Birds are pretty amazing creatures, and one of the most amazing things about them and their non-avian predecessors are feathers. Engineers and scientists are finding inspiration from them in surprising ways.

The light weight and high strength of feathers has inspired those who look to soar the skies, dating back at least as far as Ancient Greece, but the multifunctional nature of these marvels has led to advancements in photonics, thermal regulation, and acoustics. The water repellency of feathers has also led to interesting new applications in both food safety and water desalination beyond the obvious water repellent clothing.

Sebastian Hendrickx-Rodriguez, the lead researcher on a new paper about the structure of bird feathers states, “Our first instinct as engineers is often to change the material chemistry,” but feathers are made in thousands of varieties to achieve different advantageous outcomes from a single material, keratin. Being biological in nature also means feathers have a degree of self repair that human-made materials can only dream of. For now, some researchers are building biohybrid devices with real bird feathers, but as we continue our march toward manufacturing at smaller and smaller scales, perhaps our robots will sprout wings of their own. Evolution has a several billion year head start, so we may need to be a little patient with researchers.

Some birds really don’t appreciate Big Brother any more than we do. If you’re looking for some feathery inspiration for your next flying machine, how about covert feathers. And we’d be remiss not to look back at the Take Flight With Feather Contest that focused on the Adafruit board with the same name.

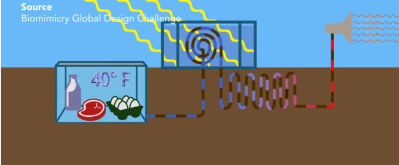

The aim of this challenge is to transform the global food system using sustainable approaches that emulate natural process. Entries must address a problem somewhere in the food supply chain, a term that could apply to anything from soil modification to crop optimization to harvest and storage technologies. Indeed, the 2015 winner in the Student category was for a

The aim of this challenge is to transform the global food system using sustainable approaches that emulate natural process. Entries must address a problem somewhere in the food supply chain, a term that could apply to anything from soil modification to crop optimization to harvest and storage technologies. Indeed, the 2015 winner in the Student category was for a