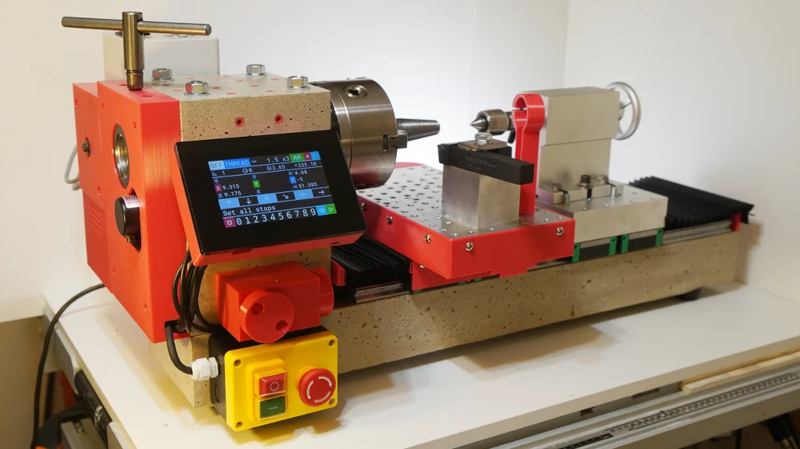

Full disclosure. If you want a lathe capable of turning metal stock, you probably should just buy one. But what fun is that? You can do like [kachurovskiy] and build one with your 3D printer. If you are chuckling, thinking you can’t make 3D printed parts sturdy enough, you aren’t exactly wrong. [Kachurovskiy’s] trick is to 3D print forms and then cast the solid parts in concrete. The result looks great, and we don’t doubt his claim that it “can surpass many comparable lathes in rigidity and features.”

Even he admits that this is a “… hard, long, and expensive project…” But all good projects are. There’s a GitHub page with more details and informative videos below. The action shots are in the last video just before the six-minute mark. Around the seven-minute mark, you can see the machine cut a conical thread. Color us impressed!

The idea of casting concrete with inserts in it is giving us a number of ideas. We haven’t done it before, but it looks like a good skill to learn. You can 3D print concrete, too. Concrete lathes are, surprisingly, not a new idea, but much harder to do without 3D-printed forms.

The elastic modulus of concrete is between 20-40 GPa which is much bendier than aluminum. It’s pretty much “cheese” compared to metals – casting the frame out of plain tin would make it more rigid. You can expect twice the amount of flex compared to aluminum, but you can easily compensate for the lack of rigidity simply by making the load bearing sections twice as wide in the direction of bending or compression. This however does mean the whole structure will weigh about twice as much as an equivalent aluminum frame.

As for the cracking problem, there was a recent Practical Engineering video about concrete structures. The video pointed out that typical concrete reaches about 75% of its nominal strength in 7 days and 90% in 28 days. If you try to clamp it down right after pouring, it will just crumble like that.

Concrete structures seem really rigid and strong to the casual observer, but they’re really not – it’s just because the typical structures are so massive that the flex becomes basically invisible to the naked eye. If you made the structure small and light enough to bend by human force, to experience the bending yourself, it’d likely just break. This lack of rigidity however isn’t a negative point for concrete: it can tolerate and conform to deformation, like ground shifting underneath a building.

And looking at the scale of that concrete casting it probably is stiffer than most similarly sized lathes, at least in the bed, slightly less convinced around the spindle and wonder how good those linear rails really are (as that will have a huge impact). But as being heavier for a machine tool is only ever a good thing – you put an excentric mass like a cam being machined on your lathe and if it isn’t really really heavy or bolted to something that is it will move on you, potentially quite fast! Might not make any difference to the machining quality if the machine is stiff but a bit light, but it will move. As I know quite well from my little watch makers lathe – its a really stiff machine for its size anyway, and even with a rather chunky cast baseplate it will happily try to walk spinning an off balance mass.

So it really doesn’t matter how much material you end up using and how massive it is, the cost, ease of production and suitability for the use environment. And there is no doubting that cast concrete is both suitable and much easier for most folks to do, especially with a 3d printed formwork than the foundry work to cast in even the usually softer lower point melting metals.

