Polynesian cultures have a remarkable navigational tradition. It stands as a testament to human ingenuity and an intimate understanding of nature. Where Western cultures developed maps and tools to plot courses around the world, the Polynesian tradition is more about using human senses and pattern-finding skills to figure out where one is, and where one might be going.

Today, we’ll delve into the unique techniques of Polynesian navigation, exploring how keen observation of the natural world enabled pioneers to roam far and wide across the breadth of the Pacific.

Unbounded Exploration

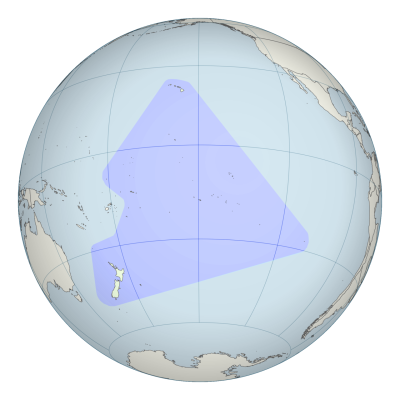

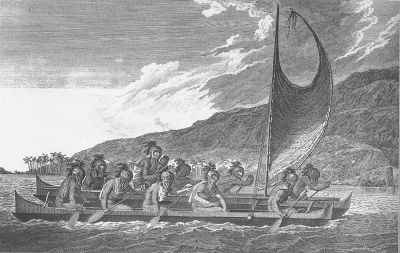

The Polynesian people, inhabiting the islands in the Pacific Ocean, embarked on epic voyages across vast distances well before the advent of modern navigation tools. Their navigational skills were pivotal in discovering and populating far-flung islands.

Hawaii is perhaps the best example of Polynesian navigational prowess. At a distance of over 2,000 miles from other land masses, it’s practically impossible to get to Hawaii unless you know where you’re going. And yet, evidence suggests that Polynesian navigators were able to find their way to the area’s island chains by 500 A.D., and perhaps even as early on as 100-200 A.D. All the more impressive is that these great distances were travelled without so much as a compass, sextant, or a map.

The essence of Polynesian wayfinding lies in the deep understanding and observation of natural signs. The oceans, the sky, and even wildlife all provided clues that could be read by a skilled observer. Today, we’d never think to use these methods. We can use satellites to plot ourselves as a glowing blip on a map, and make our way around staring at a screen. But with no maps or screens to look at, Polynesian wayfinders instead turned their gaze to the world around them, turning up all kinds of useful environmental flags to help them find points of interest.

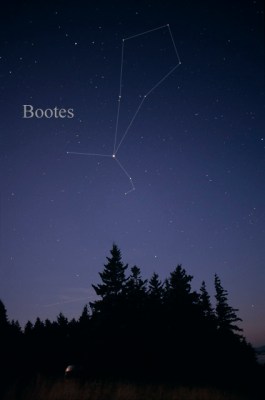

Some techniques are common across many cultures. Astronomy proved as useful to the Polynesian culture as it did any other, with stars useful as navigational beacons as they shined at night. Astute navigators would gain an understanding of how the stars rose and set depending on one’s own position. Certain stars proved useful for getting to certain locations. Arcturus was known as a guiding sign to Hawaii, and termed Hōkūleʻa by Polynesian navigators of yore. Those that left Tahiti by boat could simply sail to the east and north until Hōkūleʻa appeared directly overheard. The star is north of the equator by the same number of degrees as Hawaii. Thus, once one was underneath the star, one could be sure they were at the right latitude, and merely needed to sail west with the wind until Hawaii appeared on the horizon.

Other techniques are more unique. Patterns in the ocean swell could hint at distant land. Sit in any university-level fluid mechanics course, and you’ll learn about vortex streets, and how an obstruction in flowing water creates patterns downstream. The same effects are at play in the ocean, where flow around an island might create a pattern in the water readable at a great distance. Other effects could telegraph the position of land at great distance, too. For example, during the day, land is typically warmer than the surrounding water. This can create a thermal updraft, carrying clouds high in the air, while surrounding waters would have far lower cloud cover.

