A Crookes radiometer, despite what many explanations claim, does not work because of radiation pressure. When light strikes the vanes inside the near-vacuum chamber, it heats the vanes, which then impart some extra energy to gas molecules bouncing off of them, causing the vanes to be pushed in the opposite direction. On the other hand, however, it is possible to build a radiometer that spins because of radiation pressure differences, but it’s easier to use acoustic radiation than light.

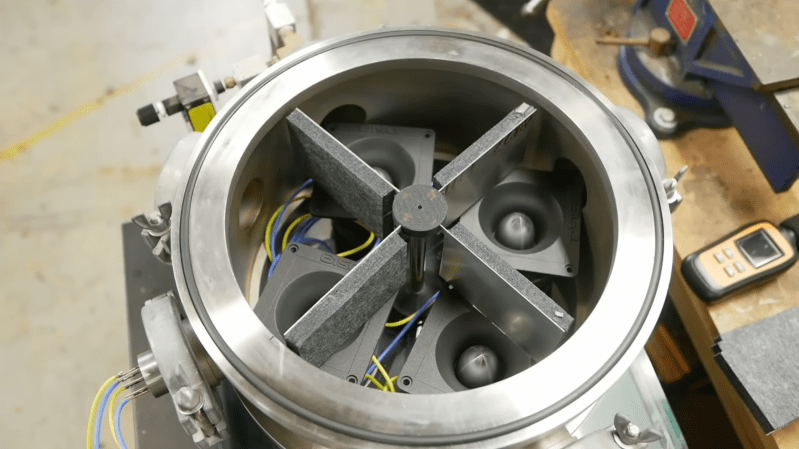

[Ben Krasnow] built two sets of vanes out of laser-cut aluminium with sound-absorbing foam attached to one side, and mounted the vanes around a jewel bearing taken from an analog voltmeter. He positioned the rotor above four speakers in an acoustically well-sealed chamber, then played 130-decibel white noise on the speakers. The aluminium side of the vanes, which reflected more sound, experienced more pressure than the foam side, causing them to spin. [Ben] tested both sets of vanes, which had the foam mounted on opposite sides, and they spun in opposite directions, which suggests that the pressure difference really was causing them to spin, and not some acoustic streaming effect.

The process of creating such loud sounds burned out a number of speakers, so to prevent this, [Ben] monitored the temperature of a speaker coil at varying amounts of power. He realized that the resistance of the coil increased as it heated up, so by measuring its resistance, he could calculate the coil’s temperature and keep it from getting too hot. [Ben] also tested the radiometer’s performance when the chamber contained other gasses, including hydrogen, helium, carbon dioxide, and sulfur hexafluoride, but none worked as well as air did. It’s a bit counterintuitive that none of these widely-varying gasses worked better than air did, but it makes sense when one considers that speakers are designed to efficiently transfer energy to air.

It’s far from an efficient way to convert electrical power into motion, but we’ve also seen several engines powered by acoustic resonance. If you’d like to hear more about the original Crookes radiometers, [Ben]’s also explained those before.

Acoustic pressure is a traceable, gold standard method of measuring acoustic power. It’s been done for at least the last half century.

If you’re fortunate enough to be fluent in SI it falls right out in the units.

It’s even a standard: ISO 3745 Determination of sound power levels and sound energy levels of noise sources using sound pressure.

Ben should have known this from his previous work.

It’s trivial to measure even milliwatt levels of acoustic power with the appropriate force (pressure) sensor. No need to cook voice coils to demo this.

Yeah but that’s not as fun.

Pressure is not the same as power.

Acoustic power = intensity integrated over a surface. For the total power, this surface should envelope the radiator.

Intensity = particle velocity * pressure.

I think that you can infer power from pressure, but only in the far field (which is what the ISO standard assumes). If the radiator can be approximated as a point source, you know the relationship between intensity and pressure. In the near field this isn’t true.

Work it through. Include the speed of sound. You’ll see it works perfectly.

It’s exactly the same relation as the radiation force from light.

Pressure is power density (divided by speed of sound, or light).

Force is total power (divided by speed of sound, or light).

It’s a convenient way to measure the power from ultrasound transducers, for example.

This is nonsense. Local particle velocity is not equal to the speed of sound.

This is the reason why acoustic intensity probes exist.

Nobody mentioned local particle velocity.

And how do you suppose acoustic intensity probes get calibrated?

Just because you don’t understand it does not negate the fact that it is an industry standard technique in acoustic power measurement, and has been for decades.

Sure several standards only use sound pressure. But these build on the far field assumption of a spherical wave front. Which is why they also describe how far away you should measure, and why the measurements are ideally performed in an anechoic chamber or OATS.

If the acoustic field is more complex (for example in a room with a few reflections, or close to a complex radiator), sound pressure alone is not enough to accurately determine sound power. In that scenario intensity measurements are required (see ISO 9614).

In your example of ultrasound transducers the free field assumption often makes sense because of the very short wavelengths involved. But that does not make it generally true for all frequencies.

Fun fact, this effect of measuring the speaker coil temperature and controlling power accordingly is how modern macbook speakers get such loud sound out of such tiny drivers. It’s also why Asahi linux now requires a userspace daemon (speakersafetyd) running all the time to continually calculate the temperature of the coils and feed information back to the kernel. (there’s a safety interlock that prevents sound from working above a massively cut-down level if the daemon isn’t running)

If this rig works like Ben postulates, then he has just invented a propellantless “reactionless” drive rocket.

Consider the case of a single sealed cavity, with one perfectly absorbing wall facing one perfectly reflecting wall, and the cavity filled with sound. One unit of sound being absorbed by the absorber will yield one unit of force in that direction. One unit of sound bouncing off the reflector will yield, as Ben correctly says, two units of force. But that reflected sound will then get absorbed by the opposite absorbing wall, adding another unit of force it produces.

The net result is two units of force, in opposite directions, cancelling out. You’ll actually get zero net force.

It’s the same as filling an airtight box with pressurized air: In a closed box the acoustic force presses equally on all surfaces. Only by letting it out a hole in one wall will you get a net force to push the box.

And what will happen to the sound that bounces off the smooth side? It will travel and be absorbed by the other, netting zero momentum.

Exactly the same as if you had photons.

Did you even read past the first sentence before reflexively blurting?

I gather that Ben was at that NASA supercomputer center tour, and they showed that they use a special paint for windtunnels that is pressure sensitive and shows the pressure visually.

That made me wonder if that would work with Ben’s device, since (very loud in his case) audio is just pressure.

Problem though is that that paint is only active a short time and then has to be replaced the person at NASA said. Few hours I think. So that’s a bummer.

I wonder though if Ben will investigate that paint and might manage to make his own, it’s the kind of thing he would do after all, and it would be interesting to watch and hear about.