Like many of you, I have a hard time getting rid of stuff. I’ve got boxes and boxes of weirdo bits and bobs, and piles of devices that I’ll eventually get around to stripping down into even more bits and bobs. Despite regular purges — I try to bring a car-load of crap treasure to local hackerspaces and meetups at least a couple times a year — the pile only continues to grow.

But the problem isn’t limited to hardware components. There’s all sorts of things that the logical part of me understands I’ll almost certainly never need, and yet I can’t bring myself to dispose of. One of those things just so happens to be documents. Anything printed is fair game. Could be the notes from my last appointment with the doctor, or fliers for events I attended years ago. Doesn’t matter, the stacks keep building up until I end up cramming it all into a box and start the whole process starts over again.

I’ve largely convinced myself that the perennial accumulation of electronic bric-à-brac is an occupational hazard, and have come to terms with it. But I think there’s a good chance of moving the needle on the document situation, and if that involves a bit of high-tech overengineering, even better. As such, I’ve spent the last couple of weeks investigating digitizing the documents that have information worth retaining so that the originals can be sent along to Valhalla in my fire pit.

The following represents some of my observations thus far, in the hopes that others going down a similar path may find them useful. But what I’m really interested in is hearing from the Hackaday community. Surely I’m not the only one trying to save some storage space by turn piles of papers into ones and zeros.

Take a Picture, It’ll Last Longer

Obviously, the first step in digitizing physical documents is image capture. The most obvious way to accomplish this is to simply use a flatbed scanner, and in some cases, there’s a solid argument to be made that it’s the best approach. Indeed, many of the documents that I’ve already filed away digitally were created this way. But it’s a tedious enough process that you may want to consider alternative methods.

Obviously, the first step in digitizing physical documents is image capture. The most obvious way to accomplish this is to simply use a flatbed scanner, and in some cases, there’s a solid argument to be made that it’s the best approach. Indeed, many of the documents that I’ve already filed away digitally were created this way. But it’s a tedious enough process that you may want to consider alternative methods.

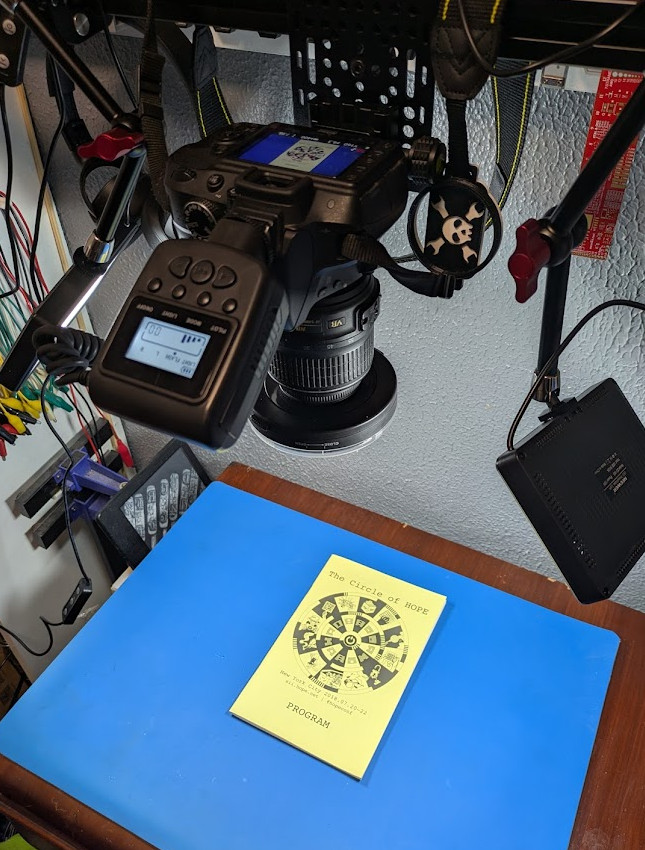

If you’ve got a decent camera, you can get a couple of lights and put together a nice overhead photography rig without spending too much money. Put your document down under the camera, snap a picture, and keep it moving.

