Continuing his reverse-engineering of the Intel 8087, [Ken Shirriff] covers the conditional tests that are implemented in the microcode of this floating point processing unit (FPU). This microcode contains the details on how to perform the many types of specialized instructions, like cos and arctan, all of which decode into many microcode ops. These micro ops are executed by the microcode engine, which [Ken] will cover in more detail in an upcoming article, but which is effectively its own CPU.

Conditional instructions are implemented in hardware, integrating the states of various functional blocks across the die, ranging from the instruction decoder to a register. Here, the evaluation is performed as close as possible to the source of said parameter to save on wiring.

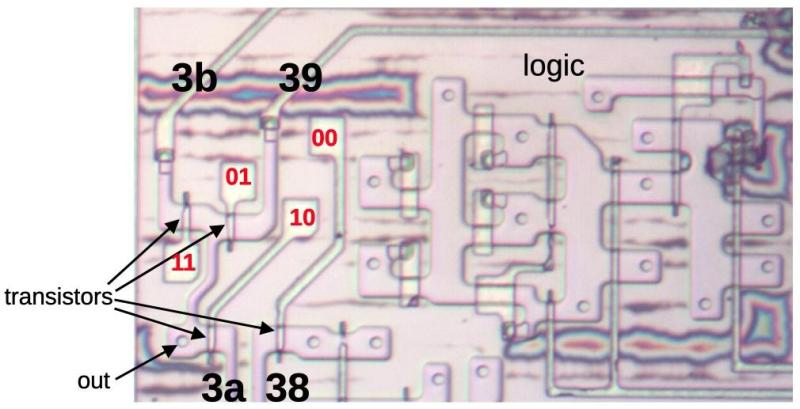

Implementing this circuitry are multiplexers, with an example shown in the top die shot image. Depending on the local conditions, any of four pass transistors is energized, passing through that input. Not shown in the die shot image are the inverters or buffers that are required with the use of pass transistors to amplify the signal, since pass transistors do not provide that feature.

Despite how firmly obsolete the 8087 is today, it still provides an amazing learning opportunity for anyone interested in ASIC design, which is why it’s so great that [Ken] and his fellow reverse-engineering enthusiasts keep plugging away at recovering all this knowledge.

What Ken and fellows do is great. What would even be greater is companies actually releasing this documentation and knowledge when parts become obsolete. That would benefit the entire world.

Unless they lost it. Not unusual at all.

The 8087 really is fascinating!

Here’s an interview you might be interested in.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L-QVgbdt_qg

I am reminded of the i486 with its integrated floating-point HW versus the 68030 without it. I believe that was a contributing factor in industry movement away from Motorola toward Intel.

This study shows area being dedicated to control structures, effectively a micro-CPU. So Intel’s decision to integrate HW floating point likely did not increase area requirements of an integrated CPU as much as one would assume. They took a gamble on adding all that hardware to the 486. I always thought they won on planned improvements to yield, but this 8087 study shows that they likely also saw the cost/area advantage, and system implementation cost, of a single-chip CPU core.

Interesting series of articles…

I’d say by the time of the i486 the battle was already over and Intel had won hands down.

In the times of the XT and AT Motorola and others still had a chance, Motorola even had the better processors. But from the 80386 on Intel was ahead. Also DOS and Windows were becoming industry standards.

I think it’s..a bit complicated.

Also since different users had different needs, maybe.

Firstly, MS-DOS (and compatible DOSes such as DOS Plus) were a thing by mid-80s, already.

By ca. 1985 CP/M was near dead and MS-DOS took its place.

Programs such as Turbo Pascal 3 were the last big CP/M and CP/M-86 applications.

By mid-80s, IBM PC platform+DOS also pushed the “MS-DOS Compatibles” out of the race (PCs that ran DOS on non-XT architecture).

By mid-80s, the Tandy 1000 was popular at US homes, for both DOS games and applications.

