If you are designing a building and need to move many people up or down, you probably will at least consider an escalator. In fact, if you visit most large airports these days, they even use a similar system to move people without changing their altitude. We aren’t sure why the name “slidewalk” never caught on, but they have a similar mechanism to an escalator. Like most things, we don’t think much about them until they don’t work. But they’ve been around a long time and are great examples of simple technology we use so often that it has become invisible.

Of course, there’s always the elevator. However, the elevator can only service one floor at a time, and everyone else has to wait. Plus, a broken elevator is useless, while a broken escalator is — for most failures — just stairs.

Early Concepts and Patents

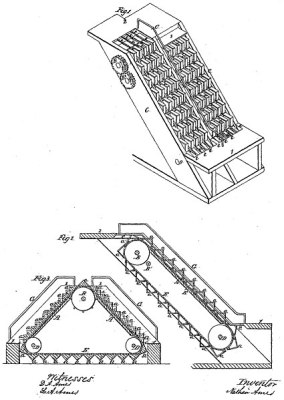

The story of the escalator begins in the mid-19th century. In 1859, Nathan Ames, a patent attorney from Saugus, Massachusetts, patented the first known design of an “escalator,” though he never built a working model. His design, called the “revolving stairs,” was quite speculative. He suggested the device would be either manually powered or work with hydraulics.

It wasn’t until the late 19th century that designs resembling modern escalators emerged. In 1889, Leamon Souder patented the “stairway,” which featured a series of linked steps. Like Ames, Souder never built a model of his invention. He’d later patent three other proto-escalator designs, including two shaped like a spiral.

By 1892, the patent office granted a patent to Jesse W. Reno’s “Endless Conveyor or Elevator.” A few months later, George A. Wheeler patented his design for a moving staircase, which was never built but influenced future developments. Charles Seeberger bought Wheeler’s patents and collaborated with the Otis Elevator Company to create a prototype that incorporated Wheeler’s ideas.

Jesse W. Reno created the first working escalator, which he termed an “inclined elevator.” In 1896, he installed it at Coney Island, New York City. This early version was essentially a belt with cast-iron slats for traction that moved along a 25-degree incline.

Charles Seeberger and Otis Elevator Company produced the first commercial escalator in 1899. This model won first prize at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle. Unlike Reno’s design, which was also at the Exposition, Seeberger’s escalator had flat, moving stairs and a smooth step surface without the comb effect seen in modern escalators. Attendees of the exposition could also see escalators from the Link Belt Machinery Company, Piat, and Hallé.

Piat, a French firm, had installed a “stepless” escalator in Harrods back in 1898. It had a leather belt, and — reportedly — employees had to revive unnerved patrons who rode it with free smelling salts and cognac.

Several companies went on to develop their own escalator products, often under different names due to trademark rights held by Otis. For instance, the Peelle Company called their models the Motorstair, and Westinghouse referred to theirs as an Electric Stairway, while Haughton Elevator had the delightfully simple name of Moving Stairs. Otis lost their trademark in a 1950 case Haughton Elevator Co. v. Seeberger where the court confirmed that escalator had become a generic descriptive word.

Some old escalators, including the one at Macy’s Herald Square in New York City, still operate today. It opened in the 1920s but was retrofitted with metal steps in the 1990s. You can see it below from — not kidding — The Escalator Channel.

The Core Components

An escalator is essentially a continuously moving staircase powered by an electric motor. The main components include steps, tracks, handrails, and a drive system. Each of these plays a crucial role in the seamless operation of an escalator. The main structural component is called a truss and is typically a hollow structure that runs the length of the escalator and supports the straight sections of the track.

The tracks guide the movement of the steps. There are two sets: one for guiding the steps up and another for guiding them back down. This creates a continuous loop that the steps ride.

Steps are the most visible part of the machine and are usually made from a single piece of die-cast aluminum or steel. They are linked together like a chain and mounted on tracks. Each step has wheels on the underside that roll along these tracks, allowing the steps to remain level while moving along the inclined path.