Imaging doesn’t get any faster than taking a picture, and so long as you’re not using some point and shoot from the early 2000s, the resolution should be more than sufficient. This method is particularly appealing if you’re planning on digitizing books or anything else that can’t be laid perfectly flat on a scanner.

The major downside with this approach is the setup itself. It’s one thing if you’re digitizing documents and books on a daily basis, but for occasional use, putting something like this together is a big ask. A flatbed scanner certainly takes up a lot less room, and you don’t have to worry about getting the lighting right, mounting the camera, and so on.

Casting Some Magick

Whether you used a scanner or a camera, once you have the image of your document, you’ve technically digitized it. Congratulations, you’re now an amateur archivist.

If you’re looking to keep things simple, you could stop here. Stash the files someplace and be done with it. But depending on the type of content you’re working with and what your goals are, there’s a good chance you’ll want to touch up the images a bit. Luckily for us, the incredible ImageMagick project has many of the functions we need built-in, from cropping and resizing, all the way to image enhancement.

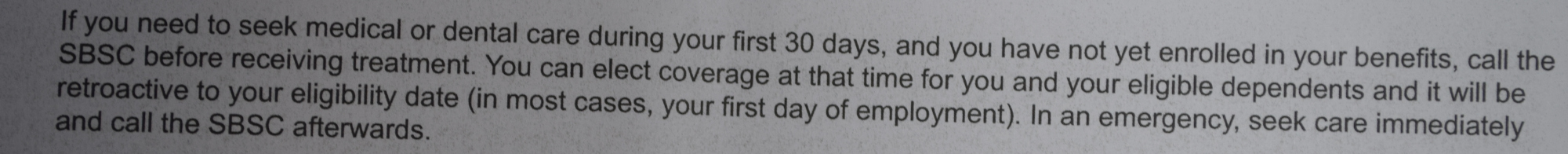

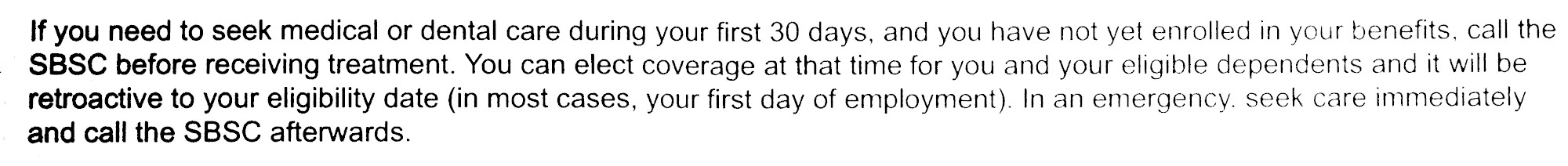

Consider the image below. It’s clear enough to read, but the text is rotated and the lighting isn’t consistent across the entire page.

We can fix both issues with a simple ImageMagick command via the convert tool:

convert input.png -deskew 30% -threshold 25% output.png

We won’t get too bogged down in the details, the ImageMagick documentation can break it all down better than I can. The short version is that we’re telling it to straighten out the image and convert it into pure black and white. The result looks like this:

The values can be tweaked a bit to refine the result, and as you might imagine there are many other ImageMagick functions that could potentially be brought in to clean up the result. Things do get more complicated if you’re working with something more complex than plain text, but you get the general idea.

This sort of post-processing is especially important if you plan on running the images through any sort of optical character recognition (OCR) to capture the actual text of the document. That first image might be perfectly legible to our human eyeballs. You might even prefer it over the stark look of the processed image, but tools like tesseract have a hell of a time picking the text out when the background isn’t uniform.

There’s an App For That

The process described here certainly isn’t for everyone, and that’s fine. If you’re not looking to invest the sort of time and effort it would take to make this work, there’s fortunately a far more approachable solution available. In fact, it might already be in your pocket.

