In the movie Conan the Barbarian, we hear a great deal about “the riddle of steel.” We are never told exactly what that riddle is, but in modern times, it might be: What’s the difference between 4150 and 1020 steel? If you’ve been around a machine shop, you’ve probably heard the AISI/SAE numbers, but if you didn’t know what they mean, [Jason Lonon] can help. The video below covers what the grade numbers mean in detail.

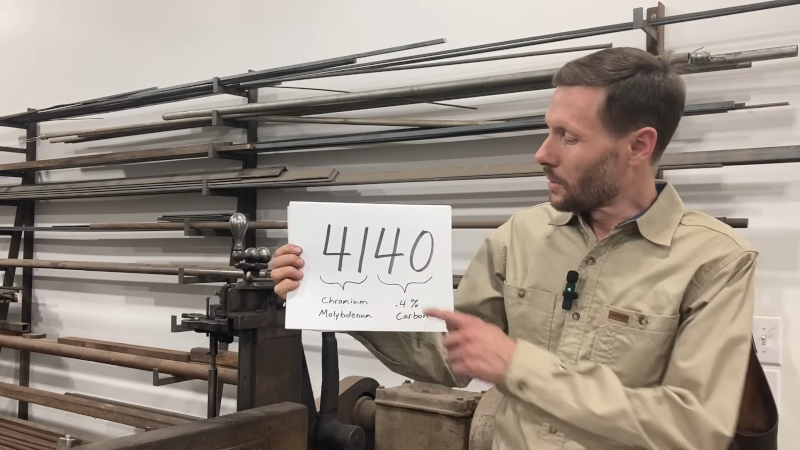

The four digits are actually two separate two-digit numbers. Sometimes, there will be five digits, in which case it is a two-digit number followed by a three-digit number. The first two digits tell you the actual type of steel. For example, 10 is ordinary steel, while 41 is chromium molybdenum steel. The last two or three digits indicate how much carbon is in the steel. If that number is, say, 40, then the steel contains approximately 0.40% carbon.

A common example of a five-digit code is 52100 steel. That’s ball bearing steel, and it has 1% carbon. You’ll notice that of the first two digits, the first digit changes when the main alloying element changes. That is, 2000-series steel uses nickel while 7000-series uses tungsten.

Tool steel has a different system, with a letter indicating the type of steel and a number indicating its alloy properties. Tool steel can be quenched in oil, air, or water. It can also be hot or cold drawn, and the letters will tell you how the steel was made. As you might expect, each type has different properties, which you may care about in your application.

For example, type W — water-hardened — isn’t used much today because it warps and cracks more often than steel produced with oil quenching.

If you want a list of steel grades, Wikipedia is your friend. You’ll see there are a variety of letters you can throw in to indicate hardness, and things like boron or lead added to the alloy, but these aren’t very common. Stainless steel also has a coding system that the video doesn’t cover, but you can find more information on the Wikipedia page.

If you want to work with steel, you’ll need heat. Next time you use tungsten steel, marvel at the fact that the Earth’s crust has about 1.25 parts per million of the rare element. Yet the world produces more than 100,000 tonnes of it a year.

An L in the designation means “leaded steel”. Lead may be toxic but it certainly improves the machinability. Source: my lathe. ;)

Is there anything they won’t find a way to sneak lead into?

“Lead free” ammo may still have lead compounds in the primer, and that’s the primary source of lead exposure from using firearms.

I’ve always wondered how they mixed the two. I’d figure the lead would vaporize at steel-melting temperatures.

The boiling temperature of lead is 2022K while steel generally melts below ~1800K, so it looks fine.

Yep. It’s steel.

Oh when oh when oh when will people (mostly US) learn that a leading decimal point should be preceded by a zero to improve its visibility. Looking at the heading photo I thought that the ’40’ meant 4% carbon.

As an American, I agree. I read it the same way. I always put a leading 0 on any decimal numbers less than 1 to make it easier to read.

In the still of the night, Ferruccio is steeling himsef to steal the steel.

Stiill?

I hope Ferruccio isn’t intending to steal my Stihl!

I should point out, the answer to the riddle of steel does occur in the original Conan movie (the one with Arnold Schwartznegger).

The newer remake was… unremarkable.

It was given to Conan by Thulsa Doom.

The fancier tool steels you see in stuff like nicer pocket knives can be more letters than numbers. See for example CPM-S30V. Though, in that case it looks like CPM is a brand.

Adding to that. I think I once had a little knife made from 8Cr13MoV which is a pretty literal description of the non-iron parts of the alloy.

I belong believe the CPM stands for ‘Crucible’ (It’s a Crucible Industries steel), ‘Powder-made’ (sintered), ‘Martensitic’. The S would be for ‘stainless’, the V for ‘Vanadium’, which is the greatest alloying element (4%) aside from Chromium (14%, which is covered by the S).

