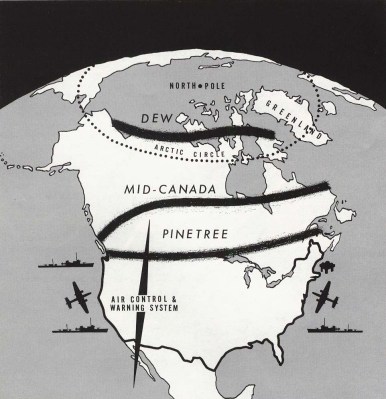

If you grew up in the middle of the Cold War, you probably remember hearing about the Distant Early Warning line between duck-and-cover drills. The United States and Canada built the DEW line radar stations throughout the Arctic to detect potential attacks from the other side of the globe.

MIT’s Lincoln Lab proposed the DEW Line in 1952, and the plan was ambitious. In order to spot bombers crossing over the Arctic circle in time, it required radar twice as powerful as the best radar of the day. It also needed communications systems that were 99 percent reliable, even in the face of terrestrial and solar weather.

In the end, there were 33 stations built from Alaska to Greenland in an astonishing 32 months. Keep in mind that these stations were located in a very inhospitable environment, where temperatures reached down to -60 °F (-51 °C). Operators kept the stations running 24/7 for 36 years, from 1957 to 1993.

System of Systems

The DEW line wasn’t the only radar early-warning system that the US and Canada had in place, only the most ambitious. The Pinetree Line was first activated in 1951. However, its simple radar was prone to jamming and couldn’t pick up things close to the ground. It was also too close to main cities along the border to offer them much protection. Even so, the 33 major stations, along with six smaller stations, did better than expected.

Mid-Canada

The Mid-Canada Line utilized bistatic radar, where the transmitter and receiver were located in different positions. The idea is that the receiver hears the transmitter along with Doppler-shifted returns from a target. That means the total travel distance of the radar beam is almost constant.

This scheme is good for inexpensively covering a wide area, but it suffers at providing exact positions. It also has trouble rejecting things like birds near either the transmitter or the receiver.

Mid-Canada first started operating in 1956, but was shut down by 1965. The reason? Speed.

The Need for Speed

In the 1940s, when Pinetree was being planned, jet aircraft were relatively new. But they made great strides, and the faster a bomber might be, the more warning you needed. While Mid-Canada was closer to the possible path of an attack, it was clear by the time it was operational that the real threat would be from ballistic missiles. Planning for the DEW Line was already underway, but it focused on fast bombers.

Moving further north was the solution. If Pinetree was relatively easy to build, building the Mid-Canada Line was more challenging due to the terrain and weather conditions. Correct topographical information was difficult to find, and paradoxically, construction had to take place during the winter when the marshland was frozen, facilitating access to many of the sites.

The DEW Line, though, was above the Arctic Circle. Building there, near the 69th parallel, would present an even bigger challenge. Working conditions were passable during the short Arctic summer, but more difficult in the harsh winter, which included a solid month of nighttime.

Prototype

The prototype station was at a weather station in Alaska’s Barter Island. There was little data on building at such high latitudes, save for the recent work done to build the Thule Air Force Base. The prototype design needed some rework in 1953, but once things were moving, the DEW Line installations managed to run for 36 years.

The typical station used prefabricated modules connected into “trains.” The modules were used as quarters, offices, equipment rooms, storage, and kitchens. Living quarters were 8′ x 12′ (2.4 m x 3.6 m). The bases were totally self-contained.

There were main stations that had a full crew and amenities like a library and other entertainment. Secondary stations typically had a chief, a cook, and a mechanic. The “gap filler” stations didn’t have any crew, but were serviced from the other stations when possible.

A main station might have two trains connected by a bridge. Smaller stations might have a single train of 25 modules. There were also garages for vehicles, warehouses, hangars, and dormitories for up to 24 personnel not housed in the main structures. While most of the stations were similar in design, the two on the Greenland ice cap were more like offshore drilling rigs, built on columns buried 100 feet into the ice.

Technology

A typical DEW line station used a 1.25 GHz radar with an average output of 400 watts, although it was rated for a maximum of 160 kW. The radar could probe from 3,000 feet out to 180 miles (300 km). Here are some details about the vacuum-tube-based technology in a 1980s booklet for newcomers to the line:

The radar system presently used was developed in the 1950’s and as such is a “tube” system which is experiencing reliability and maintainability problems. Good tubes are hard to find anymore. The operational performance is seriously affected, and support is becoming, so expensive, regardless of management improvements, that economic feasibility is only made possible by the absolute operational need for the system.