The handrails (part of the sides known as the balustrade) move in sync with the steps because the pulleys that drive them are on the same motor. The steps emerge from and disappear under the landing platforms at each end. The landing platforms have a comb to stop large things from entering the machinery. Many escalators also have a sensor, so if something unexpected enters the comb, the escalator will stop.

All About the Movement

Of course, the heart of it all is the motor. It is often under the top landing platform along with the drive gear. Another gear that reverses the direction of the steps.

The magic of an escalator’s movement lies in its looped system of steps. One track guides the two wheels in the front of the step that form a drive chain, and another guides the two back wheels. By controlling the vertical distance between the tracks, the steps can be made to lie flat or stand up.

If it doesn’t make sense, check out the animation from [Jared Owen] below.

The Future

It doesn’t seem like the escalator is going anywhere soon. However, there are always developments to make them safer, more efficient, and faster. Of course, today’s escalator will have much more control and monitoring via the network than the Macy’s building engineer could have dreamed of. Some escalators can now control their speed depending on the size of the crowd or even stop when no one is using them.

Want to really understand what’s inside? Why not print a model? Or, go to the woodshop and build a torture device for your Slinky.

Featured image: “Escalators 1” by Eric Pesik

The Budapest metro still has wooden escalators that move scarily fast! Though the stations are DEEP underground so the extra speed is appreciated!

“The landing platforms have a comb to stop large things from entering the machinery. Many escalators also have a sensor, so if something unexpected enters the comb, the escalator will stop.”

No YT link due to the squeamish but there’s one of a Chinese woman with baby going down that door at the head of the stairs. Baby survived (someone grabbed it), she didn’t.

Personally Satisfactory and Futurama have the better people mover with tubes.

I remember at the World Expo 67 (Montreal, 1967) a young boy riding the elevator in the USSR pavilion got the toe of his sneaker caught in the landing comb of the escalator and it wouldn’t let go. The boy cried out “help” and two Russian guards grabbed him and pulled him off the escalator, which ripped off about an inch from the toe of his sneaker and ate it.

The boy had to walk around the expo with one foot sticking out.

(As it happened the boy curled his toes back in the shoe, so that no toes were left in the machinery, but it was that close.)

Nowadays escalators have sensors.

I always wondered why there happened to be two Russian guards stationed at the top of the elevator.

That kid… is BACK ON… the escalator!

” You can see it below from — not kidding– The Escalator Channel. ”

They also have a Golf Channel.. Why Bother?.. I’ll take the Escalator Thank you..

Cap

Another hazard of escalators is people who are seemingly unaware of how they work. People stop after stepping off of the escalator causing a pileup as the escalator continues to deliver people to the already occupied space. I’ve seen such situations where the escalator is part of a queue.

BTW, why is it we call downward moving stairs “escalators” shouldn’t they be called “descenders” or something similar?

Because it’s the same thing but in reverse.

By the same token, you should call a lift a lower when it goes down, or a tractor a pusher when it’s in reverse gear.

“Because it’s the same thing but in reverse”

Then, shouldn’t they be called, “rotalacse”.

B^)

We can get away with it because some part of the mechanism is always escalating?

from French: “escalier” is just “stairs”, not “climbing”.

If you follow it even further to Latin you get “scala” for ladder, which comes from “scando” for climbing. Most of the modern words for ladders or stairs trace back to proto-indo-european words for climbing or jumping.

There’s a difference in how languages “see” things. French, English, Italian etc. describe things by what they’re used for, whereas languages like German or Finnish name things by what they are. An “escalator” is etymologically a “go-up-thing”, whereas the Finnish “liukuportaikko” fundamentally means “thing of many sliding boards”, and the German “Rolltreppe” means “rolling steps”.

Ahh. But “to climb” is not the same as “to ascend”.

You can absolutely ‘climb down’ a ladder. It still makes proper use of the root words.

An escalator is etymologically a “climb from one platform to another of a different height” thing just like a ladder is.

