If you want to play with radar — and who could blame you — you can pretty easily get your hands on something like the automotive radar sensors used for collision avoidance and lane detection. But the “R” in radar still stands for “Radio,” and RF projects are always fraught, especially at microwave frequencies. What’s the radar enthusiast to do?

While it’s not radar, subbing in ultrasonic sensors is how [Dzl] built this sonar imaging system using a lot of radar principles. Initial experiments centered around the ubiquitous dual-transducer ultrasonic modules used in all sorts of ranging and detection project, with some slight modifications to tap into the received audio signal rather than just using the digital output of the sensor. An ESP32 and a 24-bit ADC were used to capture the echo signal, and a series of filters were implemented in code to clean up the audio and quantify the returns. [Dzl] also added a downsampling routine to bring the transmitted pings and resultant echoes down in the human-audible range; they sound more like honks than pings, but it’s still pretty cool.

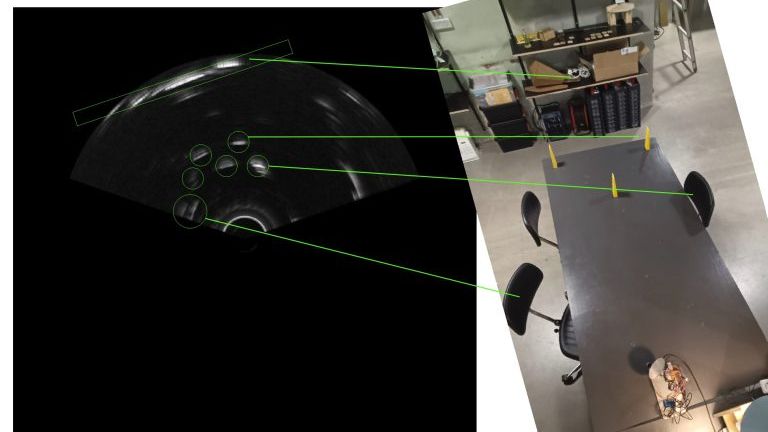

To make the simple range sensor more radar-like, [Dzl] needed to narrow the beamwidth of the sensor and make the whole thing steerable. That required a switch to an automotive backup sensor, which uses a single transducer, and a 3D printed parabolic dish reflector that looks very much like a satellite TV dish. With this assembly stuck on a stepper motor to swivel it back and forth, [Dzl] was able to get pretty good images showing clear reflections of objects in the lab.

If you want to start seeing with sound, [Dzl]’s write-up has all the details you’ll need. If real radar is still your thing, though, we’ve got something for that too.

Thanks to [Vanessa] for the tip.

Love the satellite dish – it sure works well too. I wonder for the future if there’s an analog “angle” to go at this, using a much higher frequency sound signal and an analog heterodyne to bring the sample rate down to something more reasonable and to narrow the beam width. I’m inspired. Excellent work.

There’s a reason these relatively low frequencies are used: High frequencies are attenuated much more by air. At a few hundred kHz the useful range is less than a meter. At 1 MHz, it’s a few centimeters.

What you might gain in resolution you will lose in range. Chose the frequency accordingly.

Part of why it’s more fun to play with in water as well

It’s a fat finger issue, and and editing issue, not a “spelling” issue. Possibly you are unaware that “o” and “i” are adjacent on a keyboard.

It’s a spelling mistake likely caused by a fat finger. The word in the article definitely doesn’t have the correct spelling in my book (a Funk and Wagnalls). A spell checker would have noticed the error, because it’s purpose is to check, you know, spelling.

U standardid speler ave kno imajination.

They’re just homebrew sonars, no?

An anicdote time, one that I’ve only recently seen the funny side of.

I once made a similar sonar (no where near as complicated) but it was on rails and so moved in 1dimension stopping to turn at intervals.

The crowning jewel was code that took the image and converted it from a circle section and overlaid it with each other. A lot of work went into the code to flatten the cone and turn it into a square.

Some of you will already be preparing a reply. It of course didn’t work after a couple weekends of intense work someone pointed out why. I didn’t need to transform the data it’s a circle section and can be directly overlaid to make a full mapping.

I was so crushed by my own stupidity I dropped the entire project.

It’s only “stupidity” if you give up, otherwise it’s a learning opportunity :)

Well I certainly learnt to not become enamoured by the task as interesting as it seems and forget the goal!

There’s plenty of times in computer vision when you

DOneed to flatten or widen stuff or correct lens distortion or flatten out perspective, so you’ve now got some useful skills.So a fish finder for your car or life lol.

It reminds me of a Hackaday article from years ago about someone who set up multiple Hot Wheels radar guns and built a simple phased array radar.