[Ronnie] recently posted a new chapter in his adventures in malware deconstruction. This time the culprit was an infected Excel spreadsheet file. The .xls file was attached to a phishing email claiming to be related to a tax rebate. With tax season in full swing, this type of phishing message would be likely to be opened by an inexperienced user.

[Ronnie] saved the file to a virtual machine to prevent his real workstation from getting infected. He then opened it up in Excel and noticed that it immediately attempted to run macros. A macro is essentially visual basic scripting that runs inside of the spreadsheet file. You can use it for simple automation, cell formatting, or do even more complicated tasks like reach out to external websites and pull information. This malware focused on the latter.

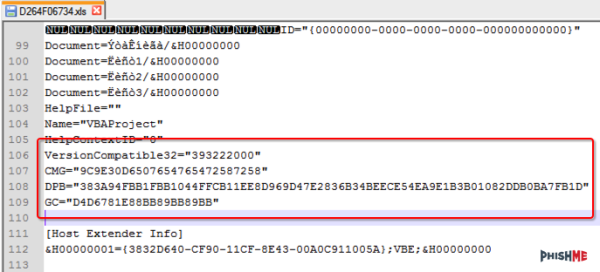

[Ronnie] used the alt + F11 shortcut to view the macros. Unfortunately the attackers had password protected them. [Ronnie] wouldn’t be able to view the macro code without knowing the password. Luckily, he learned of a surprisingly simple trick to completely bypass the macro password. He opened up the .xls file in Notepad++ and located three keys; CMG, DPB, and G. [Ronnie] then created and saved a new blank .xls document and password protected the macros with his own password. He opened up this new file in Notepad++ as well, and located those same three keys. He copied the keys from the new file into the old one, and saved the old file. This effectively changed the password of the malware file to the new one he had set for his new file. This is a nifty trick that apparently only works on the older .xls formats, not the newer .xlsx format.

After loading the macros, [Ronnie] quickly noticed that most of the code was obfuscated to make it difficult to analyze. There were, however, three named modules that reference possible sandbox evasion techniques. The malware first invokes these functions to detect the presence of a virtual machine or other type of sandbox. If it detects nothing, then the rest of the malware program is decoded and executed. [Ronnie] removed these checks and then executed the macro to verify that his change had worked.

The next step was to try to view the decoded instructions. The decoded gibberish was saved to a variable. The simplest way for [Ronnie] to view the contents of the variable was to have the program create a pop-up box that displayed the contents of that variable. After making this change and running the program again, he was able to see exactly what the malware was doing. The code actually invoked Powershell, downloaded a file from the Internet, and then extracted and executed that file. In the full write-up, [Ronnie] goes even further by downloading and analyzing the executable.