In Europe, the Amstrad/Schneider PC1512 took a similar role at homes.

The Olivetti PC1 in Italy, too, maybe.

So by 1985, when both the 68000-based Atari ST and Amiga came out, MS-DOS already was “a thing”.

By that time, DOS Plus 1.2 was out, too and ran on British BBC Master 512 or the PC1512..

That’s also why both Atari and Commodore had demoed PC emulators on their 68k machines or had built PC compatibles.

Amiga had Transformer application, for example.

The Atari ST platform had PC-Ditto (third-party) by ca. 1986.

Both companies also made IBM PC compatible PCs..

Commodore PC-10 or Atari PC1, both ca. 1985/1986.

By 1987, when Amiga 500/2000 became mainstream Amigas, the PC platform already had Super EGA cards doing 800×600 16c for a whole year!

In 1987, VGA came out as a cheap successor to EGA.

The first VGA clones appeared in late 1987, such as the ATI VIP.

By early 1988, many many VGA cards such as ATI VGA Wonder or Paradise PVGA came out.

And they weren’t just plain VGA, but rather Super VGA from the start – they could do things such as 640×400 256c or 800×600 16c or 1024×768 4c.

And they shipped with drivers for applications such as GEM, AutoSketch/AutoCAD, Ventura Publisher, WordPerfect or Windows 2 (plain, 286 and 386 edition).

(By 1989, VESA VBE was introduced and provided a standardized, vendor independent 800×600 16 colors mode [VBE mode 6Ah, later also duplicated as 102h].

The first VESA drivers [DOS TSRs] were shipped with the driver/utility disks of VGA cards.)

By 1988, the fast 80286 PCs with 10 MHz and up were becoming the norm.

Many featured EGA or VGA as on-board graphics, even.

16 and 20 MHz 386 PCs were becoming a favorite among developers and power users.

DESQView/386, Xenix 386, Windows/386, OS/2..

Intel released 386SX, a low-cost 386, in 1988 too.

At Atari, the Atari ETS was mentioned in 1986, it was meant to be released in 1987. The model had an 68020, but it wasn’t sold.

A year later in 1988, the Atari TT with an 68020 was demoed,

which finally sold from ca. 1990 onwards with an 68030 instead.

https://www.atarimuseum.de/tt030.htm#est

The whole systems with 68020, 68030, 68040 etc were three (!) years to late.

If 68030 systems appeared in 1987, they would have had a chance.

Remember, the Commodore Amiga 2000 from 1987 had a CPU upgrade slot for a reason!

It was meant to take an 68030 upgrade card (or 68020 at least).

The only platform that comes to mind that used later 68k processors at about the right time was the Macintosh.

68020 by 1987 with Macintosh II, 68030 by 1989 with Mac SE/30, 68040 by early 90s (many models).

But Macintosh platform wasn’t exactly mainstream to begin with, maybe.

At least not where I live. Here in Germany, Atari STs with SM124 mono monitor took the role of Macintoshs up until early 90s.

The users also ran Mac emulators, if needed.

(Some applications were not available for TOS/GEM but only for System).

By ca. 1988-1992, some professionals used 19″ mono CRTs on their STs, in 1280×960 resolution (640×480 resolution doubled by two).

In early 90s, the widely available Tseng ET-4000 ISA card was used in Atari Mega STs via an adaptor board, too, I think.

NVDI had support for it, so it could be used on GEM Desktop for well-behaved GEM applications.

Power users with their Ataris tried to overclock their 68000 machines early on or installed 68020/68030 upgrade boards, such as PAK68.

Because an 8 Mhz 68000 just didn’t cut it. 16 or 32 MHz clock speeds were sought after by late 80s.

The 68010 also was used as simple drop-in replacement, comparable to how PC/XT users had dropped in an NEC V20/V30..

In both cases, the performance was slightly increased.

The 68010 had a little buffer and virtual memory support,

while the NECs were quicker and had added some later x86 instructions found on 80286.

