Can a shape pass through itself? That is to say, if one had two identical solids, would it be possible to orient one such that a hole could be cut through it, allowing the other to pass through without breaking the first into separate pieces? It turns out that the answer is yes, at least for certain shapes. Recently, two friends, [Sergey Yurkevich] and [Jakob Steininger], found the first shape proven not to have this property.

Later, researchers showed this was also true of more complex shapes. This ability to pass unbroken through a copy of oneself became known as Rupert’s Property. Sometimes it’s an amazingly tight fit, but it seems to always work.

In fact, it was so difficult to find candidates for exceptions to this that it was generally understood and accepted by mathematicians that every convex polyhedron (that is, every shape with flat sides and no holes, protrusions, or indentations) would have Rupert’s property. Until one was found that did not.

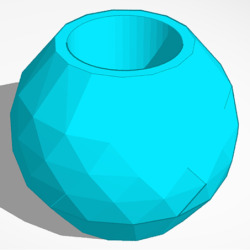

The first shape proven not to be able to pass through itself — known as the Noperthedron — is a vaguely ball-like shape, with a flat top and bottom. A fan has already added a cavity to create a 3D-printable pencil holder version of the noperthedron (shown here) if you want your own.

There are other promising candidate objects (they are rare) that may also lack Rupert’s property, but so far, this is the only proven one.

Shapes with unusual properties are interesting, and we love how tactile and visual they are. Consider Penrose tiles, a tile set that can cover any size of area without repeating. For decades, the minimum number of tile shapes needed to accomplish this was two. Recently, though, the number has dropped to one thanks to a shape known as “the hat.”

Everyone should check out Suckerpinch’s latest video on YouTube about this very topic!

+1

Is a sphere capable of passing through itself?

I suspect the open question was about polyhedra, and maybe even exclusively convex polyhedra. But IANAM…

You are right. I figured it out while reading the paper.

Answering my own question. I guess the problem is describing the object as a “shape” (per HaD), rather than “polyhedron” (the paper).

While a a sphere cannot pass through itself, a sphere is also not polyhedron, and does not count in this case.

Here’s a link to the paper, which was useful in answering this: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2112.13754

HaD should probably include something about that, since “identical solids” and “shape” doesn’t accurately describe what the paper is really about.

Sorry for the pedanticism.

No need to apologize – you are technically correct, which as we all know is the best kind of correct!

The paper you linked to is interesting and good background but I think the one claiming to prove that a polyhedron is nonRupert is this one

https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.18475v1

They slightly generalize the idea of being rupert in the abstract also but very quickly only talk about polyhedron. Probably the source of the confusion in this summary.

I had the same question about the sphere as you.

Ah, thanks! I was focused on the sphere non-Repert-ness and I didn’t notice I was reading the wrong paper.

I had the same thought but my guess is that’s why it got limited to polyhedra.

Which makes me think that polyhedra that approximate spheres would be a good place to look.

Also came here looking for this.

The article should say that this is specific to polyhedra not ‘shapes’.

How would it?

Despite what all the self-funded nerds might say, this is not a real shape. If it is, then the question itself is pointless. Okay, so you have a reversible manifold? Then what?

It’s unnecessarily confusing but the actual shape does not have the hole in the middle. That is the pencil holder version of the shape. It is the multifaceted sides with flat top and bottom.

Nevertheless interesting! ;)

I see this as the Flatland problem. Even though the hole through the three-dimensional object has depth, it is uniform and effectively a two-dimensional plane as far as the inserted object is concerned for the purposes of traversal.

There is no way this is even a thing. It can think of at least 3 shapes in under a minute that can do this. Surly we r smarter than this.

And those shapes are…?

The closer the polyhedron is to being a sphere, the less likely it is to have Rupert’s Property. Now I just need to spend the next 30 years working on the math to prove it…

Reminds me of the quarterfoil just to say plainly, in my opinion when you draw a quarterfoil in just lines you can intersect the lines to make shapes likes these with no effort. I like to call it gods eye.

Man hole cover