An important aspect in software engineering is the ability to distinguish between premature, unnecessary, and necessary optimizations. A strong case can be made that the initial design benefits massively from optimizations that prevent well-known issues later on, while unnecessary optimizations are those simply do not make any significant difference either way. Meanwhile ‘premature’ optimizations are harder to define, with Knuth’s often quoted-out-of-context statement about these being ‘the root of all evil’ causing significant confusion.

We can find Donald Knuth’s full quote deep in the 1974 article Structured Programming with go to Statements, which at the time was a contentious optimization topic. On page 268, along with the cited quote, we see that it’s a reference to making presumed optimizations without understanding their effect, and without a clear picture of which parts of the program really take up most processing time. Definitely sound advice.

And unlike back in the 1970s we have today many easy ways to analyze application performance and to quantize bottlenecks. This makes it rather inexcusable to spend more time today vilifying the goto statement than to optimize one’s code with simple techniques like zero-copy and binary message formats.

Got To Go Fast

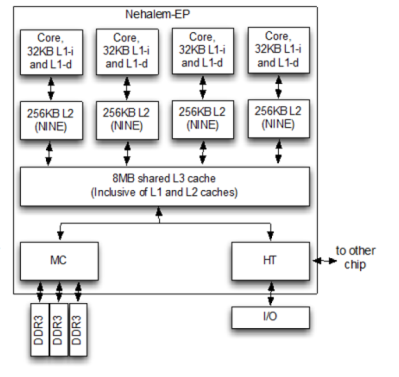

There’s a big difference between having a conceptual picture of how one’s code interacts with the hardware and having an in-depth understanding. While the basic concept of more lines of code (LoC) translating into more RAM, CPU, and disk resources used is technically true much of the time, the real challenge lies in understanding how individual CPU cores are scheduled by the OS, how core cache synchronization works, and the impact that the L2 and L3 cache have.

Another major challenge is that of simply moving data around between system RAM, caches and registers, which seems obvious at face value, but the impact of certain decisions can have big implications. For example, passing a pointer to a memory address instead of the entire string, and performing aligned memory accesses instead of unaligned can take more or less time. This latter topic is especially relevant on x86, as this ISA allows unaligned memory access with a major performance penalty, while ARM will hard fault the application at the merest misaligned twitch.

I came across a range of these issues while implementing my remote procedure call library NymphRPC. Initially I used a simple and easy to parse binary message format, but saddled it with a naïve parser implementation that involved massive copying of strings, as this was the zero-planning-needed, smooth-brained, ‘safe’ choice. In hindsight this was a design failure with a major necessary optimization omitted that would require major refactoring later.

In this article I’d like to highlight both the benefits of simple binary formats as well as how simple it is to implement a zero-copy parser that omits copying of message data during parsing, while also avoiding memory alignment issues when message data is requested and copied to a return value.

KISS

Perhaps the biggest advantage of binary message formats is that they’re very simple, very small, and extremely low in calories. In the case of NymphRPC its message format features a standard header, a message-specific body, and a terminator. For a simple NymphRPC message call for example we would see something like:

uint32 Signature: DRGN (0x4452474e) uint32 Total message bytes following this field. uint8 Protocol version (0x00). uint32 Method ID: identifier of the remote function. uint32 Flags (see _Flags_ section). uint64 Message ID. Simple incrementing global counter. <..> Serialised values. uint8 Message end. None type (0x01).

The very first value is a 32-bit unsigned integer that when interpreted as characters identifies this as a valid NymphRPC message. (‘DRGN’, because dragonfly nymph.) This is followed by another uint32 that contains the number of bytes that follow in the message. We’re now eight bytes in and we already have done basic validation and know what size buffer to allocate.

Serializing the values is done similarly, with an 8-bit type code followed by the byte(s) that contain the value. This is both easy to parse without complex validation like XML or JSON, and about as light-weight as one can make a format without adding something like compression.

Only If Needed

When we receive the message bytes on the network socket, we read it into a buffer. Because the second 32-bit value which we read earlier contained the message size, we can make sure to allocate a buffer that’s large enough to fit the rest of the message’s bytes. The big change with zero-copy parsing commences after this, where the naïve approach is to copy the entire byte buffer into e.g. a std::string for subsequent substring parsing.

Instead of such a blunt method, the byte buffer is parsed in-place with the use of a moving index pointer into the buffer. The two key methods involved with the parsing can be found in nymph_message.cpp and nymph_types.cpp, with the former providing the NymphMessage constructor and the basic message parser. After parsing the header, the NymphType class provides a parseValue() function that takes a value type code, a reference to the byte buffer and the current index. This function is called until the terminating NYMPH_TYPE_NONE is found, or some error occurs.