Perhaps most famously, the testicles were a key tool in the Polynesian navigational kit. This was a key technique to tracking ocean swells. These are long waves in the ocean that travel in regular patterns, generated by distant weather rather than local winds. They can propagate over thousands of miles, with patterns affected by distant land masses far beyond what the human eye can see. It’s believed that these navigators would sit in a canoe, cross-legged, using the testicles as a highly-sensitive detector for movements generated by the action of these swells beneath the ocean’s surface. Other accounts suggest the technique was performed standing, with the testicles acting as a sort of living plumb-bob.

Animals could be a great navigational aid, too. Pigs, with their keen sense of smell, could be used to determine when land was near. Birds and marine life were also helpful indicators. Certain birds were known to fly out to sea in the morning to fish, and return to land in the evening to nest. Thus, finding your way back in the evening could be as simple as following the birds in to land.

With the arrival of European explorers and colonizers, traditional Polynesian navigation saw a decline. However, there has been a significant revival since the late 20th century. Organizations like the Polynesian Voyaging Society have been instrumental in this resurgence. The historic voyages of the Hokule’a, a traditional double-hulled canoe, navigated using ancient techniques, have played a pivotal role in this renaissance, reigniting interest in traditional practices and strengthening cultural identity. With no living Hawaiians knowledegable of traditional techniques, Satawalese Master Navigator Mau Piailug of Micronesia joined the voyage to guide the way.

Today, Polynesian wayfinding is recognized not just as a historical curiosity, but as a valuable part of the world’s cultural heritage. It’s amazing to learn just what can be achieved through close and careful observation of the world around us. These traditional techniques are a true triumph of human ingenuity, a testament to what can be achieved with nothing but raw human ability.

Featured image: “Hokule’a arrival in Honolulu from Tahiti in 1976” by Phil Uhl.

Nice write up. I’d guess releasing pigeons from a cage beyond the 1/2 way mark might be useful. They’re either going to head back home or onward to the nearest land, whichever is closest, I guess.

“Perhaps most famously, the testicles were a key tool in the Polynesian navigational kit.”

Hmmm, wonder if the Titanic would have missed that iceberg if they tried that?

“I know we’re going the right way, I can feel it in my… well just trust me.”

Wrong ocean :(

Doesn’t work so far north, too much shrinkage.

Water was too cold!

Water too cold == Iceberg detected. Testicular navigation systems working as expected!

So there’s some truth to that Moana movie after all… good to know.

Yeah, she must’ve had some balls to make that journey!

You can also use them as bait if you run out of food. Watch for the sharks though.

Why they were depicted in the beginning intro credits of Star Trek Enterprise.

An apt metaphor for “epic voyages across vast distances”.

There also this:

“The oceans, the sky, and even wildlife all provided clues that could be read by a skilled observer. Today, we’d never think to use these methods.”

Yes, we still use some of those methods, find me a sailor that cant read the sky and I’ll doubt he sails. Sextants are a thing, even if they arent a primary method of navigation.

You’ll find them in Davey Jone’s Locker.

And harbor freight, though I am not sure how functional theirs is.

Probably need to add “testicles” to the tag…. Only way it will be remembered!

It was a typo, the Polynesians used “tentacles” from squids and octopuses as navigation aids.

B^)

+1 for an innovative use for “the boys”

The more you know…

Friend of a friend of mine sailed from CA to Hawaii in the 70’s by leaving west then following jet con trails overhead. Arrived alive. My friend, a naval aviator, was recruited to get back from E to W, much harder.

Before they discovered Hawaii for the first time I’m extremely skeptical the above methods would home them in to an unknown island 2000 miles away. I submit they were just exploring within their (impressive) comfort zone and happened upon it. Many such voyages were likely made, and some resulted in death. They couldn’t predict the weather far in advance, for example. In other cases maybe the food and water ran out, esp. when the wind failed longer than expected.

There was an entire book on this:

The Last Navigator, Stephen Thomas

There is another book named “Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia” by Christina Thompson which Chris Hayes interviewed on his podcast just a couple of weeks ago, https://www.msnbc.com/msnbc-podcast/why-is-this-happening/discussing-mystery-miracle-polynesia-christina-thompson-podcast-transc-rcna137041.

They had maps. Maps looked like twigs tied together. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Islands_stick_chart

Can’t draw a map of a place you haven’t found yet. One wonders why, once they found Hawaii, they ventured no further east…

looks like they did go further east. Claims of austronesian contact: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pre-Columbian_transoceanic_contact_theories