I would happily pay a few grand for a functional, reliable, and accurate benchtop WEDM.

I wouldn’t imagine a 3D printed jeweler’s saw-style wire edm would be too hard. Not very long reach, but would be a start for steel. A printed frame, one pid or stepper motor at the end of the wire pulling at a constant speed (maybe through ptfe?), three pulleys up top with the center one acting as a tension sensor, and a DC motor up top pulling a constant tension with a PID loop.

Of course, the details are what get us. How does one keep constant tension on such a tiny wire without slipping?

Maybe hard to find a benchtop one,

But HGR always has a few tons of edm machines laying around for sale. Many of them are CHEAP AF. If youve got a few grand, and room for the purchase in your shop….might want to familiarize yourself with the used/salvage equipment businesses near you.

Cool, now the HF band gets a new enemy in every other nerds home – so no more PV blaming by ham-radio people … (No sarcasm, just knowledge)

You won’t be waiting 3 weeks for that part to arrive. But you will be waiting 5 days for your part to finish. EDM is slow.

EDM has been commonlyish used for some years now to rifle barrels in the home gunsmithing world. It’s pretty cool. As simple as some salt water, an aquarium pump, a DC power supply, and a 3d printed mandrel wound with copper wire.

No… that would be ecm. Electrical chemichal mschining.

Thats method works my etching away material .

It seems interesting, but the limitation to very thin aluminum sheet raises the question: How often do I need a thin piece of aluminum with complicated cuts?

I can see an application for panelwork; even a thin sheet backed by 3D printed supports would look better than straight 3D printing. Also foldable brackets maybe

We already have a lot of great ways to make that kind of thing, albeit mostly unsatisfying to the authenticity-minded. A ScanNCut2 machine is pretty cheap and there’s lots of reflective decorative stuff to cut and and apply to prints.

Straight 3D printing is pretty great for anything 2D, though, because you can sand with a power sander to a good finish.

Everytime I see one of these posts about EDM I get intrigued until I read on and it’s wire EDM. Sinker/plunge EDM would be a lot more interesting. That’s how many, perhaps most complex injection molds are made.

I wonder how hard it would be to make a sinker EDM based around using one of those .5mm mechanical pencil graphite lead pieces. Maybe not the most amazingly accurate thing in the world but for home shop use probably good enough for most people. Bonus points if it can auto-reload from a hopper…

There is a potential to make a sinker and possibly simple wire type EDM using the Powercore power supply. The unit has some kind of current-sense output, so you can tell when the device is sparking. If that is used to trigger the feed hold on a GRBL controller then you’d be at least part way to a closed loop sinker (not sure about what logic would be needed to detect accidental contact and how a “back out” action would be triggered. This might take something more advanced than GRBL to handle… maybe the g-code could be generated for “pecking” motions to handle this?). For a wire-type setup the same signal could be used to both pause the X/Y axis steps and to trigger the wire feed control (when there is current flowing, stop the x/y and run the wire feed motor). That is one thing I want to play with when I get mine. I’ve collected the parts to build a grbl shield but haven’t assembled it yet. It would replace the 3d printer’s controller. I’m sure a lot of people are thinking along these lines.

Leverage the abundance of cheap 0.5mm graphite rods …. I love it!

Not much shows up in a quick web search except for this Hacaday article from a few years ago: https://hackaday.com/2019/05/13/prototyping-pcbs-with-electrical-discharge-machining/

There are a few links in the comments on that article.

https://www.homebuiltedmmachines.com/

This project is sinker/plunge EDM.

You’re not reading too closely then, as this isn’t wire EDM. Wire is where they might go from here, but currently it’s a brass rod electrode.

It appears that they didn’t reach out to the LaserWeb developers about their work, though. ☹

What about using disposable syringe needles, and pumping the fluid through it as well?

We use to cut parts from 0.8 mm thick Titanium sheet using a Mitsubishi wire-EDM. The wire was 0.15 mm diameter and those machines would go through miles of it!