Looking at parseValue() in more detail, we can see two things of note: the first is that we are absolutely copying certain data despite the ‘zero-copy’ claim, and the liberal use of memcpy() instead of basic assignment statements. The first item is easy to explain: the difference between either copying the memory address or the value of a simple integer/floating point type is so minimal that we trip head-first into the same ‘premature optimization’ thing that Mr. Knuth complained about back in 1974.

Ergo we just copy the value and don’t break our pretty little heads about whether doing the same thing in a more convoluted way would net us a few percent performance improvement or loss. This is different with non-trivial types, such as strings. These are simply a char* pointer into the byte buffer, leaving the string’s bytes in peace and quiet until the application demands either that same character pointer via the API or calls the convenience function that assembles a readily-packaged std::string.

Memcpy Is Love

Although demonizing ‘doing things the C way’ appears to be a popular pastime, if you want to write code that works with the hardware instead of against it, you really want to be able to write some highly performative C code and fully understand it. When I had written the first zero-copy implementation of NymphRPC and had also written up what I thought was a solid article on how well optimized the project now was, I had no idea that I had a “fun” surprise waiting for me.

As I happily tried running the new code on a Raspberry Pi SBC after doing the benchmarking for the article on an x86 system, the first thing it did was give me a hard fault message in the shell along with a strongly disapproving glare from the ARM CPU. As it turns out, doing a direct assignment like this is bound to get you into trouble:

methodId = *((uint32_t*) (binmsg + index));

This line casts the current index into the byte buffer as a uint32_t type before dereferencing it and assigning the value to the variable. When you’re using e.g. std::string the alignment issues sort themselves out somewhere within the depths of the STL, but with direct memory access like this you’re at the mercy of the underlying platform. Which is a shame, because platforms like ARM do not know the word ‘mercy’.

Fortunately this is easy to fix:

memcpy(&methodId, (binmsg + index), 4);

Instead of juggling pointers ourselves, we simply tell memcpy what the target address is, where it should copy from and how many bytes are to be copied. Among all the other complex scenarios that this function has to cope with, doing aligned memory address access for reading and writing is probably among its least complex requirements.

Hindsight

Looking back on the NymphRPC project so far, it’s clear that some necessary optimizations that ought to have been there from the very beginning weren’t there. At least as far as unnecessary and premature optimizations go, I do feel that I have successfully dodged these, but since these days we’re still having annual flamewars about the merits of using goto I very much doubt that we will reach consensus here.

What is clear from the benchmarking that I have done on NymphRPC before and after this major refactoring is that zero-copy makes a massive difference, with especially operations involving larger data (string) chunks becoming multiple times faster, with many milliseconds shaved off and the Callgrind tool of Valgrind no longer listing __memcpy_avx_unaligned_erms as the biggest headache due to std::string abuse.

Perhaps the most important lesson from optimizing a library like NymphRPC is that aside from it being both frustrating and fun, it’s also a humbling experience that makes it clear that even as a purported senior developer there’s always more to learn. Even if putting yourself out there with a new experience like porting a lock-free ring buffer to a language like Ada and getting corrected by others stings a little.

After all, we are here to write performant software that’s easy to maintain and have fun while doing it, with sharing optimization tips and other tricks just being part of the experience.

A few things about your structure…

1) A memcpy of 4 bytes isn’t even calling memcpy. The compiler sees your inefficient request and turns it into reasonable code to do the job. If instead, it did what you had asked (or had to because you passed the length in a variable), that call to memcpy would have been quite a bit more expensive than just dealing with unaligned pointers yourself.

2) You’ve created unnecessary pain for yourself with that structure design. If instead, you had rolled the protocol version into N bits of the flags field, you wouldn’t have to deal with unaligned pointers at all.

This is why memcpy is good. It’ll do the right thing without you having to care what the right thing is, and it’ll do it fast. If you think “memcpy is simply a loop and I can do better”, you’re setting yourself up for failure, as it’s a semantic instruction to copy memory, not a mechanical one.

And the compiler optimizer is better than you. Even if the memcpy implementation is crude, it can still recognize, collapse and inline the optimal code for you, as long as you don’t explicitly force it to do things your way.

memcpy is usually quite optimized, but I see too often people attribute magical properties to compilers. For example:

int len = some_length_variable; // this is set to 4 somewhere else

memcpy(dst, src, len);

In this case, the use of memcpy is a grotesque waste of CPU cycles and will result in code that takes 100 times longer to execute than more efficient means. The compiler won’t second guess variable contents and can’t see that the value will be 4 at run time. When I see memcpy(a, b, 4) it tells me that the author doesn’t know how C/C++ works.

