On 31 March of this year we had to bid farewell to Charlotte Elizabeth “Betty” Webb (née Vine-Stevens) at the age of 101. She was one of the cryptanalysts who worked at Bletchley Park during World War 2, as well as being one of the few women who worked at Bletchley Park in this role. At the time existing societal biases held that women were not interested in ‘intellectual work’, but as manpower was short due to wartime mobilization, more and more women found themselves working at places like Bletchley Park in a wide variety of roles, shattering these preconceived notions.

Betty Webb had originally signed up with the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), with her reasoning per a 2012 interview being that she and a couple of like-minded students felt that they ought to be serving their country, ‘rather than just making sausage rolls’. After volunteering for the ATS, she found herself being interviewed at Bletchley Park in 1941. This interview resulted in a years-long career that saw her working on German and Japanese encrypted communications, all of which had to be kept secret from then 18-year old Betty’s parents.

Until secrecy was lifted, all her environment knew was that she was a ‘secretary’ at Bletchley Park. Instead, she was fighting on the frontlines of cryptanalysis, an act which got acknowledged by both the UK and French governments years later.

Writing The Rulebook

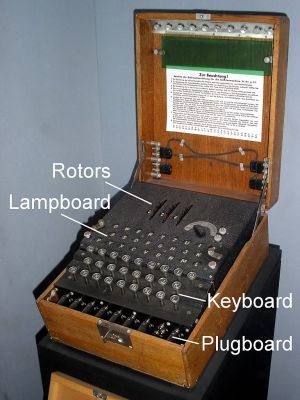

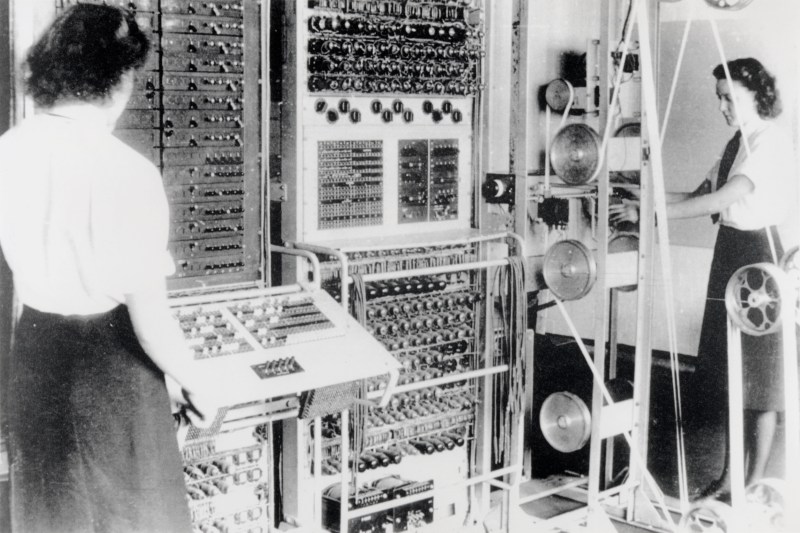

Although encrypted communications had been a part of warfare for centuries, the level and scale was vastly different during World War 2, which spurred the development of mechanical and electronic computer systems. At Bletchley Park these were the Bombe and Colossus computers, with the former being an electro-mechanical system. Both were used for deciphering German Enigma machine encrypted messages, with the tube-based Colossus taking over starting in 1943.

After enemy messages were intercepted, it was the task of these systems and the cryptanalysis experts to decipher them as quickly as possible. With the introduction of the Enigma machine by the Axis, this had become a major challenge. Since each message was likely to relate to a current event and thus time-sensitive, any delay in decrypting it would render the resulting decrypted message less useful. Along with the hands-on decrypting work, there were many related tasks to make this process work as smoothly and securely as possible.

Betty’s first task at Bletchley was to do the registering of incoming messages, which she began with as soon as she had been subjected to the contents of the Official Secrets Act. This forbade her from disclosing even the slightest detail of what she did or had seen at Bletchley, at the risk of severe punishment.

As was typical at Bletchley Park, each member of the staff there was kept as much in the dark of the whole as possible for operational security reasons. This meant that of the thousands of incoming messages per day, each had to be carefully kept in order and marked with a date and obfuscated location. She did see a Colossus computer once when it was moved into one of the buildings, but this was not one of her tasks, and snooping around Bletchley was discouraged for obvious reasons.

