Sails typically bring to mind the high seas, but wind power has been used to move craft on land as well. Honoring this rich tradition, [Falcon Riley] and [Amber Word] decided to sail across Mongolia in “Moby the Land Sailing vessel.”

Built in a mere three days from $200 in materials they were able to scrounge up the week before, the cart served as their home for the 300 km (~186 mi) journey across the Mongolian countryside. Unsurprisingly, bodging together a sailing vessel in three days to traverse uneven terrain led to a failed weld to the front tire, but a friendly local lent a hand to get them back on the road.

Built mostly out of plywood, the fully-laden cart tipped the scales at 225 kg (500 lbs) and could still be towed by hand. Under sail, however, they managed 70 km in one particularly windy day. They covered the distance in 46 days, which isn’t the fastest way to travel by any means, but not bad given the quick build time for this house on wheels. We suspect that a more lightweight and aerodynamic build could yield some impressive results. Maybe it’s time for a new class at Bonneville?

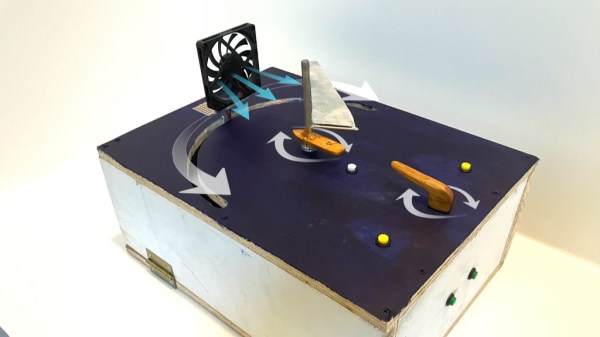

If you want to learn to sail in your own landlocked region, maybe learn a bit first? Instead you might want to build an autonomous sailing cart or take a gander at sailing out of this world?

[Thanks to Amber for stopping by to suggest some corrections!]

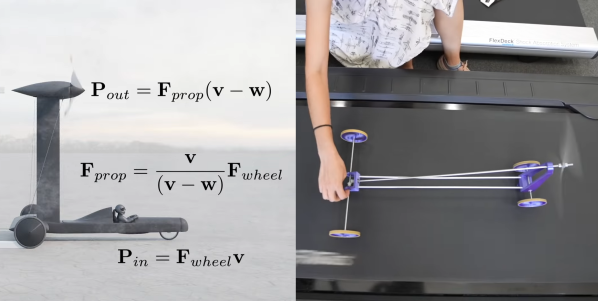

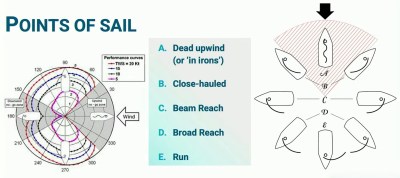

the first sails developed by humans were simple drag devices, sailors eventually developed airfoil sails that allow sailing in directions other than downwind. A

the first sails developed by humans were simple drag devices, sailors eventually developed airfoil sails that allow sailing in directions other than downwind. A