Have you ever scanned old negatives or print photographs? Then you’ve probably wondered about the resolution of your scanner, versus the resolution of what you’re actually scanning. Or maybe, you’ve looked at digital cameras, and wondered how many megapixels make up that 35mm film shot. Well [ShyStudios] has been pondering these very questions, and they’ve shared some answers.

The truth is that film doesn’t really have a specific equivalent resolution to a digital image, as it’s an analog medium that has no pixels. Instead, color is represented by photoreactive chemicals. Still, there are ways to measure its resolution—normally done in lines/mm, in the simplest sense.

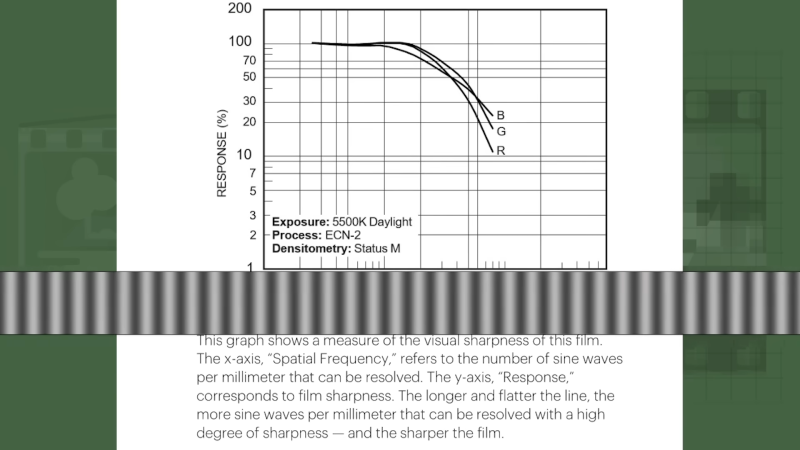

[ShyStudios] provides a full explanation of what this means, as well as more complicated ways of interpreting analog film resolution. Translating this into pixel equivalents is messy, but [ShyStudios] does some calculations to put a 35mm FujiColor 200 print around the 54 megapixel level. Fancier films can go much higher.

Of course, there are limitations to film, and you have to use it properly. But still, it gives properly impressive resolution even compared to modern cameras. As it turns out, we’ve been talking about film a lot lately! Video after the break.

Thanks to [Stephen Walters] for the tip!

Twenty years ago SMPTE performed extensive testing about the

matter.

I went to a college that has a film school and once in a while they would get original prints of stuff and show them on period projectors. They had a print of Faust from, maybe the 1930’s? It was so crisp and sharp it looked better than the imax Star Wars of the time. Same thing with a creature from black lagoon from the 50’s IIRC. It was really surprising what crazy good resolution old film has/had.

Monochrome films have a darker black level due to silver being more opaque than dyes. Older film even more so because the manufacturers weren’t as stingy with the silver as modern manufacturers.

Well, if your film or lens designs can resolve N line pairs per inch, you can still get more line pairs by using more inches.

This is true for films but not for lenses

When digitizing professional 35mms slides of wildlife, we decided that more than 3000*5000 wasn’t worthwhile because there was no point in digitizing the grain structure.

Wildlife photography is often done on quite fast (ie low res) film, because of the short exposures to freeze animals, and the long lenses.

As you hint, film absolutely has the equivalent of pixels and it’s called “grain”. Fun fact: look at the packaging; Kodak is strong in yellow and red, Fuji is strong in blue. Kodachrome of course iswas a whole ‘nother story.

For TV/Movies it doesn’t really matter over UHD resolutions. 8K isn’t noticable until around 150″s. The human eyes can only distinguish so much detail so it depends on size of the image and viewing distance A frame of IMAX format film has three times the theoretical horizontal resolution of a frame of 35 mm film.[ To achieve such increased image resolution, which IMAX estimates at approximately 12,000 lines (6,000 line pair modulations) of horizontal resolution (12K), 65 mm film stock passes horizontally through the IMAX movie camera, 15 perforations at a time. At 24 frames per second, this means that the film moves through the camera at 102.7 meters (337 ft) per minute (just over 6 km/h). In a conventional 65 mm camera, the film passes vertically through the camera, five perforations at a time, or 34 meters (112 ft) per minute. In comparison, in a conventional 35 mm camera, 35 mm film passes vertically through the camera, at four (smaller) perforations at a time, which translates to 27.4 meters (90 ft) per minute.

There’s a reason so few true IMAX theaters exist. The cost of well, everything. The screen size, the projector, and someone who properly knows how to operate one as a 2 hour movie would be 12km of film. IMAX digital projectors still don’t come close to film.

Just saw an original print of Lawrence of Arabia on 70mm film pat a local theater and the image was so sharp and crisp it looked like it was shot yesterday. Minus the occasional scratch marks and dust.

Sorry to be replying so late but where did you get an opportunity to see an original print of Lawrence of Arabia?