Everyone I know calls the people movers at the airport “slidewalks”, Al.

I’ve seen them called “travelators” too.

And lots of fun sliding down the hand rail and flying off at the bottom! Just don’t do it with polyester pants, else the threads melt together. Yeah… polyester pans…. it was a couple generations ago.

I do wish slides were a common route of transportation.

You know I used to get the words escalator and elevator confused and one day I tried putting Aerosmith’s “Love in an elevator” into practice and, well, let’s just say I’m not allowed back in that mall.

B^)

We’ve had these things for over a century, and they still have not figured out how to make the handrail travel at the same pace as the stairs? Why? How hard can it be to get that gear ratio correct?

All, why do say the macy’s is metal? I was there just some 2 months ago, and on the upper floors its all wooden goodness. Pretty cool to see.

As for “patented the first known design of an “escalator,” though he never built a working model.”

Patent trolling much … I’ll write a patent, for a working warp drive. I don’t have to build it, but if you try to build one too, I get to troll you! Sillyness. Sad to see the patent office slacking even back then.

If you can provide the theoretical framework and explain the technical details of the warp drive – go for it. Then, someone who has the resources can buy it from you and build it!

I think it worked as intended.

I’m always astounded when an escalator is broken and they insist that you go to the other end of the building to use those stairs because they can’t imagine people just using a broken escalator as stairs.

Rather, they’re afraid that it might break more, or start rolling backwards with the weight of the people on it.

There’s another escalator fanatic youtube channel in Japanese. The guy has like 20K videos of escalators from all over the country – it’s madness, and my toddler absolutely LOVES it. Nice article by the way, i’m off to 3D print one right now.

Some stations on the London Underground still had wooden escalator steps last time I rode it

>> Some escalators can now control their speed depending on the size of the crowd or even stop when no one is using them.

When it opened in 1968 the Old Mill subway station in Toronto had escalators that ran in either direction. Most of the time they did not run at all, but if you stepped on a sensor pad at either the top or the bottom they would start up in the appropriate direction, and would run long enough to get you to the other end, plus a little bit.

I don’t know exactly when they were converted to regular one-way constantly running escalators.

When 2 persons arrived at the same time from opposite side and both engaged in the escalator, maybe ?

I was in a high-end fashion mall recently, and I realized that even their escalators stink like grease.

For an awesome walkway, look up the “trottoir roulant rapide”. Provided a fantastic ride, though sadly not for everyone I read.

I like an escalator because an escalator can never break, it can only become stairs. There would never be an escalator temporarily out of order sign, only an “Escalator temporarily stairs. Sorry for the convenience.”

I came here to either find, or make this comment. Mitch Hedberg, RIP.

I had to use the elevator because the stairs where out of service.

1. The escalator at macys in NYC still has wood stairs it is even right there in the YouTube thumbnail. I think it’s only the top 2 floors though the rest are metal.

2. The basement is Macy’s in NYC has a bar and accepts macys store credit card. Shopping with the wife was never better. The longer she took the more it was her fault for how intoxicated I got.

3. Somewhere- maybe DC metro or maybe Chicago or even maybe it was Europe somewhere the escalators have motion sensors so if no one is around they don’t move. Smart.

4. At airport the horizontal ” escalator ” yup it’s a peoplemover. And, people! It’s. It not a darn ride! If you still walk on it instead of standing there looking around you will arrive much faster.

5. Unapologetic New Yorker: escalators or people mover stand to one side so people can get by. Geez.

3. We have lots of those in Helsinki.

5. That’s just common sense. Our escalators even have a guide telling you to stand on the right.

Spiral escalators!

https://www.mitsubishielevator.com/products/escalators/spiral

Ah, escalators. My biggest gripe (probably driven mostly off the DC Metro) is that it seems to take forEVER to repair them (maybe that’s a muni worker issue, dunno?). SO…towards that end, can’t they be made much more modular so “they” can remove a large section and replace it? Spoken out of ignorance, sure, but…