Paraphrasing

Although Betty’s German language skills were pretty good thanks to her mother’s insistence that she’d be able to take care of herself whilst travelling on the continent, the requirements for the translators at Bletchley were much more strict, and thus eventually she ended up working in the Japanese section located in Block F. After decrypting and translating the enemy messages, the texts were not simply sent to military headquarters or similar, but had to be paraphrased first.

The paraphrasing task entails pretty much what it says: taking the original translated message and paraphrasing it so that the meaning is retained, but any clues about what the original message was from which it was paraphrased is erased. In the case that such a message then falls into enemy hands, via a spy at HQ, it is made much harder to determine where this particular information was intercepted.

Betty was deemed to be very good at this task, which she attributed to her mother, who encouraged her to relate stories in her own words. As she did this paraphrasing work, the looming threat of the Official Secrets Act encouraged those involved with the work to not dwell on or remember much of the texts they read.

In May of 1945 with the war in Europe winding down, Betty was transferred to the Pentagon in the USA to continue her paraphrasing work on translated Japanese messages. Here she was the sole ATS girl, but met up with a girl from Hull with whom she had to share a room, and bed, in the rundown Cairo hotel.

With the surrender of Japan the war officially came to an end, and Betty made her way back to the UK.

Secrecy’s Long Shadow

When the work at Bletchley Park was finally made public in 1975, Betty’s parents had sadly already passed away, so she was never able to tell them the truth of what she had been doing during the war. Her father had known that she was keeping a secret, but because of his own experiences during World War 1, he had shown great understanding and appreciation of his daughter’s work.

After keeping her secrets along with everyone else at Bletchley, the Pentagon and elsewhere, Betty wasn’t about to change anything about this. Her husband had never indicated any interest in talking about it either. In her eyes she had just done her duty and that was good enough, but when she got asked to talk about her experiences in 1990, this began a period in which she would not only give talks, but also write about her experiences. In 2015 Betty was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) and in 2021 as a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour) in France.

Today, as more and more voices from of those who experienced World War 2 and who were involved the heroic efforts to stop the Axis forces fall silent, it is more important than ever to recognize their sacrifices and ingenuity. Even if Betty Webb didn’t save the UK by her lonesome, it was the combined effort from thousands of individuals like her that cracked the Enigma encryption and provided a constant flow of intel to military command, saving countless lives in the process and enabling operations that may have significantly shortened the war.

Top image: A Colossus Mark 2 computer being operated by Dorothy Du Boisson (left) and Elsie Booker (right), 1943 (Credit: The National Archives, UK)

Bro, you mad?

Dude, seriously, you going there over an article about a pioneer in cryptanalysis? Give Tucker Carlson a call, he’ll make you a star …

I am hoping that @Rick and @Titus431 are just bots, and not people who have been indoctrinationated in the “I can’t wait for history to repeat itself” view askew. I can’t believe I have to say that the Nazi’s were the bad guys in 2025, and that there is actually war heroes who fought against the bad guys. Of course there is a lot of grey area, but nothing even close to a justification of the Nazi party.

Errr. Sorry if I was unclear — I was trying to say that @Rick’s comment was … highly flawed (… crazy af). I guess it didn’t come out that way. I agree with 100% of your feelings.

Peace is not Natural, and will crumble often.

It takes a lot of dedicated People from all walks of life to try and put it back together.

Sometimes we can not ‘tell all’ about how Peace was achieved. Because ‘Not Peace’ will learn how to succeed.

It will always be this way. But we will never give up.

Ever

Cap

“Peace is not Natural”

Aren’t there just two species for fight each others in wars, though?

Humans (and apes) and ants?

I vaguely remember reading or hearing something like this.

The other conflicts in nature are to be said not to be “wars” as such.

They’re rather personal conflicts between individuals of same species (dominance etc), or conflicts between two different animal races.

Predators/prey relationships etc.

I don’t think ants really count tbh – they’re really much less individual, it’s more one nest fighting another.

Packs of animals will displace/kill other packs as well, but I think “war” just has a lot of meaning embodied in it that makes it hard to apply to animals incapable of humanity’s level of cooperation. For an inter-species war, the animals would need a way to distinguish between “them” and “us” which would require expressing that, and then communicating that concept – location alone would not be sufficient.

Chimpanzees will form groups of males, enter the territory of other chimp groups and attack and kill chimps, usually alone, from the other group. Sounds like small scale military operations. We’re no different, just smarter.