A remaster was made about 12 years ago and new prints struck from that but I would be excited to know a print with the original look exists and is being shown anywhere. That kind of thing is worth a flight. The remastered print ‘corrects’ some period artifacts and was digitally processed.

Reddit has a thread discussing it:

Hopefully Hackaday allows reddit links…

https://www.reddit.com/r/criterion/comments/18e2qzg/are_there_any_70mm_showings_of_lawrence_of_arabia/

In the same high res 65mm-70mm genre, the 2019 Apollo 11 documentary is a fun watch. It’s really cool to see the launch spectators at the launch pad in high-res era specific fashion as well as all of the launch footage.

https://m.imdb.com/title/tt8760684/

I occasionally watch rock concert videos from the early 80’s, and it’s sad how the transition to analog electronic video cameras did such a poor job of capturing important events. I know it was a necessary step in technology, but there’s whole era specific events captured with really poor resolution in that window of time. Then if you jump back to scanned film rock concerts of the 70’s, and the resolution is awesome.

But if you also look at audio, the same thing happened in the early days of MP3, Bluetooth, etc. The transition from analog to digital was rough on high fidelity.

Necessary steps in technology, but at a cost of resolution.

I have taken many tens of thousands of film pics, and never used 200iso film.

The more interesting number in this video is that kodak t-max 100 was 138megapixel (A film I sued a lot) – and can confirm that when I enlarged that to poster size it did look better than what I get from many digital cameras..

And I’d be using f1.2 or so…

H&W Control film was Agfa Copex used with H&W Control developer and would really run these numbers up.

Isn’t it more effective to blow the image/frame up first, then digitize ? Then the resolution becomes limited by the material used which the image is stored on i.e. the film material itself rather than the image resolution. Thus the best resolution will depending on the relative size of the surface imperfections/perforations on the film itself.

Yes, that’s what I have been doing; and contrary to movie magic, if the information is not there, making it larger won’t find it!

This is a very complicated topic. The practical resolving power of film is far less than the simple number convey. The MTF curves are created from exceptionally perfect sources. Something akin to chrome plated glass being contact printed in a laboratory. This situation is so ideal and abstract that it is not applicable. Some of the measurements are creating line-pairs small enough the film grain should be a problem.

The reality is that the lens is going to limit the quality of the image hitting the film.

I work with a lot of film, for photographed film a 1/2 frame image can be fully captured at a digital scanning resolution of 4k. That is still really impressive, but can be eclipsed by practical detail in a micro 4/3’s digital camera.

For the same back-plane area digital captures more detail. Films advantage is that negative can be HUGE in comparison to a digital sensor. There isn’t a digital equivalent to large format film or imax film.

Since optics are going to be the limit by area increasing the area increases the practical physical possible resolution.

Film has lots of amazing things going for it but absolute resolution per unit area is not superior to modern digital imaging.

Spy film.

“The reality is that the lens is going to limit the quality of the image hitting the film.”

This also used to be true for PAL video cameras, I think.

An recording done with an professional SD camera,

but with good optics and proper lighting could have had an surprisingly clear picture quality.

Better than an average consumer grade HD camera with a cheap lense and cheap photo sensor.

Unless being recorded on plain VHS, of course. I’m thinking of S-VHS and the professional tape types.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Video_tape_recorder

“the lens is going to limit the quality of the image hitting the film”

That’s what we were taught. A lens that could “match” the resolving power of fine-grain film (say, 64ISO or better) would be very, very pricey. But there are other reasons to use those films. I once shot a roll of Kodachrome 25 – brightly-coloured flowers, orchids mostly. Holy hell, they looked good.

And I once looked into getting a digital back for my Mamiya RB67. AUD$14K was a bit out my price range :-(

Those line pair counts assume a high contrast of 1000:1. It’s rare to have such contrast in real world. That’s why there is another measurement, for contrast of 1,6:1. So real life photograph with Fuji Color 200 has digital resolution of 21,5 megapixels. That’s typical value for 35mm color film. Now, if we pick a film that has lower ISO, it’s resolution rises because grains become smaller, and require more light for their photochemical reaction to occur. So for the same level of brightness one needs bigger aperture and slower speed, which flattens focus plane and makes camera more sensitive to any type of vibration. On the other hand faster, high ISO film has bigger grains, and thus lower resolution, but requires much less light.

In the end 35mm film is no better than modern mirrorless camera in terms of resolution. And the higher the ISO, the worse it gets. However, that higher resolution at high contrast has one practical use: storing lots of data in small space. Microfilm, microfiches and microdots all rely on that higher line density. Properly stored these media will stand the test of time better than any digital storage solution we currently use.

Someone mentioned that old film movies look much better than modern, digital ones. The reason is that even 21,5 megapixels 35mm film is 2,5 times more than 4k digital video at 8,3 megapixels. And 70mm film quadruples that. And the more contrasting image, the better the details – another advantage of film.