The Bell Companies played a crucial role in the development of the DEW Line. There’s an old AT&T archive video of the project that you can see below.

White Alice

Because of the challenging radio conditions above the Arctic, the stations used a system known as White Alice to communicate. Short distances used microwave links. Giant tropospheric scatter antennas provided connections beyond the horizon at 900 MHz.

The system used two antennas for reliability and also transmitted on two frequencies. For shorter hops, a 60 ft (18 m) antennas would transmit 10 kW. Longer paths used 120 ft (36 m) antennas and 50 kW. Short links used 30 ft (9 m) dishes with 1 kW of power.

Museum

Check out the DEW Line virtual museum, which tells the story from construction to the debris left to be cleaned up. There’s also an extensive collection of related videos like the one embedded below.

The DEW Line is just part of the tech history of the Cold War. Some of it was downright cloak-and-dagger.

Some stations were upgraded and incorporated into NWS.

This is adorable

Also BMEWS the ballistic missile early warning system. A half or whole hour spent watching about this in the early 60’s, boring television then but that was all that was on. It made us feel safe.

You forgot the most important part! The DEW Line system was replaced by the North Warning System, installed at the same locations. The NWS is comprised of 13 long range radar (FPS-117) and 36 short range radar (FPS-124) sites while the remaining 14 sites were “deactivated”. It was an upgrade not only in capability but also in reliability as 35 out of 36 short range sites are now unattended while the remaining 14 sites are minimally-attended. – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Warning_System

Al actually mentioned the whole transition to NWS in his draft of the post, and I pulled it b/c it interrupted the flow of the narrative. I’m to blame for that!

But thanks for the wiki. He also mentioned the https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solid_State_Phased_Array_Radar_System

My electronics instructor was a RADAR tech on these sites. He was stationed in Thule, Greenland and in Alaska. He showed us a video about the construction of one of the bases. They had to allow air to flow under them to avoid the building thawing the surrounding area and sinking.

Polar bears were a big risk, as was going outside during a storm.

He said one of the sites had a phased array that was the size of a football field layed up on it’s side.

High enough voltages that you had to strap in while in the room to raise your potential to not be shocked at a distance.

Cool stuff. He said if we ever wanted to learn about tubes and tube theory to talk to him after class…but he wasn’t going to cover it in lecture.

Didja talk to him after class?

Sadly…no.

Younger me had a habit of skipping important things like that.

Maxim used to interview/test directly out of our program too…skipped that as well.

The DEW line featured prominently in the plot of the MST3K episode: Giant Deadly Mantis.

MST3K

That is some Serious Technology on that Telecast.. !!

I think someone forgot to brush up on history… and then put on rose colored glasses… Money wasn’t wasted… it was needed at the time.

SETI pioneer Bob Stephens bought a DEW (Canada) antenna array for $1 from the government. He was so happy that day. Now, to figure out how to re-aim the array from russia to outer space… It was the early 1980’s.

I think the first problem to figure out is how to get yourself to your newly-purchased antenna or else get it to you (second option ain’t gonna happen)

Thank you for sharing this. During a trail ride our group rode atvs up to Pinetree site C7 near Parent Quebec. Its interesting to learn additional information and history of this network.

There was a Pinetree line radar base in my hometown. In spite of how useless the article makes the Pinetree line sound, the base was active until the mid-80s. I always thought they ought to have preserved at least one of the Pinetree bases as a museum, since they’re accessible enough, but they sold the housing off to some landlord who barely does maintenance, and the operations building was allowed to rot until it was finally torn down sometime after 2000.

The Barter Island Station is literally outside my window right now and still operational. It’s ran by the Air Force.

Distant Early Warning: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wrDj5XvZXX4

“War stories” by former DEW line residents:

https://www.dewlineadventures.com/stories/

My father was the Exec Officer on the construction of one of Greenland DEW Line stations. He was assigned to build the station starting from scratch, to commissioning. We have boxes of slides from photos he took on the Ice cap. The conditions were brutal, cold was fierce, and air dropping bulldozers was a challenge. A polar bear more than disrupted quarters on one occasion and artic fox were entertaining. Every inch of the foundation had to be drilled or blasted through the ice and permafrost. All the while I was in elementary school learning to duck and cover. What a time.

I was stationed on the Pinetree line during the Vietnam war. Bloody cold in the winter…

Probably a whole lot safer than the jungle. Was your dad a senator?