I have no clue what the 30 stands for though, as it’s 1.45% Carbon, 14% Chromium, 4% Vanadium and 2% Molybdenum, none of which line up with it.

It did get superceded around 15 years ago by CSM-S35VN, which added 0.5% Niobium, reduced Carbon to 1.4%, and Vanadium to 3%.

Importantly, though, NEITHER of these is a tool steel. They are custom stainless knife steels, and would not be particularly great for anything else – I wouldn’t even really want to use them in any blade longer than 12″/30cm, and even that would be pushing it for me personally.

High-alloy Chromoly+V steels have been popular for knives for a while now, and, while those three elements do form carbides and result in a strong, hard steel, especially with an ultra-high carbon content like that, hardness and toughness always oppose one another to a significant extent, and stainless steels always suffer from a degree of brittleness. So as a tool steel, or for longer blades and such, I’d stay far away.

Like most specialty steels, it’s good for its intended purpose, in this case certain kinds of knives, but much less so for others.

I trust steels a bit more than that, if the design is done right, and many so-called stainless steels are less brittle than many so-called carbon steels, as we’ve had improvements. Some shapes are just not meant to flex against impacts, unless you plan to make them out of silicone or something.

A couple years back, we even had someone take another stab at making a blade-focused steel, which turned out quite well in terms of pushing the envelope of tradeoffs. It was just given a name “Magnacut” instead of even trying to use numbers. This discusses it in detail. https://knifesteelnerds.com/2021/03/25/cpm-magnacut/

knife steel nerds is exactly that, knife steel nerds.

MagnaCut is amazing but probably a bit overhyped. It’s great for some things but bad for others. I don’t have the tools to experiment with it yet and the steel is rather pricey from my supplier. But it’s on my wish list to play with. From what I hear, the results are hit or miss due to low tolerances in heat threatment. Especially as a hobbiest this can be difficult as even large knife manufacturers get it wrong.

Well, I’m not a knifemaker, but I know some who are, and I got a positive impression from them. It sounds like once you know what to do, you can repeat that consistently and don’t feel as if your equipment is lacking or anything. With each steel, there’s always a few manufacturers that don’t spend enough time refining their process before shipping knives, or people who aren’t as exact in their details as they think. For a lot of people, s30v (not even s35vn) is the fanciest steel they use and they often use cpm154, ats34, d2, etc. And of course you can forge great results from all sorts of things that aren’t even as good as those on paper. But nevertheless, nerds consider those to be behind the curve, whether they prefer magnacut or something else for stock.

I have a kershaw with it and a homemade one that was a prototype of a pattern I drew up. I’ve abused neither, nor tested their hardnesses. But making the latter and others like it was apparently no trouble, being less of a pain to grind than s30v at the hardness he got. I take it as a good sign that the heat treat was apparently not worth mentioning. He used a bit more aggressive angle in recognition of the better toughness, which seemed to go well. So it’s not necessarily even a problem to not hit the harder end of the range, if you’re at least decently inside it. It’ll be easier to sharpen that way anyhow.

My personal opinion is, a lot of times you’re going to be better off spending more on the things that don’t cost you much or any extra labor but directly improve the value. Even if you’re not selling, you might as well have nice scale material and a nice steel if you’re putting all the effort in for the rest of it. Many people aren’t equally good at both knives and sheaths, so having someone else do the sheath could still be worthwhile. And anyway, you might be able to pick up steels at knife shows where someone got a bunch to sell in person without everyone having to pay shipping, which would help with the cost if your supplier is not giving a good one.

This is all subjective, of course. But it really does seem like a step forward.

4150 = 50CrMo4 0,5 % carbon 1 % chrom low proportion molybdenum

I have a ~1 kg cube of tungsten on my desk because it’s cool in its smallness. I wonder what volume of earth was dug up to make it, or how much steel it could have improved.

Do not pity yourself, how much gold and diamonds and other rare and useful for electronics or other industries are worn as jewlery, or worse, kept in safes and on the bottom of the seas?

Tungsten and gold are nearly identical in weight. Very difficult to measure the difference.

I’ve always liked lead:

1067g cube of tungsten (38.1 mm cube) density 19.3 g / cubic cm

1034g cube of lead (45 mm cube) density 11.35 g / cubic cm

Lead

Pro:

cheap, really really really cheap compared to tungsten

(lookup the price of lead flashings used on roofs)

Con:

toxic

not as small as a tungsten cube.

dents easily

Hobbyist knife maker here.

The annoying thing is that there are multiple ways to say the same thing.

O1 = 1.2510 = 100MnCrW4

O2 = 1.2842 = 90MnCrV8

3 different names for the exact same steel. The first one is the common name, the second the EU name, the third the “ingredient list”. If you make for example a knife, you put 100MnCrW4 on the blade, not O1. O1 is too common and looked down on. But you aren’t going to write 2MnCrV4 on a blade, you write CPM Magnacut on it. So the choice of which label you give it, depends on feelings.