The process described here certainly isn’t for everyone, and that’s fine. If you’re not looking to invest the sort of time and effort it would take to make this work, there’s fortunately a far more approachable solution available. In fact, it might already be in your pocket.

The Google Drive mobile application offers a very impressive document scanning mode that essentially automates everything above. If you give it access to your device’s camera, it will automagically detect documents in the field of view, find their edges, compensate for angle and rotation to straighten out the image, and even run it through filters to make the text pop. It’s fast, works reasonably well, and is exceptionally handy for cranking out multi-page PDFs.

The downside is that you’ve got relatively little control over the process, and being a product of Google, there’s the usual concerns over what they may be doing with the information that’s passing through the system. For these reasons it’s not something I would personally recommend for any private information, and its automatic nature the lack of fine-grained control means it may not be a great choice if your needs venture too far from the beaten path.

Still, the speed and ease of use it offers is admittedly very attractive.

Open to Suggestions

I’d love to hear the community’s thoughts on digitization, whether it’s hardware or software related. There’s surely some slick projects out there that aid in creating bespoke digital libraries, and there’s plenty of areas where real-world experience can help streamline and improve the overall process. For example, what’s your file naming convention look like?

Hackaday readers are rarely shy about sharing their opinions, so let’s hear them.

One thing I continuously struggle with is handwritten courses and documents. There’s some good information in most courses I have had that’s hard to come by anywhere else, oftentimes because the teacher was knowledgeable enough to gather it and synthetize it in the first place. However, I have noticed that the ink in some of these notebooks is already starting to fade, although they were written only seven years ago. They are still useful to me today, and will be in the future, so I need to archive them.

I have a very irregular handwritting and no automatic tool has been able to help me in the goal of digitizing them (amongst others, I’ve tried Kraken and a lot of OCR datasets). My only option so far is to type them by hand, but it’s incredibly time consuming.

OCR works really well on typed documents, recent or old, and Kraken is a great tool. But I am quite baffled at the complete lack of any way to digitize handwritten documents from the modern era – most datasets being fit only for 17th and 18th century in Europe (to digitize letters/communal records). Moreover, the fact that each person has their own way of writing each letter of each letter – and my way is rather erratic, although I can decipher myself ok – makes the application of OCR way more difficult. And last but not least… All of my notebooks are checkered in blue, and I use blue ink, which confuses OCR completely and only produces gibberish at best.

You might be better off reading the information aloud into transcription software, then manually cleaning up the output, unless there are a lot of diagrams and such. Or, if it’s very valuable, you could hire a transcriptionist.

I have a Canon DR-M160 I got for ten bucks. Rapid feed duplex document scanner. Feeds it straight into paperless-ngx. Look it up, its awesome, can pull docs from emails also.

Digitizing is not archiving.

Digitizing is only part of the task. That’s just kicking the can a tiny bit down the road. You still have a pile of unfindable, unsearchable stuff.

So how to make that pile of unsorted, inscrutable bits and bytes useful?

Rather than simply digitizing, I think a more useful thing to know is what do do with the digitized output? How do you make it searchable? How do you make it useful?

Photo people have kind-of got a solution with manually-entered image tags. But there must be a better way, especially with OCR and machine recognition of images.

Anybody got suggestions or best practices on how to file, sort, and search the mess of files generated?

Some use AI (yes that).

As proposed one post higher up: paperless-ngx

Don’t use it myself at the moment, but I intend to, I heard good things from people using it.

That’s literally what the end of the post asks about and is looking for input on.

Like Matt, but built into the printer. Even has the feature of conversion and sending to a particular source. Hardest part is prepping the papers so it feeds cleanly with little problem.

On a related note: Has anybody got any experience to share about the reMarkable tablet https://remarkable.com/ ?

It looks really well thought out, with tight integration with filing and searching tools, but a bit out of the “impulse buy” range.