That’s just a very crude summary, of course. And maybe a bit biased, too.

But the point is, the 68030 should have been around same time the 386 had gained traction.

And not just by early 90s with the many CPU upgrade boards sold by third-party vendors.

By early 90s, Atari left PC business and made game consoles again (Atari Jaguar, Lynx etc).

By mid-90s Atari ST/TT users started to run MagiC on high-performance emulators instead (for Mac, PC) in order to continue to use their favorite 68k-based GEM applications (Calamus etc).

Merely the MIDI folks kept using the real vintage hardware in order to run Cubase etc, I think.

And Commodore? Where I live, the last hurray was ca. 1994,

when the last games had gotten an Amiga port.

But by 1993 it already got been superseded, strictly speaking.

1993 was the time that “talkie” versions of certain DOS games first came out on CD-ROM.

It was the time that DOS4GW extender games became a thing.

They were using 386 Protected-Mode and needed a 386/486 CPU.

On Mac side of things, the 68040 was the standard by 1993/1994,

with the Power PC processor (601) already taking the lead.

That’s why the 680EC40 emulator was baked into Mac firmware by the time the first Power Macs appeared.

Meanwhile in industry, the Amiga platform was still relevant for running D-Paint and for video editing (some DVRs ran on custom Amiga hardware too).

Or to power some arcade cabs or virtual reality systems (some based on Amiga 3000 and 68030 CPUs).

Heck, even the 68010 if offered as an official upgrade in the 80s would have been an improvement over plain old 68000 (it’s from the 70s!).

The little buffer indirectly helped in situations such as 3D rendering, because it let the 68k repeat certain instructions without accessing RAM each time.

It also allowed virtual memory (albeit with some little help of an MMU maybe),

so TOS and AmigaOS could have had used real multitasking using virtualized memory (applications could have run in VMs within their own, isolated address space each; like on Win NT or OS/2).

Again, it’s just a crude summary, to give an impression that might be unpopular among the hobby users.

Long story short, the 68k platform progressed too slowly, I think.

If the 68060 would have been in wide use before or same time as the Pentium (1993) was released, it might still have changed something.

Don’t forget the Apple Quadras of the early 90s. It was mainly used in DTP and media type applications, because the platform as a whole ran rings around their Intel-based counterparts. I do believe that this was the last time, that the 68k had a chance, if Apple just wasn’t such a closed-off ecosystem (which made it expensive). I do believe it was the openness (intentional or not) and price advantage that gave the PC platform the edge…not technical superiority.

The expense didn’t just come from the walled garden, they didn’t sell enough to meet the economies of scale necessary to reduce the price.

Motorola were not ready to provide a CPU for the 5150 and it turned out to be the most important microcomputer ever made. Intel and Microsoft made sure they were along for the ride.

Speaking of the 8087 and the 80386..

To my experience, an 8088+8087 sometimes perfomed nearly as good as an 80386 without any NPU.

That’s how impressive the little 8087 really was!

In DOS applications such as AutoCAD or AutoSketch,

the x87 support made a difference like day and night. No exaggeration.

(For applications such as Autodesk 3D Studio it was a requirement.)

That’s why good 8087 emulators such as Franke.387 (for 386) were so useful.

Or why math co-processors sold so well and had so many third-party vendors (esp. 287/387 models for fast ATs).

Or why the Intel RapidCAD was such an improvement to 386 platform.

It used same 486 design that gives the internal math co-processor access to the quick on-chip cache!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RapidCAD

PS: The Waiteks shouldn’t be forgotten, either.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weitek

Co-processors are such a fascinating topic! ^_^

Some added SIMD like features years before the advent of MMX or SSE.

https://www.cpu-collection.de/info/copro16a.txt

The i80486 was contemporary to the m68040 (1989 and 1990), not the m68030. Both the i80486 and m68040 had integrated FPUs.