For myself I can’t see why you’d make a cast concrete machine in most places in the world, as restoring an old iron machine is likely just as much of an adventure and almost certainly gets you a better end result as those old iron machines are the product of many years of evolution to a good machine and no doubt have thousands of handy accessories made to fit so you don’t have to re-invent the wheel all the time (but obviously can if you want to). And if you really need to make your own for some reason fabricated metal structure with epoxy granite infill type concepts seems rather more flexible, likely quicker and will give a good result. But still I like this project, its interesting making use of off the shelf stuff like the linear rails etc.

That would be because most “similarly sized lathes” would be made of mostly hollow extrusions. Less material, less cross-section area, less rigidity.

If you made the same frame out of solid aluminum, it could be half as thick or even less – if so desired. However, the concrete has an advantage over aluminum in the fact that it’s not a homogeneous material. It has density differences between the cement and the gravel and sand, so it absorbs vibrations orders of magnitude better. Weight and size does matter though. Just moving them around becomes a problem, and your machine table has to support the weight.

The point of making a cast concrete lathe is that you don’t need much machining to do it. You don’t need any welding or milling or other fine metal shaping. If you can nail a few boards or glues some plastic together, you can make the forms, so it’s much more accessible to your average garage maker, and if done right it will be superior to your average hardware store or kit built lathe.

The concrete is also cheaper per unit mass, and can be poured at a slightly lower temperature.

There is a reason that we build giant building foundations out of concrete, and not out of cast aluminum. Despite the lower stiffness.

I have the opposite take. The spindle bearings have plenty of material around them in the chunky tower, which distributes the load and keeps it rigid, whereas the bed is a long thin piece that would be more susceptible to flex.

It all goes down to leverage – twice the distance doubles the bending stresses. If you’re turning a longer piece, pushing the cutting tool against the work is more likely to bend the bed than the spindle tower simply by how far away it is, but also because the tower is so much thicker in the direction of bending.

It is mostly the vertical direction on the spindle and it being concrete that makes me a little dubious – that top part is not very thick, more inline with a metal casting above the bearings, and honestly not that vast around the sides either – being square its got more mass than the usually more form fitting metal casting, but those corner part just are not all that structurally relevant, that is all on the thinnest point on the walls where the bearing go though..

Where that bed is really really massive compared to a metal bed casting. Leverage matters but so does so many other factors from how direct the force paths can be, and how much of the material is involved in dealing with any particular load. So as this is a solid brick of concrete that is huge compared to the usually quite hollow metal casting where each rail of the bed is only joined by a handful of webs.

I don’t think this is a bad machine by any stretch, but when comparing to a more normal lathe the spindle mounts walls are pretty thin at the thinnest points, so considering its made in a comparatively poor material that is the point it likely doesn’t stand up so well in comparison. Where the bed is much more substantial all round than the normal metal castings being practically a solid brick of significantly thicker dimensions all round than the similar length and bed spaced metal one – so assuming the linear rails and their mounting is up to it the bed should perform really well, I’d not be shocked if its able to perform rather better than the majority of metal castings despite the less capable material choice as its huge!

If you’re worried about the thin arch above the bearing, that is easily remedied by a sideways metal bar between the threaded rods above the bearings.

This is the source of the cracking issue as well. As the bearing tries to lift up, it spreads the top arch apart sideways and that causes the concrete to crack. Putting a rod or a bar sideways through the top would eliminate the chance. The fact that the concrete doesn’t crack in the latest iteration means that the tension forces on the arch are not that great.

Indeed, or you could thicken the side walls up so there is more material resisting it stretching open at the top, or any number of other fixes that would make it better. If its actually needed, which it might be – just because the concrete hasn’t visibly cracked doesn’t mean its not still flexible enough to make a difference, cracking is a rather complete and visible failure, but that doesn’t mean no cracks is actually a measure of good enough.

The tensile strength of concrete is pretty much 1 MPa, which is 1 N/mm^2 or the equivalent load of 10 kilos suspended from a 1 cm thick bar of concrete. It’s basically nothing. To put that into perspective, let’s say the Young’s Modulus E=20 GPa, which would mean that the proportional stretch s

s = 1 MPa / 20 GPa = 0.0005

Or 0.05% of the length of the bar. For a 100 mm long an 10 mm thick square bar, the amount it stretches before it cracks is 5 micrometers. Given a better concrete mix, that could go up to 25 micrometers, but then again the actual span of the arch at the thinnest point is not 100 mm, it’s much shorter, so that scales it back down to single micrometers.