” while unnecessary optimizations are those simply do not make any significant difference either way.”

In typical usage, I would understand “optimization” to mean “modifying the code to improve some measurable aspect of its performance.” If you changed the the code and no measurable improvement occurs, then by definition, you didn’t “optimize” it. Either the code is already at peak and no incremental improvement is left to be had, or you changed code not properly associated with the intended improvement. Either way, this devolves to the status of a change made for the sake of change.

It seems “optimization” here doesn’t mean “improve aspect X of the code’s performance” but instead means, “selecting compiler options that promise optimizations, but in many instances won’t/can’t deliver them.”

It might be useful, then, to first define what you mean by “optimization” before using the term.

Pretty sure the article is using optimization in the way you define it, but not, perhaps, the word “significant”.

I take Maya’s statement to imply that unnecessary optimizations do at least theoretically yield a performance increase, but one that is not “significant” – in other words, they would fail some sort of cost/benefit analysis in terms of minimal performance gained vs. lost code readability, portability, developer time, sanity, etc.

Optimization does correctly include using different compiler switches. As a specific quantifiable example, I have multiple STREAM binaries which only differ in the compiler options used. The base version is ‘-o3’ while the higher performing versions used more aggressive processor-specific optimization options. There’s a 30% performance difference from the base to the best performing /on my current desktop/. Optimizations can also include linking alternate libraries better suited to the specifics of the program’s code and datasets.

Unnecessary optimizations, which include Knuth’s ‘premature’ optimizations, come in many forms. As a specific (non-unique) example from my past, a person spent a few weeks tuning a part of a numerical code. While they achieved a local significant speedup–multiple times IIRC–the overall program performance was only improved by 1 or 2% because that code was just not consuming significant CPU cycles. Many numerical codes can be characterized by a Pareto distribution, with a few key math kernels consuming 80% of CPU cycles and the vast majority of the code in the 20%. This is what the OP was referring to when Valgrind was mentioned.

hindsight is always 20/20 :) . I can always look back at code I’ve written and, a lot of times, wonder why I did it that way when I could have done it ‘that way’ for better performance. Sometimes though performance is good ‘enough’ for the job at hand.

I’d add a chksum or CRC to the end of the message to better verify the data you sent is the data received to close the corrupted data possibility as well. A simple addition.

I’ve seen a file format that started out as just fields packed together and then for version 2.0 everything became 4-byte aligned for just this reason.

My thoughts about performance have evolved quite a bit. Used to be, you could count how many cycles an instruction would take, and you could be confident that fewer cycles was faster execution. And we meditated on eliminating copies. Especially compilers, very focused on keeping things in registers because they’re so much faster than stack. Avoid re-computation, avoid copying. Very straightforward.

These days, i’m convinced the only thing that matters is cache. If your problem is big enough that you can detect its performance, then it’s big enough that cache misses are its limiting factor. So even many iterations through a loop are free up until the loop is big enough to reference more than your cache’s worth of memory. So things like shrinking the code can reduce cache contention, which is a big reason compiled languages are faster than interpretted ones still (the interpretter is always using up cache space and de-referencing scattered pointers), but generally it’s the real data references forced by the algorithm and data structure that you’ve chosen that are the problem. At least in my life.

So the punchline is the only thing i look at anymore for performance improvements is the number of times through the loop and the overall amount of memory accessed by the loop. Other than that, if it’s recomputing something ten times inside of the loop because of a sloppy way i’ve specified it, i can fix that, and the performance will not improve even an iotum.

Largely, stack is as fast as registers (L1 cache is perfect). Reasonable-size memcpys are as fast as registers! Arithmetic, branching, conditional branching all take 0 time. But a “for(i=0;i<n;i++) use(array[i]);” memory visit is gonna eat you alive if n is bigger than cache. I’ve spent far too much of my life meditating on how to allocate strings to avoid copying, to find that the number of times through the loop is the only thing that matters, and even then it only matters if the loop is big. Even malloc() is cheap so long as the total volume of memory flowing through free->malloc->free->malloc is less than cache size!

Really a staggering way to look at things, from my perspective.

I have found this to be the case as well, but with a couple of caveats (or maybe just additional nuances) I’d add:

1) For programs where the working set exceeds cache it ends up being important to select data structures and craft to code to access them in a way that effectively hides the latency to L3 or DRAM since something like traversing a linked list gets very slow when chasing each pointer incurs a cold row open in DRAM, so modulo scheduling w/preferches and other software pipelining techniques can help.

