Woodworkers have always been very clever about making strong and attractive joints — think of the strength of a mortise and tenon, or the artistry of a well-made dovetail. These joints have been around for ages and can be executed with nothing more than chisels and a hand saw, plus a lot of practice, of course. But new tools bring new challenges and new opportunities in joinery, like this interesting “hammer joint” that can be made with a laser cutter.

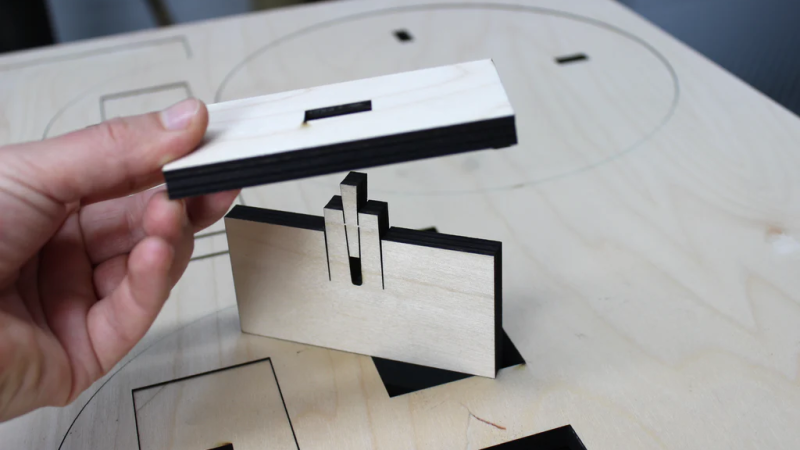

This interesting joint comes to us from [Jiskar Schmitz], who designed it for quick, solid, joints without the need for glue or fasteners. It’s a variation on a wedged mortise and tenon joint, which strengthens the standard version of the joint by using a wedge to expand the tenon outward to make firm contact with the walls of the tenon.

The hammer joint takes advantage of the thin kerf of a laser cutter and its ability to make blind cuts to produce a tenon with a built-in wedge. The wedge is attached to a slot in the tenon by a couple of thin connectors and stands proud of the top of the tenon. The tenon is inserted into a through-hole mortise, and a firm hammer blow on the wedge breaks it free and drives it into the slot. This expands the tenon and locks it tightly into the mortise, creating a fairly bulletproof joint. The video below tells the tale.

The hammer joint takes advantage of the thin kerf of a laser cutter and its ability to make blind cuts to produce a tenon with a built-in wedge. The wedge is attached to a slot in the tenon by a couple of thin connectors and stands proud of the top of the tenon. The tenon is inserted into a through-hole mortise, and a firm hammer blow on the wedge breaks it free and drives it into the slot. This expands the tenon and locks it tightly into the mortise, creating a fairly bulletproof joint. The video below tells the tale.

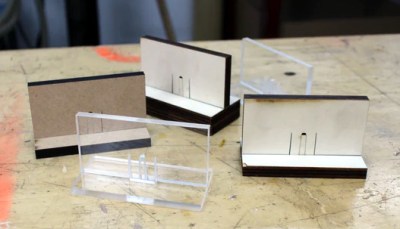

While the hammer joint seems mainly aimed at birch plywood, [Jiskar] mentions testing it in other materials, such as bamboo, MDF, and even acrylic, although wood seems to be the best application. [Jiskar] also mentions a potential improvement: the addition of a ratchet and pawl shape between the wedge and the slot in the tenon, which might serve to lock the wedge down and prevent it from backing out.

Last word of 2nd paragraph should be “mortise”.

+ for the quick assembly

– for the additional amount of offcuts

Don’t think it is really going to change the offcut waste % of a sheet very much, its a pretty small feature. Might even end up making better use of a sheet for some projects, though can also clearly pick geometry for which it will be creating more waste. But its a really clever idea that means no extra fixings are needed – and the costs associated with those probably exceed the wasted sheet in many cases as well…

What if the wedge were inside the boundary of the tenon, and a lever, rather than a hammer (or hammering against the edge with a pin behind the wedge, or a thin clamp around the wedge, or…) were used to wedge it? It would leave a hole in the tenon, but it would reduce the offcut size.