This might have an effect on the surface quality of the part, if the bearing can move around by couple microns, but that would assume you’re doing your finishing pass or “spring pass” at full force up to the cracking point of the concrete.

Oops, I missed one zero, the actual stretch before breakage is 5e-5 which translates to some hundreds of nanometers instead of single micrometers. Point remains – the amount it can move into tension before the concrete breaks is negligible.

Oh, no I didn’t. I counted for 1 mm square bar instead of 10×10 mm bar, which throws it around the other way. Still, we’re talking about tens of microns at breakage, which is not where you should be at with the loads this lathe is experiencing.

Dude I’m not all that worried that it will move ‘hugely’ before the concrete breaks, though I’d argue in this case its probably going to be able to move a great deal further than you suggest without the crack actually being visible – the rest of the structure is still there trying to push it all closed again, and that failure isn’t likely to be anything more than a pile of hairline crack likely lost in the surface texture once it has keyed back into itself.

The worry is that even small movements and oscillations in the spindle especially with long parts and cutting tool some distance away to magnify the small movement at the spindle into a more significant one are a recipe for resonance and chatter – its not so much how far it moves, but that it can move in the wrong directions comparatively easily which I’d suggest leaves the part somewhat more able to find a resonance that causes chatter.

I’m not going to claim that is going to happen, not really done any analysis or seen enough concrete machines to form a good opinion. But given the big Iron machines are still prone to developing chatter that often appears to be a resonance not of the part itself but the whole moving assembly a more spongy spindle mount…

But then there won’t be a crack, because the material won’t be under tension.

I mean, sure, there could be a crack there, but the fact remains that it’s not opening up, which means the structure there is still under compression, which means the bearing hasn’t moved enough to cause the arch to split. If there was a crack already there, you’d see it opening up sooner with less movement, because it could do so at zero tension rather than 1 MPa. Since you don’t see one, the structure is doing its job.

I’d suggest the odds of you seeing a crack in the concrete structure are low but that doesn’t mean it isn’t there and being impactful to performance – you are talking cracks that only need to be a hair or two open on a rough surface and will only be open for a few moments, probably into the fractions of a second too small for a human to really register when the loads from the spindle are in the right direction and magnitude. I don’t expect it to be pried open and just stay open with the rest of the unbroken structure still there trying to resist that bearing’s escape for the brief moments the spindle is trying to escape vertically…

So I’d suggest you are more likely to hear the crack is there and notice the machine wants to chatter more than see it’s broken, at least for a very long time – eventually the movement might well grind the crack open enough to actually see clearly.

NB I’m not saying this spindle will have that failure, it looks like the riskiest element of the design to me but still, and even if it did break at the top that side cheek and the steel bolts would keep it intact and functional enough to be an adequate machine most likely…

If you argue that there might be cracks that do not become visible because the “rest of the material is pushing in”, you’re assuming that this is pre-stressed concrete. It actually is, but not in the direction of splitting the column at the top because the threaded rods run top to bottom, not sideways. Pushing the material down at the corners actually wedges it around the bearings and puts hoop tension around the arch against your supposed internal compression.

If the bearing moves up, it wants to stretch the hoop of concrete around the bearing, and that would put it under tension and open the split. The fact that it did crack before suggests that the structure close to the limit and would split with any significant forced movement of the bearing.

I bet this somehow hurts your intuition and you’ll keep arguing it forever until I model the whole thing and run it through FEM analysis to show you what’s actually going on.

Again, if there is a crack, but it’s not opening up because it’s under compression, the material is behaving as if it was one solid piece because the crack is not opening up. Even shearing forces along the crack would not make much of a difference, since it’s not perfectly smooth with no friction – it’s mechanically interlocked.

It’s like, if you put two springs end-to-end and compress them, for all intents and purposes they’ll act like one spring (assuming they’re otherwise identical). The only difference is when the setup is put under tension, or it is deflected sideways so much that one side switches from compression to tension, which is when the springs come apart and a spit appears.

My whole point Dude is IT IS likely opening up, just not staying that way as the rest of the structure still exists and still has that spring back to the closed position forces. Thus that crack is likely to be very hard to see as it isn’t open in most conditions.

