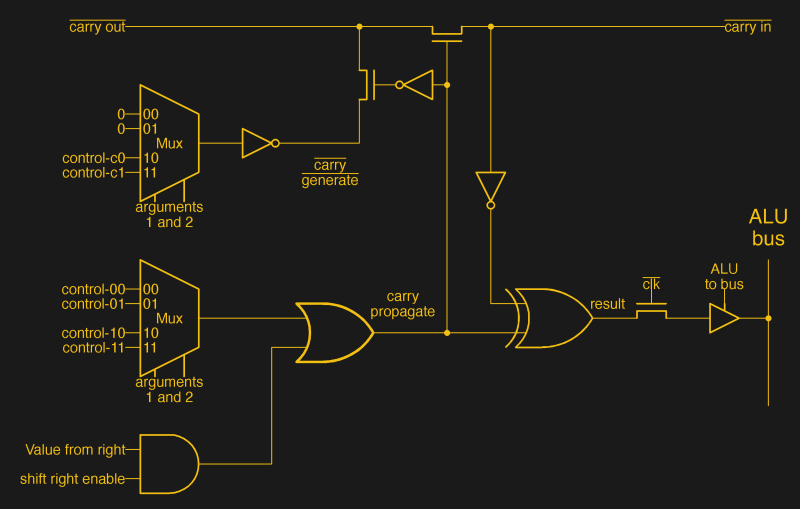

In the 1970s CPUs still had wildly different approaches to basic features, with the Intel 8086 being one of them. Whereas the 6502 used separate circuits for operations, and the Intel 8085 a clump of reconfigurable gates, the 8086 uses microcode that configures the ALU along with two lookup tables. This complexity is one of the reasons why the Intel 8086 is so unique, with [Ken Shirriff] taking an in-depth look at its workings on a functional and die-level.

These lookup tables are used for the ALU configuration – as in the above schematic – making for a very flexible but also complex system, where the same microcode can be used by multiple instructions. This is effectively the very definition of a CISC-style processor, a legacy that the x86 ISA would carry with it even if the x86 CPUs today are internally more RISC-like. Decoding a single instruction and having it cascade into any of a variety of microcodes and control signals is very powerful, but comes with many trade-offs.

Of course, as semiconductor technology improved, along with design technologies, many of these trade-offs and disadvantages became less relevant. [Ken] also raises the interesting point that much of this ALU control technology is similar to that used in modern-day FPGAs, with their own reconfigurable logic using LUTs that allow for on-the-fly reconfiguration.

Modern x64 CPUs are pretty much ARM-like because it offers greater performance in daily applications and games.

I don’t get what you mean? X86 is still very CISC and the overheads of being CISC will always be present. CISC doesn’t mean slow nor power inefficient, especially today where inefficiencies are mostly non-architectural.

They’re RISC-CISC hybrids, I think. RISC core with a CISC front-end, in layman’s terms.

And this combo isn’t so bad, actually.

CISC instructions get broken down into smaller instructions which can be put into several pipelines, for parallel processing.

The really complex thing is cache coherency and predictions about which instruction or code sequence might be needed next.

A cache flush by a cache miss causes big performances penalty, maybe.

That’s why self-modifying code fell out of favor. It didn’t work efficiently on 486 and higher CPUs anymore.

The last true x86 CISC designs were the 286/386, perhaps.

Though 386 systems often had external cache on motherboards by the 90s,

which suffered by cache misses by self-modifying code.

And 8086/8088 did address calculation in the ALU, which also was time consuming.

By contrast, the much more sophisticated 286 had a dedicated circuit for such calculations (it also had a real MMU by the way).

The 8018x and NEC V20/V30 maybe, as well, but I’m not sure right now.

All in all, the 8086 was “okay” though. Laughing about it wasn’t necessary. By mid-70s standards it was fairly descent, actually.

The crippled 8088 derivative was much worse (performance cut in half, behind 6510).

Still, I think the NEC V30 was the better overall design, though.

It compared to 8086 like the Z80 did to the ancient 8080.

If needed, the NEC also could “emulate” (mimic) 8080 instruction handling through a register renaming technique,

making it more of a true 8080 descendant than the original 8086, even.

Paradoxically, that means that the NEC V30 is processing things at a level closer to the “bare metal” than the 8086 (more native).

Especially if it does rely less on microcode (seems to be the case).

I know, it’s a bit of an unpopular opinion, maybe. 🙁

There’s more to it, maybe.

The x64 (or x64-2) architecture takes certain x86 features as given.

Such as the SIMD instructions MMX, SSE and so on. Which used to be optional extensions on x86.

By contrast, pure x86 applications did merely use 386/486 instructions most of time.

Many everyday Win32 applications such as WinAmp or Irfanview thus will keep running happily on a 486 PC with Windows 9x.

The Win64 builds are already utilizing extra instructions because of compiler defaults used for x64.

Another thing is high-level approach on OSes such as macOS or Windows.

Normal GUI-based applications don’t to make much calculations,

but make calls to the operating system, to libraries.

Which then in turn do the hard work or pass things further to other libraries.

So it’s not very performance intensive to emulate a Win32 x86 copy of, say, Irfanview on an ARM-based Windows.

Because the Windows DLLs used by the application are already available in native code in most cases (some applications ship their own DLLs which are x86 then ofc).

The x86 GUI application going to be run thus merely needs to adapt to interoperate with ARM code.

The solution can be interpreted, emulated or dynamicly-recompiled.

There are exceptions, of course. Especially when it comes to the thinking part.

3D games with a complicated engine must are a challenge, for example,

because lots of processing power is wasted on the CPU emulation.

By contrast, games relying on the operating system’s engine might see little to no performance penalty.

I’m thinking of older Direct3D Retained-Mode titles, which use the built-in 3D engine being part of DirectX.

So if the ARM-based Windows still ships with native DirectX files for the old API, then there’s little overhead.

Not that it matters, considering that Pentium 133 level of performance is good enough for playing such titles at the end of day.

PS: In the 90s, there had been RISC platforms already (besides ARM). MIPS, Alpha PC, Power PC..

Windows NT ran on all of them and it had an 286/486 CPU emulator for NTVDM and Windows on Windows.

So DOS and Windows 3.x applications ran in emulation back then, with performance being accepable.

Optional products such as FX!32 (Alpha) or SoftWindows (Power PC) allowed running x86 Win32 applications on such RISC Workstations.