Well, we’re just zipping right through this series, no? So far we’ve looked at various postal machines and how they work to flip mail around, cancel the postage, and sort it, all in a matter of seconds. We explored the first automated post office and found out why it was a failure, and we learned why it all depends on ZIP code. Now, it’s finally time for some really fun stuff: the stamp trivia.

Now I’m no philatelist by any standard, though I do have a few hundred stamps strewn about the house. The danger in philately is that you learn all sorts of cool things about stamps and their history, and you just want to buy more and more of them. So let’s go!

Hot Off the Grill

As relatively inexpensive as postage has been throughout history, it hasn’t always been cheap enough for some. Back in the 1860s, some people found ways to remove the ink from the cancellation and reuse stamps.

To make matters worse, at the same time, smaller post offices were going without cancellation machines altogether, doing everything by hand. But just add a tiny bit of ink eradicator, and the pen cancel was history.

Many different devices were created for which their inventors sought patents, but the one that rose to the top was Charles F. Steele’s grilling device. It worked by embossing the stamp between two rollers, one with a positive, raised number of tiny pyramids, and a negative roller with a matching array of pyramid-shaped pits.

The idea was that grilling stamps would break down the fibers, allowing the cancellation ink to soak through such that it could not be removed without destroying the stamp.

A number of experiments with grilling were done. The first grill, known to philatelists as the “A” grill, was applied to the entire stamp. But this weakened the stamps too much, and they ultimately tore and fell apart during production. Subsequent grills took up a much smaller area.

Grilling was ultimately a failure, but the idea of deterring stamp reuse lives on. Remember that Australian stamp I showed you with the (fully appropriate) upside-down cancel? If you look carefully, you’ll see the slits running through it like a price tag sticker. That’s one way of doing it. In 19th century Afghanistan, stamp cancellation involved removing a bit of the stamp, rendering reuse impossible.

In the Light

Preventing postage reuse is just one of the reasons the USPS considered additives to stamps. As mail volume increased in the 1950s, countries all over the world were looking for new ways that would speed up the process of sorting and postmarking mail.

They worked with Pitney Bowes to design a new facer-canceller machine that could find the stamp faster and more easily. Eventually the figured out that the answer lied in luminescence.

Stamps would receive a phosphorescent coating called a “taggant” that was only visible under UV light. The process of applying this phosphorescent coating would be known as “tagging” (PDF).

Testing was successful, and on August 1, 1963, the post office introduced the phosphorescent tagging of stamps with the 8¢ Air Mail.

The USPS soon broadened their use of tagging, and all Air Mail stamps were tagged after mid-1974. Then, after 1991, most stamps were tagged — all definitive and commemorative stamps, but nothing under 8¢, interestingly enough.

Tiny Print Stops Big Counterfeiters

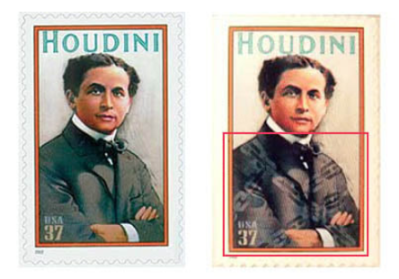

Of course, the USPS is always trying to come up with new ways of preventing counterfeit postage, which is a federal crime. Microprinting, as the name implies, is extremely small print on the face of the stamp — small enough that you’d need a microscope or at least a magnifying glass to read it.

Of course, the USPS is always trying to come up with new ways of preventing counterfeit postage, which is a federal crime. Microprinting, as the name implies, is extremely small print on the face of the stamp — small enough that you’d need a microscope or at least a magnifying glass to read it.

Think about all the tiny words that adorn the backs of US currency — postal microprinting is smaller than that. The idea is likely the same as with currency: when one tries to scan or photocopy the thing, the microprinting comes out as a line or a blur because it’s just too small.

The first stamp to feature microprinting is the 1992 Stream Violet shown here. Afterward, many instances of microprinting appeared within the design itself. The USPS has since moved on to printing alphanumeric combinations like USPS, 4EveR, 4evr, et cetera.

Freshly Scrambled Indicia

Freshly scrambled what now? Indicia just means distinguishing marks, though it also refers to those markings you see on bulk mail in the place of stamps.

Scrambled indicia is a process by which a hidden image is printed on a stamp that is scrambled, rendering it invisible to the naked eye and unable to be copied or scanned.

It was introduced September 18, 1997 with the U.S. Air Force stamp. The scrambled indicia can be viewed with a special lenticular decoder, which makes us wonder if any lenticular sheet would work.

The USPS has also used secret marks in the past to distinguish stamp issues and prevent counterfeiting.

Ice Cream and Other Delights

One of the coolest things about stamps is that they commemorate pieces of history both large and small. Moon landing? You know there’s a stamp for that. Progress in electronics? Stamps were there. Ukrainian soldier flips off a Russian warship? Oh yeah.

Stamps celebrate so much, and most people probably don’t give them a second glance. So what are some of the other cool issues throughout history?

One of my favorites has to be Frozen Treats, which came out in 2018. It’s the first (and I think only) series of US scratch ‘n sniff stamps, though other countries have done similarly.

Did you know that scratch ‘n sniff technology was born in the 1960s? At the time, 3M and National Cash Register were trying to find better ways of keeping ink in little pockets on the paper for receipts and carbon copies.

Someone figured out that this microencapsulation process they developed could also be used for scented oils. Before the stamps were issued, the American Lung Association argued via letter that the stamp fragrances “may pose a risk for serious health problems”. But the USPS assured them that the coatings and print varnish had all been safety-tested.

As far as recent issues go, there’s a series that came out a month or so ago called Life Magnified that is just awesome. I bought an extra sheet just to keep around and look at. They don’t smell or make noise or anything, but they sure look cool.

That’s All, Folks

I hope you enjoyed this series as much as I liked researching and writing it. The USPS has a long and fascinating history, and we’ve barely begun to scratch the surface. Hopefully you learned a thing or two. I know I did.

The US also made a plastic film stamp.

https://www.mysticstamp.com/Products/United-States/2522a/USA/

Speaking of favorite stamps, I really liked the hologram NASA stamps way back in late 80s. The hologram were printed directly onto envelope rather than on separate stamp but I loved those images!

“Eventually the figured out that the answer lied in luminescence.” “the” -> “they”; “lied” -> “lay”.

And Doesn’t. Should be Do not/Don’t.

“. . . doesn’t smell or make noise or anything”

Q: How many grammar nazis does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: Too

(And poor grammar drives me nuts as well so don’t take the joke personally :)

Snail stickers!

How did tagging deter stamp reuse? Did the tag come off when the canceling ink was removed?

Ah, I see I missed the statements that tagging was for another purpose.