Remember the spindle is rotating at heaps of RPM, so that even slightly off balanced mass creates that inconsistent and lateral force! Machining isn’t a fixed always static predictable forces thing, you get interrupted cuts, the lever arm of the part against the tool on the bearing changing as the tool moves position etc. So while in many cases the part or the work holding method might be the more flexible and what deflects most (which is a seriously annoying thing that comes up constantly as your boring bar or part isn’t stiff enough so its spring pass after spring pass etc). So if your spindle bearings are mounted in a broken casting…

I’m curious how performance would change if tension rods were added to put it all under compression.

Think of the materials like springs.

What would happen if you compress a light coil spring using a smaller stiffer spring that goes through the middle? If you grab hold of the loops of the softer outer spring and try to move them, would they be easier or harder to deflect while the whole spring is already compressed slightly?

You would notice that the material properties of the concrete don’t change. If it is like a linear spring, then the force F=kx where x is the distance you compress it. No matter how much you’ve already compressed the spring, the difference dF/dx=k which is the spring constant^. When you put a load on the beam, the load will simply add to the forces already within the material and deflect it by the amount of the difference.

Compressing the concrete doesn’t make it stiffer – it just makes sure it never goes under tension which would crack it. Adding tension rods can have adverse effects because the tension will itself try to bend the concrete. This is practically unavoidable, so it is instead used to take the sag out of concrete beams, and you can adjust the shape by adjusting the tension.

^(The Young’s modulus, or the elastic modulus, is a spring constant.)

The only complaint about the build itself that I have: The motor mounting bracket will creep as the motor gets warm. It’s too flimsy. This is an easy fix by bending it out of aluminum instead.

Make note that he used metal threaded inserts at the ends of the plastic inserts inside the concrete. This is very good – this anchors the screws to the concrete. Other youtubers doing concrete frames have omitted this feature. Ideally you would use a metal bar with threaded holes to give it more surface area to grab hold of the concrete and spread the load to give it more rigidity, but this is still much better than plain plastic inserts or plastic inserts with metal inserts pressed in – because again, plastic will creep and the threads or the inserts would pull out. You need the plastic around the hole to act as “grouting” to prevent the concrete from cracking, but the metal insert is what keeps the tension – the plastic won’t.

Zamak-12 would be cheaper and more rigid than tin while still having a manageable melting point.

Zamak is in a way a forgotten wonder material, relatively easy to cast as an amateur, rigid, can have fine details, and (if one can find it) not too expensive.

Zamak filled with polymer granite might be the best material for homemade machine tools. Haven’t seen that combination used in practice though.

You just have to make sure that the zamak you’re getting is the correct real thing, and not some china metal made out of casting leftovers thrown in a pot and melted together.

Yeah absolutely! Zinc need just a tiny bit of contamination to turn into an alloy from hell :/

What PSI concrete? Also, sprinkle in some graphene, you won’t need much because the project is small. I didn’t watch the video was rebar involved? If not I’d add that too.

Combining these would make a huge difference.

There are some extremely high PSI concretes available. All these combined and I think you could have something stiffer than metal.

What I don’t know about concrete, would fill a book (called “How to use concrete”). But I DO watch YouTube videos.

And those typically have – rebar. One, about pre stressed concrete, had washers on wires and the wire was stretched during casting.

Judging by all the comments, adding steel (or even aluminum) to the cast should improve rigidity.

ah, a modernized version of the Gingery lathe. nice.

Gyroid infill has just enough gaps to allow for epoxy filling to flow into it. i wonder i we can fill it with concrete using vibration table and low enough infill percentage (1-5%) to create kind of plastic rebar.

The plastic would be less rigid than the concrete, so it wouldn’t make a good “rebar”.

What you could do is fill the form up with layers and layers of chicken wire netting.

Your lathe was accepted.

as a homosapien who gifted a chance to make whatever you love, and whenever you want, you the Maxim, the toolmaker of toolmakers, brought a new standards to toolmakersionism and new horizons for the way homosapiens watching the world, earned our attention. (You homosapiens always suprise Fe). Sometimes; how to-making become more important than what to make, and all life is about how to earn not what to earn except one thing( marriage)

Keep going

As a Homo. sapiens.

It’s not a plural, don’t treat it as such.

actually, it’s Homo sapiens sapiens. Homo sapiens is an older species.