CPUs with integrated FPUs didn’t save on die space because the micro-CPU executing FPU microcode isn’t the same as the one executing CPU microcode. That wouldn’t make sense unless there wasn’t any desire to pipeline FPU and CPU instructions.

Yes, but there’s a difference, maybe.

The 80486 had a feature complete FPU that included all features of the prior x87 units.

The 68040 FPU was a little bit cut-down compared to 68020/68030 plus Motorola 68881 or 68882.

“The FPU in the 68040 was incapable of IEEE transcendental functions,

which had been supported by both the 68881 and 68882

and were used by the popular fractal generating software of the time and little else.

The Motorola floating-point support package (FPSP) emulated these instructions in software under interrupt.

As this was an exception handler, heavy use of the transcendental functions caused severe performance penalties.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motorola_68040#Design

But to be fair, the 80486 math co-processor wasn’t perfect, either.

Some late math-coprocessors for 80387 socket had matrix features such as 4×4 or an optional memory mapped access (in native mode).

These sophsticated features never made it into intel’s 80486 or the Pentium,

but remained limited to 80386 mainboards who could host a dedicated, third-party math-co.

There was Amiga software that patched the executable code in ram so there was only one exception per instruction, for each time you ran the application.

This largely removed the penalty

The Motorola 680×0 market was basically Macs + Home computers + high-end workstations. It’s fairer to say that the home computers didn’t move from 680×0’s to i486’s until Commodore & Atari went bust and the high-end moved to RISC, because it was a better architecture and then Intel copied RISC insights in order to regain ground.

In either case, it wasn’t the FPU, nor the fact it was integrated. By the time the i486 was on the market (in late 1989), RISC workstations such as the Sun SparcStation 1 were already on the market and able to show a higher performance in both integer and much higher performance in floating point than the i486 even for comparable prices (early 486 PCs cost in the $10K range too). Thus, they were not a primary challenge at that end. Moreover, 486 PCs lacked mature 32-bit OS’s for the high-end too and for that reason even Motorola 68030 workstations were able to sell in reasonable numbers into the 1990s (e.g. the revolutionary NeXT Computer).

I think you make a good point about FPU integration not increasing the size of the CPU as much as one might imagine. Perhaps Intel could have therefore done that a generation earlier, by dumping the segmented architecture when creating the 386 leaving only paged support (and perhaps restricted to 32MB physical/128MB virtual, since the i386 was obsolete by the time PCs needed more than that and hardly anything used segmented VM properly) and added FPU microcode and x87 registers :-) .

Writing my own reply to this. So, if we start with this Ken Shirriff post:

https://www.righto.com/2025/05/intel-386-register-circuitry.html

We can make simple guesses about what would be involved. The Register block is about the same size as the Segment descriptor cache, so we can replace the latter with FPU regs. The Segment unit could be replaced by FPU microcode. The paging unit and page cache could probably be reduced if we wanted 32MB/128MB since that involves just 13-bits for translation and 15-bits for tags (upper bits can be forced to be either 11111 or 00000). So, if a TLB is just 32-bit the other 4 bits could be used for the translation status: (user/super { other levels for the future}, [not-present/execute-only/RO/RW]).

But basically, it’d fit.

Backward compatibility with existing applications is the only reason that the 386 was successful. Intel can’t even drop 16 and 32 bit mode from their latest cpus.

Agreed. And arguably, assembly-level CPU and CP/M backward compatibility is the primary reason the 8086 was successful and the reason why Intel can’t drop 16-bit and 32-bit modes.

The 80386 also was considered a “mainframe on a chip” once in the 1980s.

What the 80386 made so interesting to existing users was V86 and the enhanced MMU.

And the much higher performance and 32-Bit memory i/o, of course!

The 80386 could simulate bank-switching for EMS, but also trap i/o access, DMA and other things (later used by EMM386 and QEMM in the 90s).

The MMU also got a paging unit, so “swap to disk” worked basically in hardware.