On 2nd thought, a wedge going the other way might not apply force in the right spot to spread the tenon with enough force… 🤔

Agreed, cute, but wasteful. It adds another 1/4-1/2″ of offcut along the entire length of the joint. A better way would be to cut the wedge(s) in the offcut from forming the tenons, or even the mortise if the material thickness is the same and the mortise is large enough.

Don’t let perfection get in the way of progress.

My first thought regarding this joint’s use in wood was to put some PVA glue into the gaps before hammering in the wedge. That might be even better than the ratchet idea proposed. Then again, the ratchet mechanism PLUS the glue – although overkill – would result in a truly unbreakable joint. Even given vibration, and expansion and contraction, the joint itself would forever be stronger than the pieces it joins.

In many cases, just glue will be as strong as any clever joinery. Especially with cheap mass-produced items. The wood can crush and crack when the joint is forced, where a simple glue-up would not end up broken out of the factory.

A glue strategy would be far better if you were shipping assembled articles, but joints like this are designed for assembly at the point of use. You can ship the product flat-packed, and the end user can assemble it without additional hardware, clamps, glue, skills etc.

Often when I buy flatpack furniture, they come with pegs and a little pouch of wood glue. You snip the corner off the pouch, squeeze it on the pegs and slap the thing together.

Particle board furniture isn’t designed to withstand any sort of stresses anyhow, so clamping would be totally superfluous.

Exactly. I did once make some large-ish laser cut plywood boxes with simple finger joints, reinforced at assembly time with some decent* PVA glue; later at some point it became desirable to replace one face of the box and I thought “oh okay we’ll just smash it off the rest and replace it” – yeah, well… even with completely unreasonable force applied, the only thing that happened was that the rest of the wood got smashed to splinters (at the cost of seriously great effort), while the bloody joints themselves stayed smugly and defiantly intact.

*there is such a thing as non-decent PVA glue: the version we tried to use before this one failed to keep even two large surfaces glued together face-to-face, subjected to hardly any stress at all… *sigh*

Some of the boxes I have don’t even have finger joints, just wood flush with wood and one or two tiny staples per seam. Pulling the joint apart usually splinters the wood first. Modern glues are pretty tough.

I like the idea of this, I bet you could reposition the wedge into the offcut so less of it is wasted (maybe leaving a tab so it doesn’t get lost). it would also reduce the height of the offcut by about half.

over all though, this is a pretty clean way to get a tenoned joint with minimal fuss.

The old fox wedge is clever because it can’t back out once you hammer it in. This can come loose and the wedge will wiggle out of the tenon unless you glue it in.

Had to look that one up. Pretty ingenious

I had to look up fox wedge too. In my opinion, Dude is spot on with his reasoning.

Clever. Though, it still has a laser charred edge. This technique could also be extended to work with CNC routing though the 1/8″/3mm kerf means more waste.

Look for Japanese joinery techniques. They are the best. What I find interesting is that because you use a laser or a cnc to cut the pieces it’s somehow a “look what I just did” , when this stuff has been around for 100s of years.

It might behoove makers to actually read and look at the way things are done in the many fields of things like making plastic mold, aluminum and sheet metal pieces. The nature of how these work when designed with the appropriate standards for bending, mild release, etc. Might actual help them!

Something that is happening here, that would be very difficult if not impossible to do with classic wood working, is the fact that the wedge can remain attached to the mortise before hitting it home with a mallet or hammer. IMNSHO, this is really the only reason to do it this way, as doing it with out the wedge connected to the mortise is really no different than how it is classically done.

I agree that the original maker should take a look at how these kinds of joints are made with out the use of the laser cutter, as it may improve the joint.

You could do it with a fine fretsaw and a drill.

Look at Shaker furniture as well. Flat-pack when Ikea was a dream.

Any thought to Morse tapers in wood or other so called locking tapers? Would be interested in how the angle of the wedge was derived.

Nothing special about the Morse taper. He just picked some numbers, said “looks good to me” and here we are.

He got his own stuff wrong anyway, so each size has a slightly different taper angle.