2) Branches are cheap whem they’re predictable and local (or calls and returns to cached functions) but there is a limit to how effectively a deeply pipelined CPU can hide the cost of unpredictable branches. In situations where I’ve got a branch around a small block that’s mispredicted often I find that data flow based constructs can eliminate the branch at lower aggregate cost than leaving it in (e.g. always compute and store whatever conditional thing, but store it to either the real destination or a scribble buffer in the current stack frame — so long as the computation is cheaper than the misprediction penalty it generally wins). This way precious branch target buffer slots are saved for use when they help the most.

In general, though, it astounds me the degree to which people in general (even many developers) have a hard time grappling with the reality that, with today’s CPUs able to execute as many as 300 instructions in the time it takes to access main memory, the capabilities and behavior of cache and TLB are arguably the most vital thing to understand for any workload beyond tight number crunching loops with predictable access patterns.

To the author’s credit, it implicitly implies what “zero-copy” means but what was so scary important that there was no time to type a short sentence starting with “Zero-copy means…”? This is a chronic shortcoming of HaD articles.

“Shortcoming” means when you fail to do something you really should have done.

Did you seriously post a thing that boils down to “eww, girls?”

You have two choices. One is to take every term you don’t understand and put it into google. The other is to write a comment whining about how you weren’t spoonfed everything as if you were a baby who doesn’t know anything.

Only one of those choices is the right one.

Yeah, but he’s right too. Sometimes when you’re into something too deep, you forget to lay the groundwork.

Strong incel vibes here.

Strong stereotype arrogance vibe here.

Heh man what a thing, i guess i’m glad i finally clicked through to it.

It’s a little incel-pilled, mixing gender in with the spectrum. I think what they’re really getting at is how something changes as people engage with it for different reasons. If something becomes popular, people start engaging with it for social or economic reasons rather than merely “innate interest”, whatever that means. Another way to put it is that something can’t become very popular unless it can serve a social or economic role.

Hackaday has never really been on this spectrum because from the start it served a social and economic function. People participate in different roles for different reasons but fundamentally this blog is clickbait. And that’s not even really a criticism…simply, no one would bother if there wasn’t the promise of ad revenue of some sort.

Like this series of articles is a great example…i do projects not too different from this, and i do actually often write them up in huge meandering diaries. But i’m fundamentally writing a note to myself…even if i’ll never read it, i’m writing it because getting my thoughts into words is a key part of thinking to me. As a result, even the things i publish, i don’t publish in a form that anyone would want to click on. So on the one hand i can condescend that the writer here isn’t the same kind of programmer i am, isn’t having a particular interesting project, and isn’t delivering the most interesting insights. But on the other hand, they’re doing something i absolutely do not do, writing for a larger audience.

That’s fundamentally what this blog is. It’s trying to be a little bit popular. I can participate and bring my own energy to it but it isn’t being polluted by its popular appeal, by the intrusion of clickbait farmers and so on. That’s the thing it was.

And i’m bringing this up because it points to what i think is a significant flaw in the perspective of the comic. The two guys who originally started the hobby between them have lost nothing! The existence of this clickbaity forum doesn’t harm my hobby at all! If i want to sign off and do my own projects alone and out of the limelight, i can. If the dudes in the comic want to play their game with just eachother, they can. The only thing they’ve lost is actually something they’ve gained: they found out it was more fun to play the game with more people and now they’re lamenting the more people. The flaw, the contradiction, is in themselves…wanting more people but resenting that the game serves a social function now.

I tell you, i’m here largely because my time is carved up in ways that i have an overabundance of 5 minutes here and then and a complete starvation of uninterrupted project time. That’s not hackaday’s fault and i think it’s important to recognize that.

If you’re targeting the newest C++ versions, string_view is a good alternative to passing around a char* and a size. It can also do bound checking if you use .at(). You can create a string_view from a char* buffer and it is zero copy. span<> is also useful for the same purpose when your array is not an array of char.

I agree that memcpy is just too useful and fast that it’s worth using also in C++ code, and the compiler can understand what you’re trying to do and replace it with optimized code when copying small buffers.

As for unaligned accesses, ARM is getting better. Cortex M microcontrollers can do unaligned accesses. It’s the old ARM cores, and MIPS, that don’t support it.

Move semantics and unique_ptr are generally better ways of doing things like this in modern C++, and of course more modern languages like rust are built from the ground up with zerocopy ideals in mind. For that matter even pass-by-reference languages like Python and Java are going to be pretty okay about this aspect.

As long as you’re passing around the same string unchanged you’re right. Often, when parsing, you’re going to pass around substrings, and that’s where string_view wins in terms of zero copy behavior.

Most Cortex-M cores can do unaligned accesses. I had a Cortex-M0 (an RP2040!) choke on this very thing recently, which was a source of some confusion and then amusement.

I code in Python. What’s this optimisation thing everyone is talking about?