In the late 80s, Xenix 386, Windows/386 and AutoCAD 386 made good use of the 386.

On an older 80286, virtual memory and segmentation were available already. Its MMU was a precursor to the 386 MMU.

Besides Concurrent DOS 286 (or DOS XM?), OS/2 1.3 basically was the most sophisticated piece of software to support 286 features.

Such as using ring levels 0, 2 and 3 and segmentation.

Unlike Windows 3.x, it also supported virtual memory (swap file) on an 80286.

And that’s why it was so stable, I think. 16-Bit OS/2 didn’t take the easy route like 32-Bit OSes did.

There’s another layer of security based on “memory potection based on segmentation”, for example.

Segments used in 286 Protected Mode can be marked as executable or data (Real Mode didn’t have that).

Modern OSes such as Windows NT (Win XP) which were using a “flat memory model” had to wait until advent of NX-Bit and DEP that they got that feature back.

(The 386 MMU’s segmentation unit is still active in “flat mode” model used in 386 Protected Mode,

but there’s merely one big 4GB segment remaining so it has nothing to do.

A 32-Bit OS with segmented memory model would have been able to handle 64 TB of virtual memory on a 386.)

But sure, backwards compatibility was an important feature of the 386!

It wasn’t the only factor, though. Just like new 32-Bit registers (EAX, EBX etc) and the 386 instructions set weren’t most important thing.

Most known 386 applications such as Windows/386 were still mostly 16-Bit, except for Unices such as Xenix 386.

It rather was the enhanced MMU that stood out, I would say.

DESQView 386 or DOS like OSes such as PC-MOS/386 allowed an Unix experience on a 386 PC.

A single PC could be used for running multiple programs simultanously, with each program having those famous 640KB for its own purpose, running preemptively.

On an 80286 without extra hardware, merely Concurrent DOS 286 was able to multitask on a comparable level, I assume.

But only if the DOS applications behaved in a good fashion.

Concurrent DOS used a lot of 286 tricks to make thst happen.

On an even older PC/XT, an EMS board with backfilling feature was needed for a similar experience.

Here, the EMS board got most of the motherboard RAM (only 64KB or so left for booting) and then the EMS board acted like an MMU to the motherboard!

Memory boards such as AST Rampage or Intel Aboveboard were such early EMS boards.

For DMA and backfilling, EEMS or LIM4 capable boards were required, I vaguely remember.

By contrast, EMS 3.2 based memory boards and 286 chipsets featuring EMS were too limited.

They merely had a fixed page frame for 4x 16 KB pages (64 KB).

DESQView was one of the extensions who could use that backfilling feature, I think.

Given the hardware, it could swap whole conventional memory in/out, along with full blown DOS applications in it (a few hundred KBs).

That’s why QEMM came to be, originally.

It used to be a an companion application to make DESQView run on 386 PCs without dedicated EMS memory boards.

The 386 MMU was very good at emulation, in short.

Even without native 8086 instruction compatibility the 80386 would have been successful.

Because the powerful MMU and the well performing 386 core could have trapped illegal instructions and handle them in software.

The performance of an emulated 8086 core wouldn’t been much worse than emulating an Z80 on an 80286 based AT (which Z80MU and other CP/M emulators did well in late 80s).

Speaking of the 80286, the lesser known EMU386 utility does trap missing 386 instructions (just Real Mode) on an older 286 and handles them in software as an exception.

Performance isn’t that bad, either. It’s not exactly same thing as true emulation of a whole 8086 in software, I must admit. :)

PS: Sorry for the long comment! I hope you don’t mind!

It surely has some flaws but I hope it tells good enough how everything works together.

Because I think the topic is very interesting, also because 8086, 80286 and 80386 have had so different design philosophies, originally.

The 8086 allowed easier porting of 8080 code,

the 80286 was meant as a processor in databases, controllers or PBXes,

the 80386 was the aforementioned mainframe on a chip..