Beware the digital document trap: Nobody may be able to read your digital storage medium in the future.

I’m going through my late father’s papers. I found a lot if interesting stuff, including his notebook from the Navy during World War II. I also found a bunch of 5.25″ floppies that he wrote using WordPerfect.

I can read the papers, but the WordPerfect disks are basically worthless.

Remember: Paper is the ONLY medium that is guaranteed to be machine-readable in 50 years.

If they aren’t completely bit-rotted, there are plenty of ways to get the WP files off of those floppies and converted to newer file formats.

Paper wise, nobody will care either after we are gone. So personally, I file what needs to be filed (paper) for my use and don’t worry about the future. Filing it keeps it ‘neat’. Also what I want to save in the electronic world, I keep it spinning (with backups stored internal and external). That way the storage media is always up to date and you don’t have to worry about supporting 8″ floppies (for example) forever. And in 50 years, 100 years, … no one is going to care.

I seem to recall downloading from WordPerfect the suite which had a 30 day eval. Was able to read and then write to another format.

That and they have sales on it if one wants that authentic feel.

I’ve seen this argument plenty of times, but I don’t buy it. I promise you, there’s a way to read that data on a modern machine, even if it means emulating an old OS and running WP.

But even that is an edge case. The major file formats, like JPG/PNG/PDF aren’t going anywhere and I can still open 30 year old files as if they were created yesterday.

If anything, the lesson should be to not use proprietary formats that only exist because some company is propping it up.

man, i’m pretty confident i could reverse engineer word perfect by hand without any prior knowledge, at least well enough to extract the prose. i have gone down that road before, for much more obscure formats than wordperfect. i’m just saying, don’t give up. all else fails, there’s emulators for every classic PC or mac program from 1980 to today.

First, i think it’s important to recognize that a lot of things can be thrown out! And the things worth preserving are not really that voluminous. 90% of books i buy go into the donation pile after 1 read. And paper-ink does age pretty severely but even thermal copyright paper is usually (but not always) readable for decades without climate control in a humid inland continental climate. And the things i keep, anyways, are easy enough to index hierarchically. Like if i want to find my notes from a class i took in the 1900s, ~/text/university/1999-fall/C211 gets me there fine.

Overhead scanners are often available at libraries. The details will decide whether it actually works for you. They usually install software that will give aspect correction (like for the pages of a book that are curved towards the spine) and searchable PDF-style OCR. That software’s real magic feature is that the library staff member who tells you where it is probably can show you how to use it too.

And a note on imagemagick…real love/hate relationship. The biggest frustration is that for output PDFs, there is a really intractable relationship between different conceptualizations of # pixels, # inches, pixels per inch, and aspect ratio, which are all tracked separately for different formats. I spent many hours trying to get a bulletproof solution to that problem. What i found is: pdflatex with \usepackage{graphicx}. Absolutely everything about its \includegraphics works exactly how you’d expect. Just amazing.

“First, i think it’s important to recognize that a lot of things can be thrown out! And the things worth preserving are not really that voluminous.” Right on the button. As you get older you notice the things that get ‘used’ and those items or notes or books or … that haven’t been touched in 20 years. As an example, Just recently I noted we had shelves of magazines that I realized I’d never look at again (thought I would, but…) . Also a bunch of books that I would never re-read. College notes, books never opened or read again … all donated/deep six’ed. Interesting the things you ‘think’ you would need as references or re-read… and never look at again!

I have an old Fuji ScanSnap document scanner that a friend gave me when it got obsoleted by MacOS going 64 bit. I have an old Windows 10 laptop (airgapped of course) that I use with it, since it’s not compatible with Windows 11 either. It can auto feed 10 or so pages and you just push a button to scan.

Fortunately I squirreled away copies of the driver, since Fuji sold the IP to Ricoh who has memory-holed the drivers, taking “not supported” to a whole new level. It takes real effort to keep these perfectly working things out of the e-waste pile!