Personally, what I think is so tragic about war is that it forces men,-who have no personal argument with each other-, and which in otherwise could have been best friends, to fight each other.

It make me thinking about this scene from TOS, in particular: https://youtu.be/082elPIlBmM?t=186

One thing forgot: There’s this idea that wars produce “strong men”. But is that so, always?

How many men who returned from war were actually broken down, failed at re-integrate with friends and families? Had been treated badly, almost worse than the enemy?

How many of these brave men suffered afterwards, were afraid of being a threat to their beloved ones?

I think I haven’t the right to answer this questions, I’m afraid. Yet, still, I think they’re being worth of being asked. War changes people. To the better or the worse.

Without in any way making light of the suffering caused by war, I think the statement is probably true in the same manner that “evolution produces stronger species” – yeah individuals will suffer and die, but the group overall will either become stronger or die out. I don’t think anyone says “we should have wars to have stronger men” though, or at least I hope not.

@aleksclark Is this the only way, though? What I wonder is how things could have turned out if we had done the experiment of creating a peaceful society. At least once, in human history. To see how it goes?

What if the result had been at the end that we maybe would have had learned to feel empathy to great extent?

What if our society’s “religion” would have been based on team work and co-operation instead of territorial expansion and war making?

Couldn’t it have been possible that this would have had a very positive effect on our brain development, of our cognitive abilities? About life expectancy?

If we have had kept each others healthy for hundres or thousands of years instead of making everyone living in dirt and poverty?

Couldn’t this have had been much more of an evolutionatory accelerator than the war making had been?

What if humanity have had been “held back” by wars in reality, but we haven’t had a base for comparison to realize it?

What if our concept of evolution and “survival of the fittest” had been flawed?

Wasn’t it our mental power that finally made us humans “rule” the planet?

I mean, in the not so distant past, there was the philosophical concept of the “homo humanus”, the humanic human/human man.

A future stage in human development in which we had overcome our primitive insticts of hate and revenge.

In which we had reached a higher level of mind, in which we would have had mastered to integrate into our environment without destroying it.

@joshua plenty of people have tried, many times.

Start at Matthew, chapter 5 and related. That’s why the Germans understood they have been the bad guys, while others today are in the same position and don’t understand. Sadly a lot of people here in germany opt out of the “be peaceful” mindset, resulting in the only difference between being a “freedom hero” and a “monster” is if you kill your child before or after birth :-(

As a modern day German, I would never question that our predecessors were the bad guys here.

We learn that in school multiple times, watch WK2 documentaries on NTV/N24..

Heck, even our family members teach us about the past early on.

The “hero” topic is a though one, though. Heroism, as such, too. Very complex.

Historically, I believe, we Europeans had fought very bloody wars with the innocent being the victims very often. Then there was the colonial chapter, too.

Let’s just think about how many women and children had to suffer by wars started by men.

They had been killed, raped and kidnapped.. People with disabilities did suffer, too.

And even the good guys were only human, after all.

If I had to think about “heros”, I would think of astronauts/cosmonauts maybe.

But even those guys probably had a dark side of some sort, not sure. Again, it’s a though topic. To me/us, at least. Though I can’t speak for my fellow countrymen, I think. Sensitive topic.

Heroism, I mean, not the openly talking about WW2.

Not the least, because some nations define themselves through their national heros.

Eternal peace with endless resources did not end well: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Behavioral_sink

Did I miss something in the article? All it talked about was a) writing tracking information for obfuscated documents and b) paraphrasing already translated messages. Where’s the cryptanalysis?

Thanks for the article. Enjoyed getting a little glimpse behind the scenes.

Always have to roll my eyes at those who criticize actions of the past or spew ‘holier than thou’ comments when they haven’t walked in the shoes of people who were involved and the thinking at the time.

My grandma told me about how she, a little girl and her mother had a white blanked with them in winter, so they could hide in snow.

Because heroic allied fighter pilots were after them, in low flight, shooting at them with machine guns when they saw them.

Then there was a TV documentary that told that many German women and girls did commit suicide at end of war because of fear of being raped by the incoming, allied soldiers, especially from red army.

Then there were TV documentaries about helicopter crews in more modern wars were they threw their war prisoners out of helicopter, to increase the body count.. How many got medals for this achievement?

I write this down without judging, I wasn’t there, it’s merely a matter of facts told by others. It’s something to think about, simply. Heroism, propaganda, cruelty of war..

