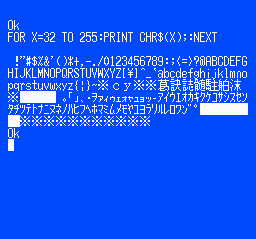

Sometimes, hardware projects get cancelled before they have a chance to make an impact, often due to politics or poor economic judgment. The Tsushin Booster for the PC Engine is one such project, possibly the victim of vicious commercial games between the leading Japanese console manufacturers at the tail end of the 1980s. It seems like a rather unlikely product: a modem attachment for a games console with an added 32 KB of battery-backed SRAM. In addition to the bolt-on unit, a dedicated software suite was provided on an EPROM-based removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation.

removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation.

Internally, the Tsushin booster holds no surprises, with the expected POTS interfacing components tied to an OKI M6826L modem chip, the SRAM device, and what looks like a custom ASIC for the bus interfacing.

It was, however, very slow, topping out at only 1200 Baud, which, even for the period, coupled with pay-by-minute telephone charges, would be a hard sell. The provided software was clearly intended to inspire would-be games programmers, with a complete-looking BASIC dialect, a comms program, a basic sprite editor with support for animation and  even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.

even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.

PC Engine hacks are thin pickings around these parts, but to understand a little more about the ‘console wars’ of the early 1990s, look no further than this in-depth architectural study. If you’d like to get into the modem scene but lack original hardware, your needs could be satisfied with openmodem. Of course, once you’ve got the hardware sorted, you need some to connect to. How about creating your very own dial-up ISP?

Where’s the SuperCon live stream?

B^)

It’ll take a month to send that via 1200 bps! ;)

Hi. Many may find it funny why 1200 Baud was used. That’s understandable.

However, the problem wasn’t computer technology being limited, but the medium – the landline.

See, many landlines had been of very poor quality. Bandwith was ca. 3 KHz, with noise and crackles.

So it made sense to use 1200 Baud, which was a Bell standard (Bell 202 Norm) and had used AFSK.

It used two tone pairs of 1200 and 2200 Hz, which did fit into 3 KHz range, but had enough spacing.

The signal-to-noise ratio was okay, in short. No DSP technology was required yet.

Going up to 2400 Baud would have been possible, but at cost of reliability.

Datasette systems had used 300, 1200 and 2400 Baud as well.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_202_modem

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITU-T_V.23

Forget the bit about the gamepad input because it would be trivial to make a keyboard for the PC Engine. The game port was merely GPIO and thusly it was software driven which means you could connect anything so long as your “game” handled the I/O.

Already done and documented.

https://github.com/pce-devel/PCE_Keyboard