One last thing: does it really matter? We watch our digital images on digital screens that have lower resolution than the images themselves. When printing, we don’t use 6200DPI, and we don’t print large formats, usually. For example National Geographic magazine, known for its quality images is printed at about 150DPI. A photo printed with resolution of 400DPI on A4 size sheet has resolution of 11,56 megapixels. 400DPI for A4 was recommended to me as a compromise between file size and variability of human eyesight. Epson suggests to go as low as 240DPI, that’s about 7 megapixels. So yeah, in most cases high pixel count doesn’t really matter…

An interesting subject, but not spending an age watching a video which could be described in a few paragraphs of text. In the early 90s I remember there was a group interested in the effects of digital compression on films which relied on the ‘graininess’ of a movie to convey a specific atmosphere e.g. “Aliens”. So, yes, scanning the grain might well be important.

There are also those broad-range chromogenic black and white films to consider. I’ll use Ilford XP2 Super as an example because I have extensive experience with it, but I’m sure there are others.

This is nominally an ISO 400 film but it has a lot of dynamic range to spare. I’ve found you can expose it as if it were anywhere from ISO 1600 to ISO 25 and get usable images. (You can choose frame by frame and then process the whole roll with standard C41 process — no special development tweaks).

At 1600 it’s a little dim and very grainy but easy to fix with a response curve tweak, and as you go towards 400 things get more “normal”. Past 400, the more overexposed it is the finer the level of detail (at the expense of some dynamic range), but here’s the catch: You have so much dynamic range to spare that even exposing it at ISO 25 (four whole stops over nominal!) you still have more dynamic range than a human looking at a print under ideal light will be able to see.

In practice, this means you have to scan it at 16-bit grayscale and then tweak the response curve, but I’ve scanned some 6x9cm negatives at 4800 DPI with no visible grain and nice sharp edges which works out to something close to 200 megapixels.

In general (even when using film that isn’t so obsessively optimized for dynamic range) my big gripe about digital photography is not about resolution, it’s about dynamic range. Whether you’re in the darkroom or scanning your negatives and sending off for dye sublimation prints, you have so much more wiggle room with film on account of its having more dynamic range than a print can represent.

Film depends on the film and the way it is processed, but mostly it comes down to how big the chunks of the silver nitrate are on the negative. Slower films have smaller chunks and less grain. I got into shooting with Panatomic-X film with an ASA rating of 32, and super fine grain. We had an old 4×5 camera in the back room back in high school. No one was too interested in it, but I got some sheet film for it and went out into the desert in search of the perfect vista. The one thing that I recall about the first time I tried to make an enlargement, we also had one of those old beseler enlargers with the glass plates that no one wanted to use. I recall looing down with the grain focuser and turning the knob to what would have been razor sharp for a 35mm negative, you know, the spot that you pass and it starts to get fuzzy on the other side? Only this did not get fuzzy on the other side for about another full turn on the knob.

Another thing is now everything is color and in color film the grain tends to get masked by the fact that is is random and different for all three colors. It makes it a lot harder to see. Also the randomness in the grain makes black and white cinema from looking so awful. It is random on each frame and it tends to average out in your brain. Take any one frame that has not been digitally doctored and you will be amazed at just how bad it looks. Put a bunch together and add some motion to it and poof, it all goes away and it looks good.

My experience was, that my first 1.2 Megapixel digital camera made better pictures than the crappy pocket camera (ritsch, ratsch, klick, if you remember) I used in school days. Ok, it was no Minox.

So “calculating” a digital equivalent is indeed always dependent on the medium – Ilford Delta 3200 not to mention.

Taking the resolution rating where the MTF function has fallen below 20% is misleading. Although the film is providing some response at that spacial frequency, it’s not visually satisfying. A better point would be 50%, which would give the Fujifilm a resolution rating of 60 cycles/mm, the rough equivalent of a 12.4 megapixel digital sensor (ignoring the effect of the Bayer filter.)

So my Samsung S24 Ultra with 200mp sensor is about as good as 35mm on the 4:1 pixel binning 50mp setting? Good to know.

I’d like a second opinion on this 200MP claim, as the sensor is behind a tiny lens. The optical and dimensional accuracy required must be incredible! Is a 200 MP sensor way overkill for the quality of lens provided on the phone? Just saying, 30 years ago, we used to spend the equivalent of a modern, high end smart phone on glass alone.

With a 0.6 micron pixel size, theres going to be a heck of a lot of digital filtering going on in anything less than full sunlight. Ergo, in anything but ideal situations, it aint no 200MP camera. The Canon EOS R6 Mark II which is a full frame 24 MP camera, according to many having the least noise levels, has a 5.96 micron pixel pitch.

35mm is useless if you can’t shoot a decent selfie with it.

Even if there was enough light and everything about the sensor was perfect, then if samsung could make a lens with enough resolution not to limit that sensor, they should sell a scaled-up version for regular cameras because nobody has anything like that. I don’t see that happening.