“Who haven’t walked into the shoes who were involved..” Right, spot on!

What I wonder about is how Betty Webb would think about herself, about her role in history.

Would she see herself as a “hero”, or if being interviewed at high age, would she have told us with a serious, slightly sad expression “No. I’m not a hero. I served my country, I did try to support the best in what I had believed in.”?

Please forgive me, but I think this a really interesting point.

From what I’ve learned by watching documentaries,

it’s not seldomly the case that heros at end of their lives aren’t proud about their actions and don’t see themselves as heros – even if they are, objectively speaking.

Not seldomly, they perhaps rather are being traumatized by war and all the horrible things they have seen and heard.

They wonder how much of an effect their work had,

how many lives had been saved or lost because of them.

If it had shortened war or not. Such things.

I probably shouldn’t write these lines here, but I can’t help but wonder.

Then the other end of the Scale.. Lets work in secret and make the Most Deadly Weapon ever seen by man, to finally stop the killing sooner.

Theory has, that many lives were saved by killing all at once.

War is expensive, Peace is Priceless.

I wish we could figure this out.

Cap

This is the single most idiotic thing I’ve read in a decade. Not just today. Not this week. A decade.

At first I thought it was some kind of bait to lure Poles just waiting for an opportunity to mention Marian Rejewski under every article about Bletchley Park. Then I started googling the alleged ethnic cleansing and, lo and behold, the only relevant information I found was an article from 2018 about false claims removed from Croatian Wikipedia (https://balkaninsight.com/2018/03/29/croatian-wikipedia-removed-claims-on-polish-genocide-over-germans-03-29-2018/). This together with the first comment under this article mentioning brave Croatians standing for their values during WW2 (Ustashe, anyone?) is starting to look like a pattern.

I hope you are kidding.

BTW, you can always fabricate reasons to invade other countries. Just like Austrian did, and many dozens of other politicians, all the way to now.

Something that’s always puzzled me is how people decode messages in a language they don’t know, e.g. Japanese with its three writing systems. Clearly it’s not the hurdle that it seems to me.

Hi. There are different versions of morse code alphabet, I think.

International, Cyrilic and Japanese among others..

The modern international morse code alphabet was being made by a German, Gerke, by the way. ;)

The US also have/had their own continental version used by railroad companies/telegraph lines.

That’s why the “HI” for laughing came to be in radio telegraphy, maybe.

In the original, wired telegraphy of the US, the same dot/dash pattern originally meant “HO”, because a third symbol existed (long dash ?).

A “HO” like Santa would say (HO! HO!). It’s just a theory, though. :)

Obviously knowing the language helps in several ways, but when you’re talking about modern cryptanalysis, it’s math before anything else. An encrypted message looks like a purely random stream of numbers, but any human language (or video file, or spreadsheet) will have not-at-all random statistical patterns, and that’s what you’re looking for.

If you happened to have the right Enigma settings for a message, the distribution of letters in the output would be glaringly different to any incorrect setting, so you’d know you’d cracked it; then you just pass the text to a German speaker.

Particularly in the case of Enigma it was useful to know things like German letter frequencies or the exact format of Wehrmacht field reports, but that’s more about having the right technical data than understanding German per se.

Put another way, you need to speak German to decrypt the German, but to decrypt Enigma you need to speak Enigma.

And if all you’re doing is transcribing CW then you just need to know the length of the dits, dahs and gaps

If you’d like to learn something, rather than simply foam at the mouth, check out the Friedman archives at nsa.gov.

William cracked Purple for the Army and Elizebeth broke the German South American spy codes for the Navy. After the Coast Guard was transferred to the USN, the two preeminent American cryptanalysts, husband and wife, were not allowed to discuss their work and did not do so. Even when William broke Purple he never said a word to his wife.

Read “The Woman Who Smashed Codes”

“What’s heroic about mass bombing of cities”

Stopping the mass bombing of your cities and preventing the deaths of millions of innocentr[sic] citizens of your country (and many other countries)?

“Croatians, because they actually stood for their values”

I assume you mean Ustasha (Croatian Revolutionary Movement) exterminating 75% of Croatia’s Jewish population. Those are not values that I respect….

As the older Scot said to his son, (both about to fight the English) “You see those men over there, well if you don’t kill them, they will kill you”.

Keep your moralising to yourself. War is hell.