I heard that in the old days, there was a pamphlet put out by the government to guide people in how to upgrade their crummy garage lathe for precision work. I believe one of the steps was to fill the castings with concrete.

ideaf for mars habitat

What’s old is new again! From 1916:

https://flowxrgdotcom.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/new-method-of-building-lathes.pdf

I’m amused by all the people doing calculations to show how viable or non-viable they think this is.

I’m pretty sure that this was how amateurs and even some pros got started in machining back in our grandparents’ or great-grandparents’ day. They built their first lathe out of concrete. If they ever graduated to building one out of metal they used the concrete one to make it’s pieces!

Sure, some parts might have to be extra big and bulky to make up for the imperfect material. So what? That just makes it really heavy which although that’s a bad thing in most fields in metal working it’s considered a benefit! The weight helps you achieve greater precision without vibrations messing it up.

I don’t know if 3d-printing the molds is an awesome use of modern tech to get more intricate parts… Or if it’s just a case of “when the only tool you own is a hammer everything looks like a nail”, the “kids” have forgotten how easy it is to just use 2x4s, plywood , a hammer and nails.

But hey, cool build either way!

I mean sure there were some people making Gingery lathes because they had more time than money and were suckers for the DIY Hack it together vibe, But mostly, In our grandparents and great grandparents day they usually just bought an old lathe from a local machine shop when they upgraded to a new one. We still have a bridgeport mill and a hardinge lathe my great great grandfather bought in the 50s.

Going to depend on where you are in the world and the space you have no doubt. The Gingery books are great reads and on the whole at least end up producing pretty darn high spec but usually smaller scale machines it seems, and all while you never need to figure out how to lift and ship that half ton or more of cast iron. So if your ‘local’ machine shop with the old machine isn’t so local…

We moved the hardinge (~2000#) and the bridgeport (~2000#) miles from my dads place when we built out the new shop on the family farm on a flat bed trailer loaded and unloaded with a cheap gantry lift. Easy Peezy.

Our fadal 4020 weighs 12140 pounds, when we bought it we had it shipped 1100 miles from a shop in detroit that was closing down. That took a professional rigger with a healthy forklift and set us back just over $4k. We paid $8k for it so not including tooling it cost us $12k. Thats a bargain considering it was in really good condition and a new one would set you back more than twice that without delivery.

Edit, should read : We moved the hardinge (~2000#) and the bridgeport (~2000#) 300 miles

Indeed, it can be done, if the machines exist locally enough for the transport infrastructure available. But there is still the space you have problem – as most surplus machines around the world are ex-industrial and so rather larger than this or the Gingery – for me its a narrow grassy path with a sharp chicane in it and a fair step up into the small workshop – no chance at all to get that half ton+ monster to the door, even if it would fit in the space.

p.s in the UK at least there are some good supplies of used smaller scale machines having had a boom in model engineering some decades ago – so a decent Myford (etc) bench top sized lathe while not a great value proposition compared to a decent condition industrial sized machine is an option that actually roughly competes with this concrete or gingery sized lathes.

Indeed. And more importantly this DIY with concrete method while it would be very annoying to have to redesign and recast a part if something goes wrong it is something you can do at home, and do to a much larger scale than this at home even!

I can maybe find the time and space to build/buy/learn how to use a small foundry capable of casting my watch makers lathe parts, but no chance at all I’m building a foundry able to make a large benchtop machine like a Myford or bigger at home in metal. When the parts are minimums of 50Kg+ of metal each you are not doing that in metal outside of a real foundry. But the roughly comparable machine in concrete, yeah that is pretty doable.

Though for myself I really think the fabricated and epoxy granite fill type concepts are a better choice than cast concrete as a rule, especially if you don’t mind using some external help – get your local plasma/laser cutting place to cut your kit of parts and all you have to do is weld it up. But still giant Concrete machine isn’t a bad idea.

Size wise, this project appears to be more inline with a gingery lathe than a hardinge which is why I mentioned the gingery option. I dont see you using 3d printed components on an industrial scale lathe. Welding plates and pipes and filling with epoxy/granite, or saving a few bucks with concrete is definitely a better option if youre going larger than desktop, but AGAIN, I question whether youd save much money over the second hand machine shop option. HGR almost always has a dozen or so lathes in the $2-4K range that wouldnt cost you more than a grand or so to ship most anywhere in the continental US. I cant imagine there isnt a comparable equipment liquidator in europe and asia you could hit up as well.